This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

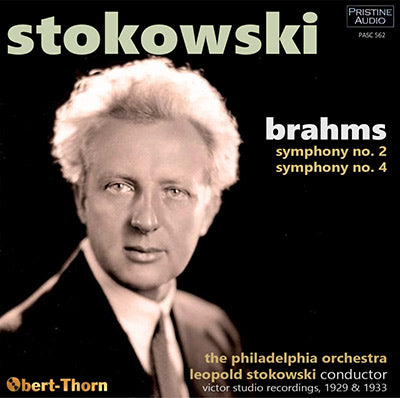

This release completes the reissue of the Brahms Symphony cycle by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra, begun with their 1927 recording of the First Symphony (Pristine PASC 500) and continued with the Third Symphony from the following year (PASC 540). The Second was next to be recorded, followed by the Fourth; but both proved problematic, requiring additional takes ranging from a single side to an entire remake.

After recording the Second Symphony over two consecutive days in April,

1929, Stokowski decided to remake Side 6, the second side of the second

movement, eleven months later. Apparently, neither producer nor conductor

remembered where the original take began, and the remake started twelve

measures late, leaving out nearly a minute of music. Incredibly, no one

noticed the missing bars before the recording was released. When the gap

was discovered, a take from the earlier sessions was quickly substituted. The remake can be heard as a bonus track in all downloads as well as the free MP3 download package offered with all online CD purchases, while the take from the original sessions is presented within this release.

In his book, Conducting the Brahms Symphonies, critic Christopher Dyment had a mixed verdict regarding the performance, saying that while it contains “a Classically balanced first movement,” it is “succeeded by an overripe Adagio and two further movements markedly lacking in rhythmic lift and forward impetus,” a charge similar to that levied against the last movement of Stokowski’s 1928 Brahms Third. Dyment goes on to note that Stokowski later revised his approach to the last three movements: “[T]he 1950 New York Philharmonic [issued on Pristine PASC 215] and Bavarian Radio broadcasts replace the early, somewhat turgid style with something altogether fleeter and, in the finale, with a drive that tests both orchestras to their limits.”

More successful as an interpretation was Stokowski’s approach to the Brahms Fourth; but here, he was undercut by substandard recorded sound. During the early years of the Depression, Victor recorded the Philadelphia Orchestra in a Camden, New Jersey church converted to a studio in order to avoid having to rent the Academy of Music. Reduced forces were used, cutting the strings from 18-18-12-12-10 to 6-6-4-5-3. By 1934, sessions were held in the larger area of the church’s nave, listed on the ledgers as “Church Studio No. 2”; but in the period from 1931 through 1933, most were made in what orchestra harpist Edna Phillips’ described to her biographer as “a Sunday school room on the second floor,” devoid of reverberation (which has been added in this transfer).

Added to this is another anomaly. The Fourth Symphony had initially been recorded in April, 1931 on 14 10-inch sides. Album number M-108 was allocated to this version, but it was apparently never released. (Transfers of this version from test pressings have been issued on LP and CD.) Nearly two years later, the present recording was made in the same venue, with similarly reduced forces. While Stokowski would go on to re-record the Second Symphony only once in 1977, at the very end of his career, he made two further recordings of the Fourth, one with the All-American Youth Orchestra in 1940, and a second with the New Philharmonia, following its appearance in his final London concert in 1974.

Mark Obert-Thorn

STOKOWSKI conducts BRAHMS

Symphony No. 2

Symphony No. 4

BRAHMS Symphony No. 2

in D major, Op. 73

1. 1st Mvt. - Allegro non troppo (14:38)

2. 2nd Mvt. - Adagio non troppo (10:34)

3. 3rd Mvt. - Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino) (6:12)

4. 4th Mvt. - Allegro con spirito (9:58)

Recorded 29-30 April 1929 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CVE 47951-3, 47952-2, 47953-2, 47954-2, 47955-3, 47956-2

47957-2, 47959-1, 47960-2, 47961-2, 47962-2 & 47963-4

First issued on Victor 7277/82 in album M-82

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 4

in E minor, Op. 98

5. 1st Mvt. - Allegro non troppo (11:19)

6. 2nd Mvt. - Andante moderato (11:39)

7. 3rd Mvt. - Allegro giocoso (6:03)

8. 4th Mvt. - Allegro energico e passionato (9:31)

Recorded 4 March and 29 April 1933 in Church Studio No. 1, Camden

Matrix nos.: CS 75162-1, 75163-1, 75165-1, 75167-2, 75168-1, 75169-1,

75171-1, 75172-1, 75174-2 & 75175-2

First issued on Victor 7825/9 in album M-185

included on downloads for this release

The Philadelphia Orchestra

conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Total duration: 79:54

Fanfare magazine review

The one challenge I had with this review is that every time I sat down to write it, I first wanted to hear the disc over again! It was always time well spent.

This release marks the conclusion of Pristine Audio’s survey of the Brahms Four Symphonies, recorded for RCA by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra between 1927 and 1933, here in restorations by Mark Obert-Thorn. My Fanfare colleague Raymond Tuttle reviewed the initial two Pristine Audio releases, the first comprising the 1927 Brahms First, coupled with various shorter orchestral works (Issue 41:2, Nov/Dec 2017). The second disc, reviewed by Tuttle in the March/April 2019 issue (42:4), features the 1928 Brahms 3, and 1927 Dvořák “New World” Symphony. Tuttle praised both the performances and Obert-Thorn’s restorations, which he marginally preferred to Ward Marston’s remastering of the Stokie/Philadelphia Brahms cycle for a 1994 Biddulph two-disc set. I am in accord on both accounts, with more detail now to follow. During the course of his conducting career which spanned almost 70 years, Stokowski frequently programmed the Brahms symphonies. Stokie also made numerous recordings of the works, the 1927–33 cycle with Philadelphia being his first for each symphony. It’s worth noting, too, that Stokowski was born six years after the first performance of the Brahms First Symphony, and he was three years old when the last of the Brahms symphonies premiered in 1885. It might be a stretch to say the Brahms symphonies were “contemporary music” when Stokowski first conducted them, but they also hadn’t quite achieved warhorse status. And without question, the Stokie-Philadelphia Brahms cycle provides a treasured window into a bygone era of Brahms interpretation.

By the time Stokowski and Philadelphia recorded the Brahms 2 in 1929, the second decade of his tenure was drawing to its conclusion. This was a period when the conductor and orchestra were at their zeniths, capable of performances that were electrifying both for razor-sharp execution, and for a sonic canvas stunning in terms of richness, beauty, and power. If I were to nominate one recording from that era to showcase the unique qualities of the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski, it would probably be their hair-raising 1926–27 Wagner Rienzi Overture. But I think the 1929 Brahms Second is a worthy souvenir as well. It is true that Stokowski could be a willful conductor in terms of interpretation, one not beyond altering the score to suit his preferences. In the finale of the Brahms Second, Stokowski extends the sustained trombone and tuba passage through the start of the penultimate measure (the composer ends it a measure earlier). Stokowski also elicits beautiful string portamentos and frequent use of rubato that rarely occur in modern performance, much to our loss, in my opinion. But I think the glorious, marvelously blended sound of Stokie’s Philadelphians would be welcome in any age. In his liner notes for the Pristine Audio release, Obert-Thorn quotes Christopher Dyment’s comments from his book Conducting the Brahms Symphonies. Dyment characterizes the opening movement as “Classically balanced,” but the remainder as “markedly lacking in rhythmic lift and forward impetus.” It is true that Stokowski favors measured tempos and emphasizes the darker colors of Brahms’s orchestration. But to my ears, that represents an approach that is both different and intriguing, rather than inferior. Regardless of whether one agrees with Stokowski’s interpretive choices, the beauty and incisiveness of the Philadelphia Orchestra’s playing is beyond reproach. The 1929 recording, made in the Philadelphia Academy of Music, wears its years remarkably well, especially in Mark Obert-Thorn’s restoration that reveals considerable detail, dynamic range, and tonal richness.

When Stokowski and Philadelphia recorded the Brahms 4 in 1933, austerity measures necessitated by the Great Depression were in place. The complement of strings was reduced by about 2/3, and the recording venue was shifted from the Academy of Music to a church in Camden, NJ that had a notably dry acoustic. Stokowski compensated by employing a greater number of microphones, placed closer to the performers. This, coupled with Stokowski’s genius at eliciting a rich orchestral sound, resulted in a recording that perhaps is not the sonic equal of the Second, but still more than holds its own. And it is a marvelous performance. Here, the tempos are fleeter overall than in the Brahms Second, in a rendition that never lacks for momentum. Once again, lovely application of rubato and portamento is a prominent, welcome feature. For the most part, tempo fluctuations are applied in a restrained manner, one exception being the helter-skelter dash to the finish in the opening movement’s coda. The finale of the Brahms Four is a stunning series of variations over a ground bass Brahms incorporated from the final movement of Bach’s Cantata No. 150. As you might imagine, such music was tailor-made for Stokowski, a man who fashioned numerous brilliant orchestral arrangements of Bach works. The performance by Stokowski and Philadelphia of the finale is brimming with momentum and dramatic intensity, right to the shattering closing bars.

In comparing Marston’s restoration for Biddulph with Obert-Thorn’s for Pristine Audio, I found the latter to have slightly greater presence and dynamic range, with a corresponding (though not distracting) increase in disc surface noise. If you already own the Biddulph set, I don’t think the Pristine Audio is a must. But as the Biddulph is out of print, and the Pristine Audio is an excellent restoration, I recommend the new release without reservation. In fact, the one challenge I had with this review is that every time I sat down to write it, I first wanted to hear the disc over again! It was always time well spent.

Ken Meltzer