This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Maurice Ravel and Pierre Monteux: Architects of French Sound

Maurice Ravel and Pierre Monteux were born in 1875, and though their lives rarely intersected intimately, they were bound by a shared devotion to precision, poise, and the search for orchestral colour without sentimentality. While Ravel was famously private and exacting, Monteux was genial and unshakeable—but the musical results they achieved together, especially through Monteux’s interpretations, reveal a profound kinship.

Monteux was not part of Ravel’s close artistic circle—Ravel gravitated more toward pianists like Ricardo Viñes or the conductor-designer Alexis Roland-Manuel—but Monteux was one of the few conductors Ravel respected. Their most famous direct collaboration came in 1912, when Monteux conducted the premiere of Daphnis et Chloé with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. It was a challenging production: the choreography by Michel Fokine was demanding, and the massive orchestral forces—plus chorus—presented formidable difficulties. Yet Monteux’s steady hand brought coherence to the performance. While it was eclipsed at the time by the scandal of Nijinsky’s dancing and Stravinsky’s looming Sacre, Daphnis soon emerged as one of Ravel’s masterpieces.

Decades later, Monteux would return to this vast score in one of the crowning achievements of his recorded legacy. In 1959, with the London Symphony Orchestra and chorus, Monteux recorded the complete Daphnis et Chloé for Decca—a landmark version. At 84 years old, Monteux led the orchestra with the energy and precision of a man half his age. The recording captures every shimmer and swell of Ravel’s writing with breathtaking transparency. The famous "Lever du jour" (Daybreak) is rendered not as a lush wash, but as a delicately evolving light—each instrument clear, perfectly balanced, never overindulged.

Critics and collectors often return to this version as the most idiomatic of all. Monteux, who had premiered the work nearly half a century earlier, understood that its brilliance lies not in bombast but in control. There is nothing overripe in his interpretation—just luminous textures and rhythmic poise. It's Ravel as Ravel might have heard it in his mind.

Monteux had a deep affinity for the London Symphony Orchestra, and in the early 1960s their partnership entered a golden phase. In 1961, Monteux recorded two more Ravel gems with the LSO: the Pavane pour une infante défunte and Rapsodie Espagnole. Both are miniature masterclasses in restraint and colour.

The Pavane, often subjected to syrupy interpretations, emerges in Monteux’s hands as a dignified lament. His tempo is deliberate but never dragging. The famous horn solo is noble, not mawkish, and the phrasing throughout is shaped with understated elegance. Monteux once said, “Ravel must never be sentimentalised—it ruins the structure.” This Pavane proves the point: it glows softly, like a faded photograph, dignified and deeply moving precisely because it refuses to plead.

His Rapsodie Espagnole, recorded in the same sessions, is a model of orchestral discipline and flair. Ravel’s evocation of Spain—filtered through French elegance—is handled with just the right balance of heat and cool. Monteux lets the rhythms speak naturally: the “Prélude à la nuit” is mysterious without being heavy; the “Feria” dances with taut energy. The LSO plays magnificently, responding to Monteux’s economical yet expressive gestures. As always, he avoids exaggeration. “You must trust Ravel’s pen,” he once told a student. “It already sings. You don’t need to shout.”

Monteux’s long-standing belief in Ravel’s music went beyond national pride. While he helped define the French orchestral tradition, he approached scores with a craftsman’s eye. Even as a centenarian in spirit—he signed a 25-year contract with the LSO at age 86—Monteux remained committed to clarity above all. His recorded Ravel offers no eccentricities, only the distilled essence of the music.

Though Ravel and Monteux were never close personally, their paths reflect a shared philosophy. Neither was a revolutionary in the flamboyant sense. Ravel constructed his works with classical discipline and sensual restraint; Monteux conducted them with the same values. Ravel distrusted flashy interpretation. Monteux disdained conductors who drew attention to themselves. “The conductor is not the composer,” he would say, “only the servant of the score.”

In that sense, Monteux may have served Ravel more faithfully than any other conductor of his generation. The 1959 Daphnis, the 1961 Pavane and Rapsodie—these recordings still stand as exemplars of how Ravel should sound: luminous, unsentimental, and exquisitely clear.

As Monteux once reflected, “If the music is perfect, you don’t polish it—you just let it shine.” In letting Ravel’s music shine, he helped preserve a sound-world that still feels utterly modern today.

1. RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte, M. 19 (6:44)

RAVEL Rapsodie espagnole, M. 54

2. 1. Prélude à la nuit (4:07)

3. 2. Malagueña (2:15)

4. 3. Habanera (2:36)

5. 4. Feria (6:27)

RAVEL Daphnis et Chloé, M. 57

Tableau I (Une prairie а la lisiére d'un bois sacré)

6. Introduction et danse religieuse (7:18)

7. Danse générale (2:43)

8. Danse grotesque de Dorcon (2:18)

9. Danse légère et gracieuse de Daphnis (2:23)

10. Danse de Lyceion (4:38)

11. Danse lente et mystérieuse des Nymphes (4:40)

Tableau II (Camp des pirates)

12. Introduction (2:55)

13. Danse guerrière (4:06)

14. Danse suppliante de Chloé (5:14)

Tableau III (Paysage du première 1er tableau, а la fin de la nuit)

15. Lever du jour (5:12)

16. Pantomime (Les amours de Pan et Syrinx) (5:29)

17. Danse générale (Bacchanale) (4:53)

Royal Opera House Chorus

London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Pierre Monteux

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

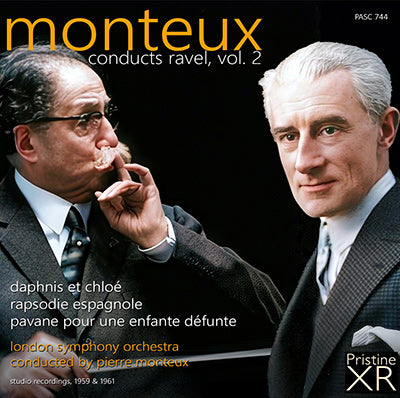

Cover artwork based on photographs of Pierre Monteux and Maurice Ravel

Tracks 1-5 recorded 11-13 November 1961

Producer: Erik Smith

Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Tracks 6-17 recorded 27-28 April, 1959

Producer: John Culshaw

Engineer: Alan Reeve

Recorded in stereo at Kingsway Hall, London

Total duration: 73:58