This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Contemporary live review

The circumstances under which this recording was made are worth retelling. Between November 1957 and August 1958 George Mendelssohn of Vox Records was negotiating with the London Symphony Orchestra for a series of studio recordings with Horenstein, to be synchronized with concert appearances featuring the same works. In June 1958, as a result of these discussions, the LSO engaged Horenstein for two concerts, a performance of Mahler 5 in Leeds on Nov. 1st and another appearance in London on Nov. 9th featuring works by Bartók, Prokofiev and Berlioz. However by the end of August 1958, after equivocating for months, Mendelssohn had already pulled out of both projects leaving the LSO, at that time in dire financial straits, with no recordings and stuck with two concerts they could not afford nor wanted to promote alone. Following Mendelssohn's exit, repertoire and soloists were rapidly changed for Horenstein's Nov. 9th concert, but the Mahler symphony was kept in the program for Nov. 1st after the BBC, on the initiative of Robert Simpson, stepped into the time slots previously reserved for Vox. Following five rehearsals, the first for strings only, Mahler 5 was recorded by the BBC at a single session during the afternoon of 30th October 1958 and documents the first-ever LSO performance of the work. The recording of what was essentially a dress-rehearsal was followed by the concert in Leeds two days later, the orchestra's first public performance of the symphony (not broadcast or recorded) that attracted an enthusiastic crowd and favorable reviews. “At the end”, a surprised Horenstein told Deryck Cooke, “the large audience acclaimed it as though it were some accepted masterpiece”, which at that time was clearly not the case.

Mendelssohn's withdrawal from the project exacerbated an already strained relationship with Horenstein who some months later categorically refused to work with him or with Vox Records ever again, but there was another player in this saga: Everest Records. In August 1958 Everest began making a series of commercial recordings with the LSO that initially featured Walter Susskind and Eugene Goossens conducting contemporary music. Then in September the LSO's manager John Cruft wrote to Everest with more repertoire and conductor suggestions including, among others, a recording of Mahler's Fifth with Rudolf Schwarz. In his letter Cruft did not mention Horenstein, already one of the LSO's regular guest conductors and about to tackle the Fifth (and later the Eighth) with the orchestra. Whether this omission was accidental or deliberate is unknown, but, according to the LSO's official discography, Everest's recording of the Fifth Symphony with Schwarz, the orchestra's first commercial recording of any music by Mahler, was made on 10-11 Nov. 1958, just ten days after Horenstein rehearsed, recorded and performed it with the same orchestra in London and Leeds! Free from his obligations to Vox Records by the end of August 1958, there were no contractual issues nor any prior engagements to prevent him from accepting the Everest recording job had it been offered. Why the LSO and Everest chose Schwarz for their recording, fine effort though it is, remains a mystery, to be classified as another example of Horenstein's unfortunate career as a recording artist. Published here for the first time in any form and the first of three preserved recordings of Mahler's Fifth under his direction, this version, taken from its lone broadcast in June 1960, goes some way towards redressing that injustice.

Misha Horenstein

HORENSTEIN conducts Mahler: Symphony No. 5

Previously unissued recording

1. BBC RADIO Introduction (1:34)

MAHLER Symphony No. 5

PART I

2. 1st mvt. - Trauermarsch (12:41)

3. 2nd mvt. - Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz (16:06)

PART II

4. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo (19:49)

5. 4th mvt. - Adagietto (9:54)

PART III

6. 5th mvt. - Rondo-Finale (16:51)

London Symphony Orchestra

Solo Horn: Barry Tuckwell

conducted by Jascha Horenstein

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

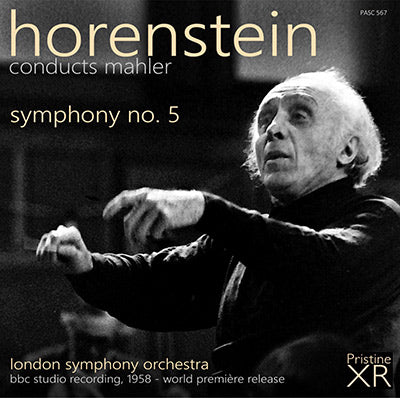

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Jascha Horenstein

Recording from the archive of Misha Horenstein

Recorded 30 October, 1958

BBC Maida Vale Studio 1, London

Total duration: 76:55

NB.The present studio recording of 30 October 1958 preceded an unrecorded concert performance with the LSO two days later, on 1 November. This is a review of that performance:

A GREAT MAHLERIAN: Excellent performance of 5th Symphony

ERNEST BRADBURY, Yorkshire Post, Nov 3 1958

DR. JASCHA HORENSTEIN, who opened the Leeds Festival three weeks ago returned to the Town Hall on Saturday night to conduct the London Symphony Orchestra in Mahler's 5th Symphony. This time there was no suggestion of diffidence, no thought of his filling the breach in the absence of another conductor. Horenstein is a great Mahlerian: the symphony had been exhaustively rehearsed in London for another purpose beside the performance in Leeds, and the large audience (the " House Full " notices were up long before the concert began) was thus authoritatively initiated into a new musical experience.

When the Hallé Orchestra bring Mahler's vast 2nd symphony to Leeds next March we shall have enjoyed a notable Mahler season in this city: but since the 2nd symphony has an unmistakable programme, and a choral section, listeners may not experience the bewilderment that settled on some of them when hearing the 5th. At the first pause, which divides the separate parts of the 5th Symphony's opening section, many programme pages were turned on Saturday by people who thought the first movement must have ended: the idea of an opening funeral march extended over 15 minutes had plainly not occurred to them; they were clearly not accustomed to Mahler's huge architectural opus, nor at all adjusted to his enormous time scale.

Disruptive elements

Another source of puzzlement seemed to be Mahler's actual thematic material—or lack of it, as somebody said. Lengthy themes entail lengthy developments: so much we know from Elgar. But what when, apparently. there are no themes, or rather a multitude of fragmentary ideas that stop and start, break off and renew themselves, or suddenly change places with each other in arbitrary fashion? These seemingly disruptive elements in Mahler's style do indeed show a layout of exposition, development, recapitulation, but it is not that of Beethoven or Schubert, and the listener not prepared to enter into the style and spirit of Mahler, to see this revealed heart of the composer, in the wider sense as related to nerve, muscle, body, head and mind of Mahler, is never likely to understand him.

On the surface of the text of course appreciation was keen enough; there is enough of melody, of orchestral excitement, of deliberate polyphony, to keep listeners attentive at almost any level, and the great ovation given both to conductor and orchestra at the end of the 80-minute work itself proclaimed the effectiveness of the Mahlerian magic.

Absolute fidelity

Horenstein's understanding of the music was certainly excellent. He did not, in fact, break up the work into meaningless fragments, but joined each to each in a continuing flow of musical interest, imparting life and breath to the score in its many transitions of mood and temper, ministering to Mahler's fussy requirements with absolute fidelity (even to the "long pause" between the movements) and drawing from the LSO playing of the utmost clarity and distinction, lovely in phrase and gorgeous in gesture, or snarlingly abrupt in the more stinging sections.

The fragile Adagietto was played with infinite tenderness and Mr. Barry Tuckwell's horn solos in the trio fell on the ear with a golden splendour. Without haste, without any kind of pose or self-conscious emphasis, Horenstein built up the symphony as the intensely spiritual thing it is, from its Faustian opening to the last brassy glories of its finale, and by so doing impressed us by his own art as well as by Mahler's. We hope he will come to Leeds again, with one of the other less-known Mahler symphonies.