This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

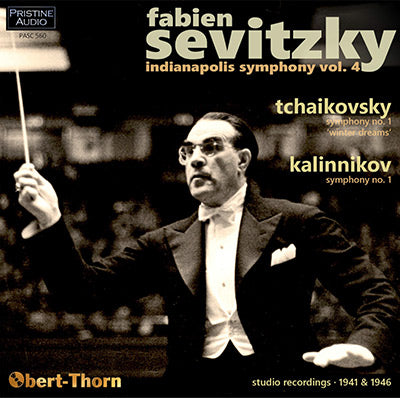

With this fourth volume in our series of the complete recordings of Fabien Sevitzky and the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, we return to the Romantic Russian repertoire for which he was particularly esteemed. Our focus here is on two First Symphonies, both in G minor, separated in composition by nearly three decades. For one composer, it was the start of a brilliant career as a symphonist; while for the other, it was a success not to be duplicated during the remainder of his short life.

Tchaikovsky began work on his first symphony in March of 1866, shortly before his twenty-sixth birthday. It quickly became a trial for him due to his desire to earn the approval of two of his teachers, Anton Rubinstein and Nikolai Zaremba, musical conservatives whose ideals were centered on Classical and early Romantic-era German models. They insisted on changes before they would agree to a performance. The composer obliged, and the two middle movements were presented in St. Petersburg in February of the following year to little acclaim.

Tchaikovsky then went back, for the most part, to his original version, which his friend Nikolai Rubinstein (Anton’s brother) was eager to perform. The Scherzo alone was played at a Moscow concert in December of 1867, again without much success. It was not until a complete performance the following February that audiences finally warmed to the work. Tchaikovsky would go on to revise the score in 1874, and would ultimately look back on this early composition with great pride. (In this recording, Sevitzky performs the last two movements without a pause.)

Vasily Kalinnikov was born in 1866, the same year that Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony was written. He had worked as a choral conductor and an instrumentalist in theater orchestras when Tchaikovsky himself recommended him for two opera house conducting posts in 1892. Kalinnikov’s worsening tuberculosis caused him to resign after a short while in order to move to the more hospitable climate of Yalta on the Baltic Sea. He spent the rest of his life there composing before his death in 1901, shortly before his thirty-fifth birthday. His First Symphony, which dates from this period, was premièred in Kiev in 1897 and quickly traveled to the musical capitals of the world. It remains the work by which he is best known.

Like his recording of Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony (reissued on Volume 1 of this series, Pristine PASC 479), the present works were phonographic premières, and Sevitzky presents both colorful scores with great enthusiasm and obvious affection. The sources for the transfers were first edition American Victor pressings – postwar discs for the Tchaikovsky, and wartime “silver” label copies for the Kalinnikov.

Mark Obert-Thorn

FABIEN SEVITZKY and the INDIANAPOLIS SYMPHONY, Volume 4

Victor Studio Recordings ∙ 1941 & 1946

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13 “Winter Dreams” (1866)

1. 1st Mvt.: Allegro tranquillo (“Dreams of a Winter Journey”) (11:13)

2. 2nd Mvt.: Adagio cantabile ma non tanto (“Land of Desolation, Land of

Mists”) (10:29)

3. 3rd Mvt.: Scherzo: Allegro scherzando giocoso (6:13)

4. 4th Mvt.: Finale: Andante lugubre – Allegro maestoso (11:54)

Recorded 19 March 1946

Matrix nos.: D6-RC-5250-2A, 5251-2, 5252-1C, 5253-1, 5254-2, 5255-1C,

5256-2A, 5257-2C & 5258-2

First issued on RCA Victor 12-0040/4 in album M-1189

KALINNIKOV: Symphony No. 1 in G minor (1894-95)

5. 1st Mvt.: Allegro moderato (9:40)

6. 2nd Mvt.: Andante commodamente (8:52)

7. 3rd Mvt.: Scherzo: Allegro non troppo – Moderato assai (7:32)

8. 4th Mvt.: Finale: Allegro moderato (9:28)

Recorded 7 & 8 January 1941

Matrix nos.: CS 057576-1, 057577-1A, 057578-1, 057579-2, 057580-1,

057581-2, 057582-1 & 057583-1

First issued on Victor 18187/90 in album M-827

Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra ∙ Fabien Sevitzky

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Special thanks to Nathan Brown and Charles Niss for providing source

material

All works recorded in the Murat Theatre, Indianapolis, Indiana

Total Timing: 75:20

Fanfare magazine review

Sevitzky is a brilliant success, completely capturing the music’s soaring grandeur. Enthusiastically recommended!

With this release (Volume 4), Pristine Audio and Mark Obert-Thorn continue their series of reissues of recordings by Fabian Sevitzky (1891–1967), the nephew of Serge Koussevitzky. (At Serge’s insistence, Fabian abridged his surname to avoid confusion and competition between the two.) Originally a double bassist in the Philadelphia Orchestra, in 1925 he founded the Philadelphia Chamber String Simfonietta, a 17-member ensemble drawn from the orchestra’s ranks that made several recordings for Victor (also reviewed in these pages). Sevitzky then led the Indianapolis Symphony from 1937 to 1955, where he continued his recording career with Victor from 1941 to 1946, plus two sessions with Capitol in 1953. As with Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony that Dan Morrison applauded in Volume 1, both of these recordings were world premieres of these works on disc. All three of these works have prior CD releases on the Historic Recordings label, which I have not heard.

This disc presents an especially felicitous coupling, with two early symphonies by their respective composers, and both cast in G Minor. The recording of the Tchaikovsky First Symphony dates from March 19, 1946. Tchaikovsky later said of this symphony that he retained a soft spot for it in his heart as “a sweet sin of my youth,” and I heartily concur; this has long been a special favorite of mine, and I prefer it even above the far more famous Fifth Symphony. Sevitzky’s conducting in the first three movements is quite brisk throughout, with a firm command of the score’s architecture and a fine ability to bring out subsidiary lines. More than in any other rendition I’ve heard, the essentially balletic feel of the music is brought out. The finale in Sevitzky’s hands, while well proportioned, is a bit of a let-down after the previous exhilaration; here Sevitzky adopts a tempo slightly slower than the norm and emphasizes the quasi-fugal part entrances in a manner that seems a bit four-square, missing the roaring excitement and passion that Evgeny Svetlanov elicits in his nonpareil first studio recording. Also, most curiously, Sevitzky substitutes a military drum for the timpani in the final percussion roll before the concluding orchestral chord, and downplays it to boot, ending not with a bang but a whimper. Despite this, the recording makes a strong case for this work, and must have done so in introducing it on records to the public 73 years ago.

The Kalinnikov First holds an extraordinary place in my musical affections. I first encountered it in high school, when playing the finale in an arrangement for concert band. I immediately fell hopelessly in love with it, ran out, and bought a recording (Kirill Kondrashin with the Moscow State Philharmonic, more on which in a moment). It still remains among my absolute favorite works in any genre—stunningly beautiful melodies, especially the drop-dead gorgeous first theme of the Andante commodamente second movement that is brought back at the end of the Allegro moderato finale in a glorious peroration of boundless optimism and joyful exultation in all that is truly good and beautiful. (I’ve listened to this work literally hundreds of times in my life, and each time the last section of the finale arrives I have to stop whatever I’m doing and “air conduct” along with it—and then I have to replay it and do the same thing.)

The Kalinnikov is from Sevitzky’s very first set of recording sessions in Indianapolis, on January 7–8, 1941. As in the Tchaikovsky First, Sevitzky here takes the opening movement at a fleet, though never rushed, clip. Unfortunately, no doubt due to restrictions of the 78-rpm format to keep the set at an even number of sides, the exposition repeat is not taken, cutting the movement’s length from its usual 13–14 minutes to only 9:40. (This may also have been a common performing practice of that time, as Toscanini makes the same major cut in his 1943 broadcast of the work.) In contrast to the Tchaikovsky First, however, the second movement is given the slowest rendition on any recording, coming in a very broad 8:52 (the more typical Kondrashin by contrast comes in at 6:06). But it works superbly, being beautifully expansive and not at all dragging. While the outer sections of the scherzo once again move along smartly, Sevitzky slows down significantly for the trio section, creating a most effective atmosphere of languorous, dreamy Asiatic Orientalism.

This brings us to the finale, which requires separate discussion, as this is the point where almost all recordings come a cropper after being more or less competitive in the first three movements. At the aforementioned reprise of the theme from the second movement, about 2/3 of the way into the finale, where the meter changes from 2/2 to 3/2, Kalinnikov indicates L’istesso tempo; then, after a brief return to the finale’s main meter, tempo, and thematic material, the broad melody from the slow movement returns for a second time to close the work in 3/2, this time with a tempo marking of Maestoso. The directive L’istesso tempo (the same tempo) can be understood in two different ways: either to keep the beat (pulse) constant, or to keep the total time for a single measure constant, resulting in either an acceleration or deceleration of the beat, depending on the direction of the shift. Here, four older recorded performances—Sevitzky, Golovanov (live 1945, unfortunately in poor sound with bad pitch fluctuations), Rakhlin (studio 1949), and Kondrashin (studio 1961)—follow this second alternative by effectively equating one measure of 3/2 with two measures of 2/2, thereby in effect decreasing the tempo by one-third. I am convinced this is what Kalinnikov intended. All other recordings, mostly more recent ones—Toscanini, Scherchen (live 1951, also in poor sound), Svetlanov (2 versions), Dudarova, Järvi, Kuchar, Friedmann, Ashkenazy, Bakels—take the first alternative to various degrees, which completely negates the effect of majestic breadth achieved by the second alternative and spoils the movement (though Svetlanov’s first recording from 1968 almost makes it work). Here Sevitzky is a brilliant success, completely capturing the music’s soaring grandeur. If due to the older sonics and the cut in the first movement this version does not quite equal the versions by Kondrashin (a recording I must enter into the Classical Hall of Fame some day) or Rakhlin (almost competitive with Kondrashin except for the bizarre intrusion of a badly over-miked triangle beating incessantly throughout the close of the finale, apparently attempting to imitate the tolling of church bells), it is still a very fine achievement.

Mark Obert-Thorn has done his usual stellar remastering work here. In closing, I will unashamedly filch some lines from Dan Morrison’s review of Volume 1: “Fabien Sevitzky appears to have been an excellent conductor, eminently deserving of renewed attention. In these performances he imposes tight orchestral discipline and firm tempos, but he also generates rhythmic vitality, urgent momentum, and dramatic excitement. The Indianapolis Symphony, too, long ensconced as a respected but not renowned member of the second tier of American orchestras, shows itself to have been a very fine ensemble in this era. The sound quality of Obert-Thorn’s restorations is good enough that listeners could contemplate purchasing this release simply for enjoyment of the works included, and not just for its historical value.” Enthusiastically recommended!

James A. Altena