This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

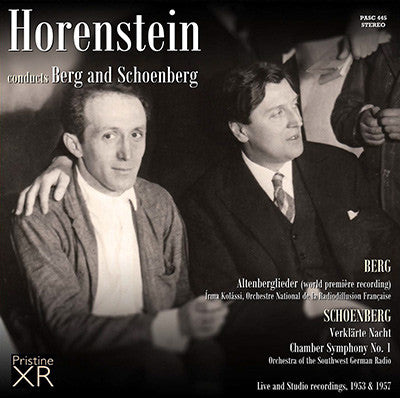

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

Jascha Horenstein's Berg and Schoenberg: straight from the heart of the Second Viennese School

"This is a magnificent disc ... we should all welcome an alternate viewpoint" - Fanfare

Once again I'm grateful to Misha Horenstein for his assistance in preparing this release and offering access to his incredible archive of recordings conducted by his cousin, Jascha Horenstein. Each of the three recordings here presented its own unique remastering challenge. The Berg was perhaps the most straightforward - effective microphone placement for this clean, clear broadcast recording allowed me to bring out the warmth of the lower orchestral timbres as well as the clarity in the upper registers of the voice.

The two Schoenberg recordings were made by Vox in stereo in 1957, and suggest their sound engineers were struggling with the concept of the stereo soundstage somewhat. Indeed, the Chamber Symphony was recorded in such a way as to suggest it might never have been intended as a proper stereo recording at all, but rather a mono recording on two tracks for mixing to mono at a later date, such was the bizarre stereo separation. Neither sounded too great either, and I've had to wrestle both with stereo imagery and with orchestral tone to get the best out of them.

Both have been significantly improved with XR remastering assisting in the orchestral timbre (the Verklärte Nacht employs Schoenberg's orchestration for string orchestra), and whilst the extremes of bizarre stereo separation heard in the original Chamber Symphony recording have been tempered, it has to be admitted that neither presents ideal stereo imagery to the modern listener. Nevertheless, the latter in particular has been rendered far easier on the ear now its tendency to pull the listener from one speaker extreme to the other has been reduced!

Andrew Rose

2. Sahst du nach dem Gewitterregen den Wald?

3. Über die Grenzen des Alls

4. Nichts ist gekommen

5. Hier ist Friede

Írma Kolássi, mezzo-soprano

Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Française

Live broadcast, 4 May 1953

French première

SCHOENBERG Chamber Symphony No. 1 (Kammersymphonie) Op. 9b

Orchestra of the Southwest German Radio (SWDR)

Stereo studio recordings, October 1957

Jascha Horenstein, conductor

HORENSTEIN AND THE SECOND VIENNESE SCHOOL

by Misha Horenstein

Horenstein's allegiance and devotion to Schoenberg and his school developed at a very early age. Following the First World War he became closely acquainted with several of Schoenberg's pupils and it was probably through one of them that, in May 1918, he attended ten public rehearsals of the Chamber Symphony no. 1 given by the composer in Vienna. He recalled the occasion in a BBC interview many years later:

A circle of young musicians had asked Schoenberg’s permission to organize ten public rehearsals of the Kammersymphonie. Attendance was only by invitation and there was no public concert afterward, only the ten rehearsals. You must realize that today we do Schoenberg as simply as we do Beethoven but in 1918 it was an enormous problem. The piece was too difficult and musicians didn’t want to play it, so those ten rehearsals were organized which Schoenberg conducted himself, and at the ninth or tenth rehearsal he played the whole piece, even twice, to the great pleasure of all concerned. I was present at all ten rehearsals and made extensive notes in my score. I still remember Schoenberg’s remarks, so much so that even if today I would do certain pages in the piece differently, for example beating some passages in two instead of in four, I feel compelled to beat in four because that was the way Schoenberg did them.

By his own admission, we know that Horenstein also attended a number of Schoenberg’s public lectures and that in 1918 registered as a member of his Society for Private Musical Performances, which was established following the ten rehearsals of the Kammersymphonie. It was probably at one of these occasions that he also met Berg and Webern for the first time and in later years it amused him to recall how these two key figures of twentieth century music then functioned as ushers in charge of controlling membership tickets at the entrance to those events. That period was surely an age of greater humility than ours.

The Kammersymphonie and Verklärte Nacht, two of the works Horenstein encountered at a young age, remained permanently in his repertoire. His first known performance of the latter took place in 1927 at one of his early concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic. The event attracted a large crowd that “flocked to receive the musical gospel,”[1] including Schoenberg, whose work was the main focus of the following day’s reviews. "A real delight and a feast for the ears”, wrote one critic, “in the conductor’s highly expressive and disciplined hands the melody seems improvised,” an observation confirmed and often repeated by other reviewers in different contexts throughout Horenstein's career. Schoenberg himself, according to the same critic, was delighted by the performance and “had to shout bravo” before joining Horenstein on stage for the applause.[2]

Such were Horenstein's successes with Verklärte Nacht that as early as 1929 the work began to replace Mahler's First Symphony as his musical calling card. Reviews of that period mention “the stunning clarity and almost frenzied expressiveness”[3] he found in Schoenberg's youthful opus, still an unknown quantity to most people, while after a performance of the work in Paris another critic was relieved that “for once Herr Schoenberg did not devour anyone”.[4] For the reviewer from Le Figaro the most important point was that Horenstein “makes the music comprehensible”[5], which is arguably the highest form of compliment for anyone performing modern music.

Horenstein’s thoughts on Verklärte Nacht were published in a music journal shortly after his 1927 Berlin performance. The article formed part of a tribute to the composer published after his appointment to Busoni's old position in the German capital as director of the master class in composition at the Prussian Academy of the Arts. Horenstein's informative and scholarly thoughts eloquently identify and put into context some aspects of Schoenberg's style that would appeal to the educated listener, and could be viewed as a model to emulate for writing of this kind. Schoenberg himself was very pleased by the tribute and wrote to Erwin Stein that Horenstein's analysis of his early style was “very nice and, I think, correct.”[6]

VERKLÄRTE NACHT, by Jascha Horenstein

The detachment of tonality in Arnold Schoenberg's creative work has reached its first stage in the string sextet Transfigured Night. The decomposition of the diatonic scale, the use of harmonic combinations of the twelve-tone chromatic system in this work already indicate a clear direction, which then led to Pierrot and to the Five Orchestral Pieces.

Everything in this string sextet was "new" at the time of its composition, a time when Richard Wagner's musical dramas and Liszt's tone poems stimulated all young composers to follow suit. Schoenberg, however, turned to chamber-music and, by prefixing the score with Richard Dehmel's poem, approaches the problem of applying a program within a chamber music setting for the first time.

Already in this piece, symmetric-periodic construction is temporarily replaced by free architecture, without loss of clarity in its formal organization. This leads to an expanded Lied form, in which we can clearly recognize five parts in analogy to the poetic model.

Today many people say - the same, who twenty-eight years ago, when the work was composed, did not know what to do with this stroke of a genius, so new and completely incomprehensible to them was every bar - today they say this music derives from Wagner. This is not the case.

Schoenberg doesn't set out from the elements of Wagner's musical language; organic sound phenomena, which dominate in the music of Tristan, stimulate him to a consequent abstraction: chromaticism and enharmonics, the crossing of parts, the unresolved suspensions, the conscious emergence of surprising harmonic turns, the avoidance of diatonic cadence resolution. Through his intensification and further development of the "Tristan harmonies" Schoenberg attains a compactness of expression and, intensifying the tension, the most consistent chromatic concentration. In its energetic lines this impressionist piece is utterly expressionistic.

The tremendous intensity, which here reaches the materialization of a sensual event and thus also leads the "program" to its only solution, brings harmonic and tonal combinations which - deviating from everything conventional - carry the characteristic traits of Schoenberg's later works.

The inner dynamics of Transfigured Night are dominated by an incessant change of propulsive and retreating groups of motives; they constitute the rubato-melos, which is so characteristic in Schoenberg's early works. In addition to this Schoenberg also exhausts the ultimate melodic and tonal possibilities of the stringed instruments. The sonorous magic of this work, written in 1899 by a twenty-five year old, is without equal.[7]

Verklärte Nacht was a piece Horenstein performed several times over in every country he visited, with almost every orchestra he conducted and in every period of his career to great public acclaim. He conducted the Kammersymphonie less often, probably because of its greater difficulty and more astringent musical language. The two Schoenberg items presented here, originally published on the Vox label, are his first recordings of these works but there are several others of both, taken from live concerts in different places.

A WORLD PREMIERE

Horenstein's relations with Webern were, in his own words, “very superficial”, but with Alban Berg, whom he whimsically described as “a renaissance type with a touch of Oscar Wilde in him, tall, languid and very sophisticated”,[8] he developed a long and close friendship that only ended with the Austrian composer’s premature death in 1935. During the Weimar era Horenstein attended the world premiere of Wozzeck in December 1925 and conducted several works by Berg in different places, including the world premiere in Berlin of the orchestral version of the Lyric Suite.

In the early 1930s, as music director of the Düsseldorf Opera, Horenstein directed eleven fully-staged performances of Wozzeck, the opera's eighth presentation overall, which brought him and the Düsseldorf Opera nationwide celebrity, recognition and prestige. Berg attended the presentation of Wozzeck, including some of the rehearsals, and was also present at each of Horenstein's other performances of his music during that period.

After the Nazi takeover, Horenstein conducted the first performance in Belgium of Berg's Violin Concerto in 1938 with its dedicatee, Louis Krasner, as soloist. He did not perform his music again until November 1950 when he directed the French premiere of Wozzeck (attended by a very young Pierre Boulez, hearing the opera for the first time, "which left an immense impression"), and then on 24th January 1953 the world premiere of the Altenberglieder in Rome with soloist Elsa Cavelti (see programme, right). At the time there were doubts about whether the Rome performance was in fact a world premiere and the program booklet does not even mention it.

Two of the five songs had had their first performances in Vienna in 1913 at a concert conducted by Schoenberg, but following hissing and interruptions by outraged members of the audience incensed by the music's uncompromising, abstract modernity as well as by Altenberg's aphoristic texts, fist fights broke out, a pistol was drawn, the police had to be called in and the concert was abandoned. Known subsequently as the Skandalkonzert, this event, like the riots that attended the premiere in Paris of the Rite of Spring a few months later, caused one of the greatest tumults in musical history.

Berg himself was devastated by the scandal and more or less abandoned the work, his first orchestral composition, which was not published until half a century later, long after the Rome premiere. Horenstein himself was unsure whether his performance, the score and parts of which were still in manuscript form at the concert, was indeed the world premiere:

I did not and still do not claim that it was a world premiere of the 'complete' cycle! In 1953 I asked my friends at Universal Edition about any previous performance of this piece ... and they could not find anything on record. Though I still do not claim it, it is quite possible that it was the first 'complete' performance![9]

Further research has confirmed that the performance in Rome was in fact the complete work's world premiere, but although the concert was promoted by the Italian state broadcaster RAI, and performed by its orchestra, no copy of the broadcast recording has been found. Horenstein conducted the work again in Florence (soloist Eugenia Zareska) and in London (with Írma Kolássi) but the performance presented here, documenting the French premiere given in Paris on 4th May 1953 just four months after its world premiere in Rome, is the only one of these to have been preserved on record.

[1] Adolf Weissman: B.Z. am Mittag, (No. 72), Berlin, March 15, 1927

[2] Franz Wallner, Berliner Morgenpost, 16 March 1927

[3] Robert Oboussier, Le Menestrel, 12 April 1929, p.169

[4] Jacques Yanin, L'Ami du Peuple, 24 March 1929

[5] Stan Golestan, Le Figaro, 27 March 1929

[6] Letter to Erwin Stein, 13 May 1927 (Schoenberg Archive)

[7] Pult und Tackstock 4, (No. 2, pp.24-25), March/April 1927

[8] Quoted in The Posthorn, Journal of the Jascha Horenstein Society, Fall 1973

[9] Letter to Donald Harris, 17 December 1972 (Ohio State University)

Fanfare Review

The orchestra captures that atmosphere better than any performance I know...

This was the French premiere of Berg’s op. 4, Five Songs on Picture Postcards by Peter Altenberg. They were to be sung in Vienna in 1913, but the first two songs caused a riot comparable to that of Le sacre in Paris, and the performance had to be abandoned. The complete set was not performed until 1953, a few months before this broadcast. This performance is as atmospheric, in its hot-house eroticism, as any you will hear. Irma Kolássi is in gorgeous voice and sings with smoldering warmth, although she does not attempt the octave leap to a high C that closes the third song, “Über die Grenzen des Alls.” The orchestra captures that atmosphere better than any performance I know. The warmth and fullness of this monaural radio recording are remarkable, but even the geniuses at Pristine cannot restore high frequencies that are not in the original, so the percussion are slighted, and some noticeable noise and distortion remain. Nevertheless, this disc provides a winning experience. The unique timbre of Jessye Norman’s soprano is ideal for this music (and she hits that ppp high C perfectly, at perhaps p—most singers have to produce it at least f). Her Sony recording is recommended despite Pierre Boulez’s rather cool accompaniment and the so-so recorded sound. In Fanfare 33:5, Steven E. Ritter concurred but also recommended Christiane Iven’s performance on a superb-sounding Pentatone SACD.

The First Chamber Symphony was one of the major turning points in music; it is a masterpiece of concision despite its prolixity of ideas, an exuberant outpouring despite its chamber-music origins. Its 15 instruments defined a new orchestra for the 20th century, one that had been absent for 150 years: one instrument to a part. Why Schoenberg expanded it for full symphony orchestra (in 1922 and again in 1935) remains a mystery, at least to me, for it totally alters the work’s character. Jascha Hornestein makes the most of the arrangement’s gushing Romanticism yet maintains as much of the original’s outgoing spirit as is humanly possible, but I would still prefer a merely decent performance of the original.

I am more comfortable with the 1917 and 1943 expansions of Verklärte Nacht: Because instrumental balances have not been upset, the orchestral version remains the same Romantic tone poem as its string-sextet original. But Horenstein does make it a different piece, going all out with Romantic fervor. It’s overwhelmingly beautiful, but (and challenging Horenstein’s Schoenberg is like challenging Furtwängler’s Bruckner!) something is lost along the way. The couple walking beside a river on a dark, cold night are now soaring through space; the tension and uncertainty of their relationship are absent, so that his loving acceptance of her condition is no longer felt. In essence, the story has been turned on its head: The first part is now all glory, the more easy-going second part now something of a comedown.

The 1953 radio recording is monaural. Although the two studio recordings were both made for the Vox label in 1957, Verklärte Nacht appears to be in stereo, the Chamber Symphony in mono; a 1961 Schwann catalogue confirms this. As I remember, the original LP sounded quite harsh; Pristine’s transfers have smoothed both recordings out nicely. The stereo violins shine, but the low end remains muddy in Verklärte Nacht. As usual with Pristine, there are no song texts; they can be found on the Net, and a YouTube performance allows you to follow a reduced score (with German text) page by page as the performance proceeds.

I do realize that my views of Schoenberg’s revisions and of Horenstein’s way with them will be shared by only a minority of listeners. My job is to tell you what I think and feel. This is a magnificent disc despite my carping; there are plenty of recordings that play it my way, and we should all welcome an alternate viewpoint.

James H. North

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:3 (Jan/Feb 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.