This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

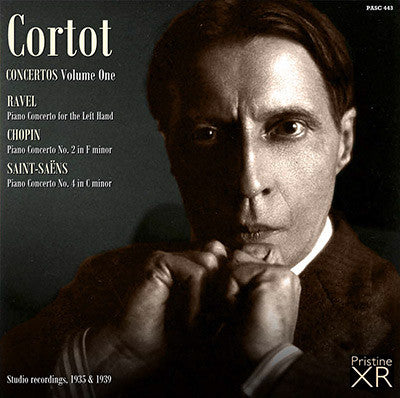

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

Cortot's Concerto Recordings, Volume One - Piano Concertos by Ravel, Chopin and Saint-Saëns

"The piano sound on Pristine’s remastering is remarkably full and rich. This is an essential disc for pianophiles" - Fanfare

Alfred Cortot's extensive studio recordings for EMI included very few with full orchestra. He seemed more at home in a solo or chamber music environment when in the recording studio, and yet these recordings demonstrate amply just what a fabulous concerto player he also could be.

Andrew Rose

RAVEL Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

conductor: Charles Munch

Recorded Salle Chopin, Paris, 12 May 1939

Matrix Numbers 2LA.3059-62

Issued as HMV DB.3885-86

CHOPIN Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21

Orchestra, conductor: John Barbirolli

Recorded Abbey Road Studio 1, 8 July 1935

Matrix Numbers 2EA.1506-13

Issued as HMV DB.2612-15

SAINT-SAËNS Piano Concerto No. 4 in C minor, Op. 44

Orchestra, conductor: Charles Munch

Recorded Abbey Road Studio 1, 9 July 1935

Matrix Numbers 2EA.1514-19

Issued as HMV DB.2577-79

Chopin, Piano Concerto No. 2 - Historic Review

I have been

able to get down from the office two other recordings of this—the

Columbia (Marguerite Long and the Paris Conservatoire Concerts

Orchestra: Gaubert. LX4-7}, and the Rubinstein-L.S.O. (Barbirolli). This

is H.M.V. DB1494-7. Each {cutting slightly the first movement) takes

seven sides, and has a fill-up: Mile. Long playing the Mazurka, Op. 59,

No. 3, and Rubinstein the C sharp minor Waltz, Op. 64, No. 2. I have no

strong preference among the three. The Col. tone is distinctly slighter.

On the whole Rubinstein’s is the biggest and most even, but I find

Cortot’s the most interesting interpretation. There are few pianists

whose poetry I find more congenial, though he does not record as well as

some others. The balance and shaping of a few of those slow movement

phrases are worth analysis. But Rubinstein produces a more impressive

flow of tone, where that is wanted. Neither H.M.V, set, in the recorded

orchestral tone, comes to my ideal. Cortot’s last side but one seems to

me, again, the more pure Chopin in impulse. These things are hard to

analyse (though I am sure they can be divided down to minute

particulars), and quite mad to argue about. One just enters some

particular interpretative artist’s heaven and is thankful to let

everybody else do likewise with his or her blissful abode.

Saint-Saëns, Piano Concerto No. 4 - Historic Review

At

side 2, 33, a second melody follows the chorale, and there is some good

Schumannesque matter for a minute or two. The air darkens, and the

pianist wreaks mightily upon the chorale, towards the end of the side.

Side 3 begins with the secondary melody, which is now pondered upon very

prettily. All the way, Cortot's feeling for the graces and simple

depths of the music is entirely enjoyable. His quality does not record

sensationally, as we know, but he is always, for me, one of the most

satisfying of pianists, because of his fine feeling, his beautiful

timing and phrasing, and his blend of firmness and suavity.

WRA, The Gramophone, May 1939, May 1938 (Exerpts)

Fanfare Review

All three concertos are given splendid performances here - essential

The French-Swiss pianist Alfred Cortot (1877–1962) was never known for spotless technique, and if that is at the top of your list of requirements for listening to keyboard concertos you might want to pass this up. Everyone else, however, should snap it up. All three concertos are given splendid performances here. Although Pristine puts the Ravel first on the disc, I started the headnote with the Chopin because it is to my ears the most special of the three.

Cortot studied with a pupil of Chopin’s, and so this can be said to be music-making fairly close to the source. But our knowledge of that biographical fact should not influence the way we hear this. There were probably many pianists who studied with pupils of Chopin whose work we would have no interest in. What distinguishes this performance is the poetry of the playing, the subtle use of rubato throughout, the way Cortot shapes phrases giving them both firmness and suppleness at the same time. This is playing of great nuance and shading, some of it staying long in the memory after the recording is finished. The Larghetto of this concerto is by itself more than worth the price of the disc. It is an object lesson in Chopin playing. Cortot employs an infinite variety of dynamics. Between forte and piano is a whole wide world, and he carefully gauges his dynamic level so as to create a constant sense of flow and forward motion. I have heard this recording in earlier releases, and Pristine’s Andrew Rose can be said to have opened up a new world with his remastering here. Never has the piano sound been so alive, and never has the degree of colors employed by Cortot been as apparent.

Cortot was a thorough musician—an important conductor as well as pianist—and it is the thoroughness of his musicianship that shines through these performances. What I find particularly interesting is that although there are occasional wrong notes, there are also passages of surprising technical brilliance. The implication of this, at least as I hear it, is not that he couldn’t achieve a high level of technique but rather that it was not of prime importance to him. Eloquence of phrasing, maintaining a sense of freedom throughout a performance, giving the impression of creating the music while performing it, these were his guideposts.

The Ravel and Saint-Saëns performances are on a similarly high level, although I found the very ending of the Ravel surprisingly timid, lacking in the snap that I expect there (and that the performance had led me to expect here). The dark drama of the Ravel, and the glistening sparkle of the Saint-Saëns, all of this and more is conveyed in these spontaneous recordings. The final bars of the Ravel notwithstanding, the accompaniments of Barbirolli in the Chopin and Munch in the other two are as superb as you would expect. The Ravel dates from 1939; the Chopin and Saint-Saëns date from 1935. The piano sound on Pristine’s XR Stereo remastering is remarkably full and rich. This is an essential disc for pianophiles.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:2 (Nov/Dec 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.