This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

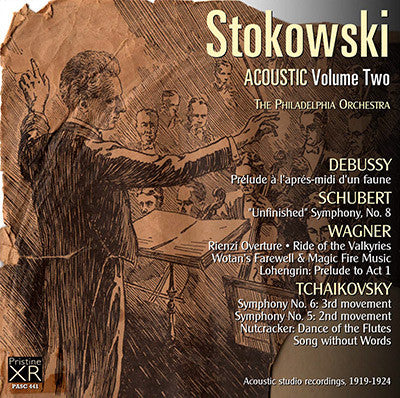

Stokowski's earliest recordings of Debussy, Schubert, Wagner & Tchaikovsky

This is the second of four volumes dedicated to the acoustic recordings Stokowski made with the Philadelphia Orchestra between 1919 and 1924. By acoustic we mean a recording process entirely devoid of electrical equipment: a weight-driven cutting lathe on which master discs were cut, the minute variations in the grooves being driven entirely by the vibrations reaching the cutting head through a large horn, concentrating as much acoustical energy as possible from the orchestra. This frequency- and dynamically-limited process was the only means of recording sound for well over a quarter of a century, during which time the technology progressed from being considered a novelty toy to something which, although recognised as limited, was of serious artistic value. Stokowski was one of very few internationally known musical artists to see the progression right through as a recording performer from the acoustic horn to the multitrack studio. His acoustic beginnings are, like so many, often consigned to ancient history.

This volume uses the latest 21st century technology to clean up, clarify, stabilise and bring you the best possible sound from recordings almost a century old. Volume One (PASC192) was restored 6 years ago - in that short time considerable further strides have been made that have allowed me to find even greater fidelity and clarity from these marvellous relics of an almost lost age of sound recordings.

The transfers were made by Edward Johnson from his collection of (relatively) quiet-surfaced Victor original 78s.

Andrew Rose

-

DEBUSSY Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune

Recorded April 28, 1924.

Disk: Victor 6481, Matrices: C-21057-5, C-21058-5

-

SCHUBERT Symphony No. 8 in B minor, "Unfinished"

Recorded April 18, 1924.

Disks: Victor 6459, 6460, 6461

Matrices: C-29052-5, C-29053-5, C-29054-5, C-29055-4, C-29056-5, C-29057-5

-

WAGNER Rienzi - Overture

Recorded May 8, 1919.

Disks: Victor 74602, 74603 Matrices: Victor C-22815-3, C-22816-3

-

WAGNER Die Walküre: Ride of the Valkyries

Recorded March 25, 1921.

Disk: Victor 74684 or HMV DB 387 Matrix: C-24987-4

-

WAGNER Die Walküre: Wotan's Farewell and Magic Fire Music

Recorded December 5, 1921.

Disk: Victor 74736 Matrix: C-24124-12

-

WAGNER Lohengrin - Prelude to Act 1

Recorded April 28, 1924.

Disk: Victor 6490 or HMV DB 839 Matrices: C 30021-2, C 30022-1

-

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 6 - March (heavily cut 3rd mvt.)

Recorded April 18, 1921.

Disk: Victor 74713 Matrix: C-24628-11

-

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 - 2nd mvt. - Andante cantabile con alcuna licenza

Recorded April 30, 1923.

Disks: Victor 6430, 6431 Matrices: C-27904-2, C-27905-1, C-27906-2

-

TCHAIKOVSKY The Nutcracker - Dance of the Flutes

Recorded February 13, 1922.

Disk: Victor 66128 Matrix: B-24938-6

-

TCHAIKOVSKY (arr. Stokowski) Song Without Words, Op. 40, No. 6

Recorded April 28, 1924.

Disk: Victor 1111 Matrix: B-27065-7

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Leopold Stokowski, conductor

Fanfare Review

They are life-enhancing in a way that so few new recordings ever are

In 1981, I hosted a semester-long weekly series on Harvard Radio devoted to Leopold Stokowski. If you had told me at the time that we one day would have the historic material now available on these two CDs and in such fine sound, I never would have believed you. I think that throughout that whole radio series I had only one LP available to me of monaural content from our station’s library. Fortunately Stokowski’s admirers are a dedicated bunch, and can support Pristine’s enterprise of giving us CDs with small commercial potential. The evening I first played these discs I had a terrible time falling asleep, such is the Stokowski magic they contain. To love recordings enough to write for Fanfare you probably have to be a little bit crazy. I freely admit to suffering from an as yet undefined malady I would call “Stokowski-induced mania.” Of these two CDs, the one featuring the most recent material clearly is aimed at my fellow sufferers. It collects all the post-acoustic era recordings by Stokowski until now unavailable on CD and which are in the public domain in France, where Pristine Audio is based. For instance, there is a previously unissued 1945 session by the New York City Symphony playing the Prelude and Libestod from Tristan, of which only the first and last 78-rpm sides survive. They nevertheless reveal the tremendous sense of style Stokowski had imbued his one-year-old ensemble with. He is alternately vigorous and sensitive in selections from Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, with the NBC Symphony performing with the precision and clarity this Toscanini trained ensemble was known for.

The remaining items on the CD feature “Leopold Stokowski and his Symphony Orchestra.” Perhaps the greatest draw for the non-specialist collector is the music from Tannhäuser. The Overture opens with a blend of reverence and sensuality peculiar to Stokowski. The second statement of the Pilgrim’s Chorus is positively ecstatic. At its peak, the Venusberg Music reaches a pitch of controlled frenzy only Stokowski could achieve. Although he was a noted lady killer, there also was a feminine side to Stokowski, expressed in his face’s sensitivity and the delicacy of his hands. The overall effect was an apparent androgyny that held a mysterious sway over orchestral players, helping to produce the remarkable Stokowski sound we hear here. As Wagner’s orgiastic music subsides, it is replaced by something like post-coital tristesse. In act III’s Prelude, Stokowski portrays the fever in Tannhäuser’s mind and his need for redemption. The brass players, drawn from the New York Philharmonic, cover themselves with glory in their chorales. While Solti and Doráti have given us memorable, stand-alone accounts of the Overture and Venusberg Music in stereo (Solti has the Dresden Overture and the Venusberg Music as separate tracks), nothing in my experience matches Stokowski in these highlights.

Another great reason to own this disc is Stokowski’s arrangement of Dido’s Lament from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. It is filled with the archaic-sounding string sonorities Stokowski loved to exploit in his orchestrations of Baroque music. There’s a wondrous feeling of sorrow in the repetitions of Dido’s “Remember me” in the violins. Stokowski conducted music from Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony in the 1947 movie “Carnegie Hall,” so RCA at the time apparently saw the commercial value of his leading an abridged version of the slow movement that would fit on one 78. Judging by the performance’s passion, Stokowski must have been happy to oblige. Two years later, he conducted the “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker for a children’s disc, with Mozart’s “Sleigh Ride” on the flip side. New York Philharmonic pianist (and future conductor) Walter Hendl plays the celesta unusually expressively, as Stokowski brings out the menace underlying Tchaikovsky’s fantasy. Restoration engineer Mark Obert-Thorn has contrived highly listenable sonics throughout this CD, although the Tannhäuser excerpts sound rather cramped for their 1950 recording date. Even if you’re not collecting everything Stokowski ever did, this disc is a blast.

In 1977, a then elderly friend loaned me Stokowski’s 1923 acoustic 78s of the slow movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Even played on my inexpensive equipment, I was amazed at the sound quality. Now we have this and other acoustic recordings by Stokowski, made between 1919 and 1924, in new remasterings by Andrew Rose. The results are highly illuminating. Rose has achieved a generally listenable sound from all this material, and their musical content for the most part is first-rate. The main drawback for the acoustic technique in recording an orchestra is the absence of hall atmosphere, with very little air around the instruments. The balance on these recordings, though, in the main is very good. They document a period in Stokowski’s career when, at about age 40, his interpretations tended to be less idiosyncratic than they later became. A Metropolitan Opera bassist who played under Stokowski in the early 1960s told me that the conductor “did things just to be different.” There really is very little about these early recordings that the most Toscanini-minded purist could find objectionable. The one recording where the music overtaxes the engineering technique is that of the Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. Stokowski had tried twice previously to make a recording of the work, before finally releasing this 1924 effort. The evanescence of the string writing really is beyond the capacity of the acoustic equipment to capture. Still, there is much to enjoy in the eloquent playing of flutist William Kincaid, oboist Marcel Tabuteau, and a marvelous first horn. They respond to the flexibility of Stokowski’s interpretation with great tenderness. Perhaps the conductor had reservations about this recording as well, for he rerecorded the piece electrically only three years later.

Stokowski’s Schubert “Unfinished” is a great performance, from a time when complete symphonies were still rare on records. As one can hear on his London Philharmonic recording from the 1960s, Stokowski was fascinated by the sound of this work. For an early 1950s performance in San Francisco, he retouched the orchestration and also added an extra wind instrument. Even this 1924 recording suggests the vivid, haunting colors Stokowski found in the piece. The ensemble is vigorous and highly disciplined, quite different from, say, Bruno Walter’s approach. There is no exposition repeat in the first movement, repeats being sparing on 78s.

The Wagner recordings here are pretty sensational. Stokowski’s Rienzi Overture really swings, even though it is cut to fit onto two 78 sides. The orchestral sound possesses a suavity I’ve rarely encountered elsewhere. The Ride of the Valkyries has a dramatic tension that would have pleased Toscanini, while the tone of the performance is something the Italian maestro never achieved. The brief excerpt from Wotan’s Farewell and Magic Fire Music has all the magic of Stokowski’s classic Houston version for Everest, but with a better orchestra. If any recording on this CD stands out as an engineering triumph, it’s the Prelude to Act One of Lohengrin. Somehow the acoustic horn managed to capture the rapt beauty of Stokowski’s beautifully proportioned reading.

The third movement of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony is a bit of a throw-away. It is cut to shreds to fit onto one 78 side, and the orchestra’s response is somewhat perfunctory. As I mentioned earlier, we do get a complete account of the slow movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth—beautifully molded in its playing and paced with great sensitivity. It is not as individual as the abridged version on the previous CD in this review, but it is accomplished in a way very few conductors could achieve. The Nutcracker dance has great charm, while Tchaikovsky’s Song Without Words is one of those romantic Stokowski orchestrations that seems to linger in the atmosphere after it ends. Pristine also gives us a cover with a wonderful drawing of the young Stokowski, from the record sleeve of one of his acoustic 78s.

If this exploration of the world of acoustic recordings of orchestras whets your whistle, I would also recommend Biddulph’s set devoted to the discs of Willem Mengelberg and the New York Philharmonic. These two new releases from Pristine fill out our view of one of the greatest conductors of all time. I’m aware that they are likely to appeal to a specialized audience, but they are life-enhancing in a way that so few new recordings ever are. There’s one more volume of acoustic Stokowski on the way from Pristine, and I can’t wait.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:2 (Nov/Dec 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.