This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

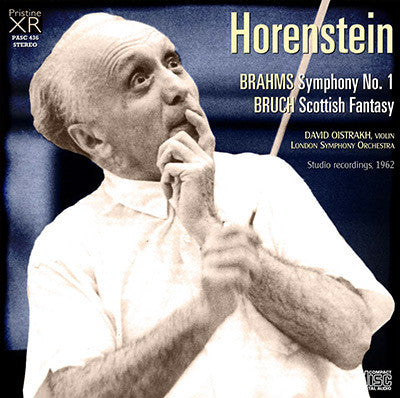

Horenstein conducts two stereo classics from 1962: Brahms and Bruch

"A profoundly impressive account of Brahms's First Symphony"

"The performance of the Bruch is superlative"

Both of these recordings were made within a few months of each other in 1962 at the Walthamstow Assembly Rooms in north-east London. The Brahms was made for Reader's Digest and engineered by legendary Decca wizard, Kenneth Wilkinson, the Bruch for Decca without Mr. Wilkinson! They were the first two of just eight studio recordings made by Horenstein with the LSO (of the rest, all but one was recorded for Unicorn Records between 1969 and 1972). Both were excellent stereo recordings for their era and, with the lightest touch of XR remastering and minimal restoration requirements, have come up marvellously here.

-

BRAHMS Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Recording producer: Charles Gerhardt

Recording Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Recorded 29-30 January 1962

Walthamstow Assembly Hall -

BRUCH Scottish Fantasy in E flat major, Op. 46

David Oistrakh, violin

Recording producer: Erik Smith

Recording Engineer: Alan Reeve

Recorded 24 September 1962

Walthamstow Assembly Hall

London Symphony Orchestra

Jascha Horenstein, conductor

Fanfare Review

Recommended for Horenstein’s outstanding Brahms

David Oistrakh’s 1962 recording of Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy is one I’ve been familiar with for years from a London reel-to-reel tape. That tape, however, couples the Bruch with Hindemith’s 1939 Violin Concerto in a performance by Oistrakh and the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer. Something I did not know before reading Pristine’s informative online notes was that the coupling intended for the Hindemith Concerto on the original Decca LP was to have been Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante with Oistrakh on violin and Hindemith taking the viola part, but the Mozart was scrapped when Hindemith heard the playback of the tape and was so “disgusted” by his own playing that he disowned the recording. The Bruch was a last-minute substitution, which required Oistrakh to salvage from mothballs a piece he hadn’t played in years.

Perhaps that’s the reason, without knowing why, I never cared much for this hastily prepared performance of the Scottish Fantasy. The feeling I’ve always had listening to it is that for long stretches Oistrakh is on autopilot, playing the notes but without much expression. He did make another recording of the piece with Gennady Rozhdestvensky and the USSR Symphony Orchestra, coupled with a Berlioz Harold in Italy. It’s available on a Russian Revelation CD, but I haven’t heard it, nor does it appear to have been reviewed in Fanfare.

One other possible reason that Oistrakh’s Scottish Fantasy is not a favorite can be summed up in one word: Heifetz. He made rather a specialty of the piece, claiming it to be his favorite “concerto,” and even I, not Heifetz’s biggest fan, have to admit that his 1947 recording with William Steinberg and the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra, and his later 1961 recording with Malcolm Sargent and the New Symphony Orchestra, are possibly unmatched for searing emotional intensity by any other violinist, save perhaps for Michael Rabin in his 1957 recording with Adrian Boult and the Philharmonia Orchestra.

Most of the Pristine releases I’ve received for review have been recordings dating from the early days of LP and some going back even further to the 78-rpm era, all subjected to Andrew Rose’s amazing XR restoring and remastering technology that has revitalized much important historical material. In this case, the Scottish Fantasy and the Brahms Symphony No. 1, both led by Jascha Horenstein, are products of the modern analog LP era. Both were recorded in 1962, both in stereo, and both had already been digitized and transferred to CD before these Pristine refurbishments—the Oistrakh Bruch, coupled with the Hindemith, exactly as on my reel-to-reel tape, and Horenstein’s LSO Brahms on a Chesky CD coupled with the Bacchanale from Wagner’s Tannhäuser with the Royal Philharmonic and Beecham Choral Society.

As usual, Andrew Rose works wonders to clean up and improve the sound, with benefit accruing mainly to Horenstein’s Brahms. The conductor’s tempos are a bit on the slow side, and of course the first-movement exposition repeat is skipped, but there’s an elemental power to the performance that can’t be denied, and the remastering makes that manifest with clarified textures and the highlighting of instruments, particularly the timpani, within those textures. The solo flute, too, towards the end of the slow introduction in the last movement, sings with a sweetness and luminosity of tone that would make the angels envious.

Rose’s rationale for rejuvenating Horenstein’s LSO Brahms No. 1 was well considered, as the performance is quite a commanding one, and the extra measure of information extracted from the original recording attests to its excellence.

With regard to the Oistrakh Bruch, I’m somewhat less positive. I’ve not heard the Decca CD, but comparing this Pristine version against my London reel-to-reel tape, I can’t say I hear much difference; and, in any case, whatever sonic improvement there may be, it doesn’t profit Oistrakh’s performance.

Recommended, then, for Horenstein’s outstanding Brahms.

Jerry Dubins

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:1 (Sept/Oct 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.