This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

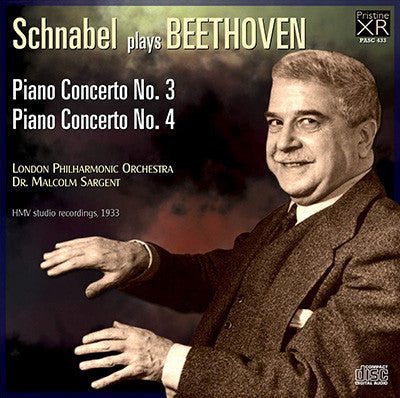

Artur Schnabel masterful in Beethoven's Concertos

"Pristine Audio’s remastering of the Third Concerto wins, hands down, for tonal solidity and presence" - Fanfare

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37

Recorded 17 February 1933

Issued October 1933 as DB.1940-44

Matrix Nos. 2B.4140-48

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58

Recorded 16 February 1933

Issued May 1933 as DB.1886-89

Matrix Nos. 2B.4132-39

Recorded at Abbey Road, Studio 1

Producer: Walter Legge

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Dr. Malcolm Sargent, conductor

Artur Schnabel piano

Fanfare Review

The orchestral sound is more forward, and, to my ear, the piano sound is more true, more solid...

Between 1932 and 1935, Schnabel and this conductor (then described as “Dr.” Malcolm Sargent) recorded the five Beethoven concertos with the London Symphony and London Philharmonic—the latter orchestra being their collaborators on February 16–17, 1933 when the Fourth Concerto was recorded the first day, and the Third on the next. Abbey Road Studio 1 was the recording venue. I had always understood that veteran producer Fred Gaisberg was responsible for Schnabel’s pre-war London sessions, but Andrew Rose credits Walter Legge with these, and it may well be, Legge having begun his career with EMI about a year earlier. The Fourth Concerto was in the stores by April, and the Third before the end of the year. They have seldom been out of the catalogs since.

Schnabel was not without recorded competition in those pre-war years. Gieseking recorded several of the concertos, Marguerite Long and Weingartner produced a rather distinctive Third, and there were a number of others. But Schnabel’s discs had a cachet of authority; even his critics could not ignore his stature as a Beethoven scholar as well as performer, his editions of the sonatas, and his concertizing. He and Sargent had first played the two works at hand in London as early as 1929.

Pristine Audio issued the Fifth, the “Emperor” Concerto, recorded in 1932, about a decade ago, and then redid it a couple of years later. Now Pristine has turned its XR technology to the two preceding works, and one hopes the first two works in the series will follow in due course. Rose gives generous credit to Keith Hardwick’s well known remasterings for EMI, which were issued in the U.S. on the Arabesque label. My copies of those discs still sound remarkably well on any machine in the house. Rose speculates that vinyl masters were made for Hardwick from the stampers, thus reducing surface noise before the digitizing process began. It made Pristine’s work all the easier, and remarkable results have been achieved.

The orchestral sound is more forward, and, to my ear, the piano sound is more true, more solid. Most important, and I suppose this involves some remixing, the total blend is better, the sound of piano and orchestra together is better balanced and more realistic. Enhanced clarity also makes the sound of the piano stand out more in passages where that is inherent in the writing. The orchestral timbre is more natural and solidity is enhanced. Good as are the Arabesque CDs, which have served me well for so long, the Pristine Audio disc is clearly superior.

As to the performances, they have been discussed by every commentator, beginning before my birth. Mortimer H. Frank and Howard Kornblum commenting on concertos Three, Four, and Five in Fanfare 5:5, 6:1, 13:4, and 15:3, inter alia, note the superiority of Schnabel’s London recordings. Frank’s term is “first and most commanding.” Since the Editor offers me a bit of space, I will add a few thoughts.

While I generally agree that the pre-war concerto recordings provide us Schnabel at his recorded best, I do not disdain his later studio performances. Strangely, he never returned to the First Concerto (nor did RCA in the U.S. ever record Rachmaninoff in the piece which was his constant calling card with orchestra when not playing his own music). Schnabel recorded the Fourth and Fifth twice more, and the Second and Third concertos once again.

The Fourth and Fifth were recorded in July 1942 in Chicago for RCA with Stock and the CSO. I am fond of both performances, particularly the Fifth. The Fourth has many felicities as well. Irving Kolodin waspishly observed (I paraphrase) that the Fifth was more successful because it did not challenge Stock’s sense of fitness in Beethoven to the extent the Fourth did. And it is true this Fourth has a bit less lyric flow than in the earlier recording under consideration here. However, interpretation and pianism are not all that different. Schnabel’s final “go” at the Fourth in the studio was definitely produced by Legge, June 5 and 7, 1946, once again in Studio 1 at Abbey Road. The distinguished Russian conductor Issay Dobrowen and Legge’s Philharmonia were on hand. I do not get a great sense of comfort and collaboration from this recording. Yet, on June 6 the same artists recorded a lovely performance of the Second Concerto. Maybe they should not have returned to the Fourth the next day, but left well enough alone.

In 1947, Schnabel returned to Abbey Road to record the “Emperor” and the Third; again, Legge was in charge, with the Philharmonia led by Galliera. The Testament reissue of the Third Concerto claims Dobrowen is again the conductor, but Schwarzkopf’s devoir to Legge, her husband, ON and OFF the RECORD, indicates Galliera conducted on May 30 as he had earlier in the week for the “Emperor.” I would bet that to have been the case. This recorded performance is an attractive one, and as with the remake of the Second, approaches the Sargent recording in performance quality. What the Testament CD cannot offer, however, is sonic appeal. It is rather recessed. Pristine Audio’s remastering of the earlier Third Concerto wins, hands down, for tonal solidity and presence.

This Pristine Audio release simply strengthens the recommendations of Frank and Kornblum writing in Fanfare long ago. Despite the undoubted interpretive interest and musical appeal of Schnabel’s later Beethoven concerto recordings, heard in optimum sonics, the 1930s recordings retain pride of place.

James Forrest

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:6 (July/Aug 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.