This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

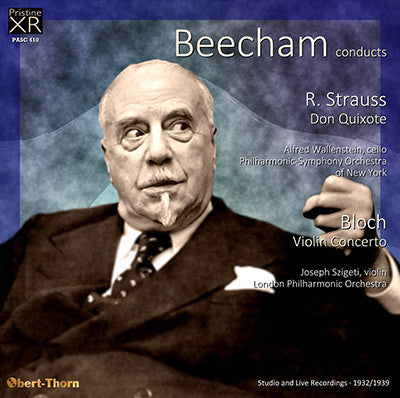

Sir Thomas Beecham conducts Strauss and Bloch - world première recordings

Rare recorded outings of Beecham conducting his contemporaries

Beecham is heard here conducting the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York, an ensemble with which he had first appeared four years earlier along with another debutant, Vladimir Horowitz, in a notorious performance of the Tchaikovsky B-flat minor concerto which saw the two taking divergent interpretive paths. Apparently, he had no similar difficulties working with the orchestra’s first desk players, which included future conductor Alfred Wallenstein handling the pivotal cello part. The recording is rather curiously balanced, with the brass and winds seeming to overpower the strings, and Wallenstein sounding rather recessed – probably playing in his usual place in the orchestra rather than up front. This recording was simultaneously made for Victor’s Program Transcription series, an early attempt at long-playing records. Each 33 1/3 rpm side was the equivalent of two 78 rpm sides, which accounts for the skipped number every third matrix.

While Beecham would go on to re-record the Strauss with his own Royal Philharmonic and Paul Tortelier as soloist fifteen years later, he never re-recorded (or indeed made an official studio recording) of the Bloch Violin Concerto, even though he had already made three classic concerto recordings with the soloist, Joseph Szigeti. Szigeti premièred the Bloch in Cleveland under Mitropoulos in December, 1938. The present recording of the first British performance with Beecham dates from the following March. Later that month, he performed and recorded it in Paris with Munch, and followed up with a further broadcast under Mengelberg in Amsterdam that November.

While the Munch recording and Mengelberg broadcast have been reissued several times on CD, the Beecham performance has curiously been unavailable since a single American Beecham Society LP release in 1973. That transfer, which was the basis for what Andrew Rose used for his present XR restoration, filled in four gaps in the original acetates (two in the first movement, and one each in the others), each lasting about 30 seconds, with the Munch studio recording. A slight difference in sound demarcates each patch. Although some disc noise and distortion remain and the first note of the third movement is clipped, the recording is valuable not only in preserving a historic collaboration, but also in presenting an infrequent recorded instance of Sir Thomas conducting contemporary music.

Mark Obert-Thorn

R. STRAUSS Don Quixote (Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character), Op. 35

Recorded 7 April 1932 in Carnegie Hall, New York

Matrix nos.: CSHQ 71658-1, 71659-1, 71661-2, 71663-1, 71665-2, 71666-2, 71668-1, 71669-1, 71671-1 and 71672-2

First issued as Victor 7589/93 in album M-144 (USA) and as Columbia LX 186/90 (UK)

Transfer and remastering by Mark Obert-Thorn

Alfred Wallenstein, cello

René Pollain, viola

Michel Piastro, violin

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York

BLOCH Violin Concerto

Live recording, 9 March 1939 in Queen’s Hall, London

First issued on The Sir Thomas Beecham Society (USA) LP WSA-5

XR remastered in Ambient Stereo by Andrew Rose

Joseph Szigeti, violin

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Sir Thomas Beecham, conductor

Fanfare Review

A new transfer of Beecham’s 1932 recording which, apparently, was the very first recording of the work...

Sir Thomas Beecham made a celebrated studio recording of Don Quixote

in 1947/8 for HMV when his cellist was Paul Tortelier. I believe that

the latest incarnation of that recording is as part of a substantial

Beecham box that David Bennett reviewed

in 2011. When I was offered the chance to review a new transfer by

Pristine Audio of a Beecham performance of the work I assumed I would be

getting a copy of that recording; that would have given me the chance

to compare the Pristine transfer with the EMI transfer that I already

own, which is in the Great Recordings of the Century series. I mean no

disrespect whatsoever to Paul Tortelier when I say that what arrived

through my letterbox was something even more interesting. For what

Pristine offer here is a new transfer of Beecham’s 1932 recording which,

apparently, was the very first recording of the work.

At the

time he made the 1947 recording Paul Tortelier was just emerging from an

orchestral career and was seeking to establish himself as a solo

cellist – the booklet note in my copy of the EMI CD, written by the late

Lyndon Jenkins, relates the amusing and typically Beechamesque cavalier

fashion in which he came to be engaged to play the work for Beecham’s

1947 Strauss festival in London. However, even though Tortelier was not,

in 1947, an established international soloist it seems clear that

Beecham engaged him as a concerto-like soloist rather than using

principals from the orchestra, as Strauss intended. In 1932 matters were

arranged rather differently: this recording followed the composer’s

preference for the use of orchestral principals. So Beecham had the

services of Alfred Wallenstein (1898-1983) who later became a conductor

but who was at that time – since 1929 – the principal cellist of the

Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York. Joining Wallenstein on the

soloists’ roster were Michel (Mishel) Piastro (1891-1970), the

orchestra’s concertmaster from 1931 to 1943, and René Pollain who was, I

believe, the principal violist at this time.

In this

recording you won’t hear Wallenstein balanced as an up-front soloist and

Mark Obert-Thorn, who has made the transfer, suggests that he may have

been seated in his customary place in the orchestra. That seems entirely

plausible but nonetheless you can hear Wallenstein perfectly clearly

and a fine soloist he makes. Beecham’s contribution is a distinguished

one too and he – and the recording engineers of the time – make sure

that plenty of detail is audible in the often-complex textures of the

Introduction. Beecham seems to me to characterise the music well, often

with a twinkle in his eye. For instance, the sheep graze placidly in

Variation II until Quixote panics them and they scatter in confusion.

The recording can’t really do justice to ‘The Ride through the Air’ –

one longs for the amplitude of modern sound – but it’s still possible to

hear the washes of sound that Beecham gets from the orchestra, the

trumpets and horns well to the fore.

As well as a very good

Don Quixote the performance benefits from an equally good Sancho Panza

and both Wallenstein and Pollain are heard to good effect in Variation

III, ‘Dialogue of Knight and Squire’. Wallenstein plays eloquently in

Variation V, ‘The Knight’s Vigil’ and towards the end, as the Don is

dying I feel that Wallenstein conveys the world-weariness of the Don and

the pathos of the scene pretty well. Hereabouts there’s a nice

simplicity of utterance to his playing and he and Beecham bring off the

ending very successfully.

Mark Obert-Thorn has made a very

good job of the transfers. The original recording was made on

experimental 33 1/3 rpm discs, each side of which was the equivalent of

two 78 rpm sides, and these have been the source material used. I’m very

glad to have heard this historic performance.

I wish I could

be as enthusiastic about the Bloch Violin Concerto but I’m afraid that

I’ve listened to this a couple of times and it really doesn’t engage my

sympathies. That’s not the fault of the performers. Szigeti is superb

and, since he’s well to the fore in the recording it’s possible to

appreciate his virtuosity in a demanding solo role. Even more admirable

is the singing purity of his tone. A prime example of that comes in an

extended slow, reflective passage in the first movement (5:52-8:50).

Szigeti’s poetic side is also strongly in evidence in the rather

haunting slow movement. I liked this movement the best – perhaps in part

because it’s the shortest movement. The first movement, however, at

18:10, is nearly three times as long and I think it’s too extended for

its own good. In particular the cadenza (12:48-15:25) just seems to go

on and on – and to no great purpose. The opening tutti in the finale

sounds brash – how much, I wonder, is that down to the recording rather

than the music; the recording can’t really cope with the volume of this

passage and, indeed, sonically this is the most problematic movement in

the concerto. Here, as elsewhere, all the performers demonstrate

commitment to the music.

Unfortunately, despite the best

efforts of Andrew Rose there are issues with the sound in this concerto.

There’s a good deal of surface noise; in loud passages the orchestra

can sound strident; and the sound often crumbles in loud passages.

Naturally, one must make allowances given the provenance of the

recording, which was captured – off air? – from a live performance in

1939, which was the UK première of the work. Later that same month

Szigeti made a studio recording with Charles Munch. We learn from the

notes that the present recording was found to have four gaps in it, each

of about 30 seconds. Prior to the only previous release of the

recording, on a 1973 LP from the American Beecham Society, these gaps

were filled by splicing in the relevant passages from the Munch

recording. That editing was done pretty seamlessly, it seems. Andrew

Rose has used the 1973 release for his transfer.

Summing up,

this release from Pristine will be of considerable interest to Beecham’s

many admirers. The Bloch is not a piece with which one would have

associated him – did he ever return to it, I wonder? So this is an

important addition to his CD/download discography, especially for

listeners who warm to the work more than I do. The Strauss is especially

significant, I suggest, not least because this was the work’s first

recording and it’s a very good one. I’m very glad to have it sitting on

my shelves next to Beecham’s 1947 recording.

John Quinn

MusicWeb International, August 2014