This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

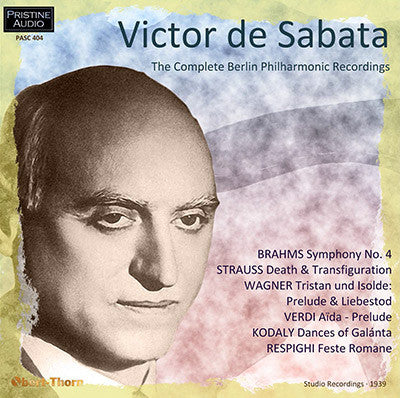

De Sabata's magnificent Berlin Philharmonic recordings together for the first time

“De Sabata’s account of the Kodaly is thrilling, and the Respighi is, quite simply, sensational: definitive.” - Gramophone, 1999

Although he would go on to record two more series of orchestral works (with the London Philharmonic in 1946 and the Santa Cecilia Orchestra in 1947-48) as well as the Requiems of Mozart and Verdi and an unsurpassed version of Puccini’s Tosca with Maria Callas, the Berlin recordings occupy a special place in his slim commercial discography. They feature uniformly superb performances – boldly conceived, rhythmically flexible and executed with tremendous verve and a minute attention to detail. Never again would de Sabata work with an ensemble of this calibre for a symphonic commercial recording session. While all of the works have appeared before on compact disc, this is the first time they have been assembled in one place (an earlier Pearl set having omitted the rare Aïda Prelude).

The sources for the transfers were yellow-label postwar DGG pressings for the Strauss, Verdi, Kodaly and Respighi items; picture-label Grammophon “Meisterklasse” pressings for the Brahms set and black-label Grammophon discs for the Wagner.

Mark Obert-Thorn

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Recorded 11, 13, 14 & 17 March 1939

Matrix nos.: 1079/80, 1057, 1061/2, 1068/9, 1059/60, 1064 & 1070 GS 9

First issued on Grammophon 67490/5s

Recorded 18 & 31 March and 6, 11 & 12 April 1939

Matrix nos.: 1107, 1072, 1108, 1074, 1097 & 1076 GS 9

First issued on Grammophon 67516/8

WAGNER Tristan und Isolde – Prelude and Liebestod

Recorded 7, 8, 11 & 12 April 1939

Matrix nos.: 1096, 1098/9, 1105/6 GS 9

First issued on Grammophon 67496/7s & 67498

VERDI Aïda – Prelude

Recorded 11 or 12 April 1939

Matrix no.: 1104 GS 9

First issued on Grammophon 68395

KODALY Dances of Galánta

Recorded 7, 8, 11 & 12 April 1939

Matrix nos.: 1100/3 GS 9

First issued on Grammophon 67525/6

RESPIGHI Feste Romane

Recorded 1, 5 & 6 April 1939

Matrix nos.: 1087/90 & 1094/6

First issued on Grammophon 67510/3s

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra · Victor de Sabata

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Special thanks to Nathan Brown and Charles Niss for providing source material

All recordings made in the Alte Jacobstrasse Studio, Berlin

Fanfare Reviews

Very enthusiastically recommended

These recordings were made by Deutsche Grammophon in Berlin in April 1939, and we would probably be better off just not to think about the political context of an Italian conductor working in Berlin in 1939, with an orchestra bereft of its Jewish players. Ironically, de Sabata’s mother was Jewish, which should have led the Nazis to ban him from the podium by 1939, and should have led him to refuse to be there!

All of that is so complicated, and would require knowledge that we (despite our clear 20–20 hindsight), don’t really have, that it is better to just concentrate on the music. After all, isn’t that what we do when we listen to the music of Wagner?

I am familiar with almost all of this material from DG LPs; only the Aida Prelude was not in the collection I owned. For those who know the recordings, the only question will be about Pristine’s sound quality, and I believe they have done some of their finest work here. The producer of the set is Mark Obert-Thorn, one of the most respected transfer engineers working today. These were never great-sounding recordings. They were not made in a good hall, but rather in a recording studio on Alte Jacobstrasse, with the lack of richness and resonance implied by that fact. In some cases, where richness of orchestral color is an essential ingredient in the music (Strauss and Respighi) this is a flaw that limits enjoyment of the performances.

But what comes through in all cases is the extraordinary conducting genius of de Sabata. Virtually all collectors know of this from his work on the first Callas Tosca, a classic that has never been out of print since its first release. Other collectors know of his fine Verdi Requiem. A handful may be familiar with Nuovo Era 013.6337, a New York Philharmonic 1951 Wagner concert performed at a remarkable level of white heat, and featuring Eileen Farrell.

Few conductors have understood as well as de Sabata does instinctively the principles of tension and release as an important element of performance. One creates that element through tempo, dynamic, and harmonic manipulation of the music. Holding back here, accelerating there, carefully grading dynamic changes and relating them to tempo changes, and emphasizing certain harmonic shifts, all of these are elements of tension and release. Overdo it and it becomes a mannerism, a tiresome trick that makes the listener feel manipulated. Underplay it and the performance fails to engage. It is that element as much as anything that underlines that EMI Tosca from beginning to end, and de Sabata not only brings that knowledge to the orchestra, but to Callas and Gobbi, and even to some extent to di Stefano as well.

Here the conductor’s mastery of dramatic progression is evident throughout, never more so than in the most dramatic (and many would say tragic) of Brahms’s symphonies. The 1939 Berlin Philharmonic was not, in fact, the great instrument it had been before it was robbed of some of its most important players, let alone that it is today. Some of the string playing is not quite in perfect unison, and can be just a touch crude. But none of that is serious enough to detract from this wonderfully free, Romantic-styled performance. If your ideal in this music is Weingartner, this is not likely to appeal. De Sabata is free with rubato, uses a wide range of dynamics, and a strong degree of portamento, though always tasteful and always very effective. His internal rhythmic pulse is unerring and firm, and this Brahms has a sense of inevitability, an inexorable momentum from beginning to end. Interestingly, the brief note included in the jewel box by Pristine quotes a 1999 Gramophone review that says: “In all these performances, the string playing is phenomenal, as is de Sabata’s way of etching phrasing and dynamics into the mind and imagination.” I agree with the second half of that sentence, but at least in the Brahms don’t quite find that unanimity in the strings that the Gramophone critic did. But please do not over-react to that reservation; it is truly a minor one when viewed against the whole.

In the Wagner, however, suddenly the strings are at a different level. The richness and beauty of sound overcomes, for the most part, the dry acoustic of the recording studio, and de Sabata’s ability to create that big arch from beginning to end, through carefully judged dynamics, so that the one true climax comes near the end of the Liebestod. Here is a perfect example of tension and release. Wagner created it in this music, and de Sabata brings it to life. The final release is not even that big climax, but rather the final chord of the Liebestod. Only then do we let our breath out. De Sabata gives us a thrilling performance of this music, one that doesn’t let up for a second.

Perhaps the biggest surprise is the Kodály. I had not heard this in years, and forgot just how lively it was, sparking with energy and rhythmic vitality, and a surprising range of orchestral color. Death and Transfiguration has many of the same qualities as the Wagner, with beautifully sustained long phrases. The performance of the Respighi is at the same level, but that is music that requires a more modern stereophonic recording.

As indicated above, Pristine’s transfer is superb, with a richness that I do not remember from the DG LPs or any prior release. Minimal notes with the disc, but more available online, and you can order this from Pristine as a download or CD. Very enthusiastically recommended.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:6 (July/Aug 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.

Thomas Beecham, the saying used to go in London, conducted “red hot.” But Victor de Sabata was “white hot.” I thought of this as I listened to Mark Obert-Thorn’s excellent sonic restorations of de Sabata’s Berlin Philharmonic recordings from 1939. The very circumstances of the performances give anyone with a capacity for irony a shiver. Here is a half-Jewish conductor, but a personal friend of Mussolini’s (and predictably scorned by Toscanini), performing with Hitler’s largely de-Semitized Berlin Philharmonic under the gimlet eye of the authorities, and getting magnificent results just before the outbreak of the Second World War.

The genius of art and political revisionism of conscience are seldom on the same page, so we do best here to leave 1930s politics alone and make only musical judgments. The more I listen to de Sabata, the more I conclude that his music making represents how the PR machine of the day suggested Toscanini was supposed to sound—but didn’t. De Sabata has the sort of fire in pressing forward that we associate with Toscanini, but not the stiffness and seeming indifference to moments of expansion that so tarnish this conductor’s presumed greatness. Reiner might be a better comparison. And Carlos Kleiber, better still. Or Solti on a very good day.

One of the compelling things about de Sabata’s Brahms Fourth is the extensive and organic use of portamento. It is a swiftish, slithery performance, and the string slides are as intuitive and natural as breathing. Portamento has now returned to modern orchestral practice, but for a long time was derided as the saccharin-sickly equivalent of “Home Sweet Home” needlepoint kitsch. But the symphony flows beautifully because of it, and the Berlin Philharmonic strings are to die for, even in 1939. This is how portamento is surely supposed to work. All these recordings are studio productions, and they unfortunately do not convey the hall reverberation we get from Willem Mengelberg’s 1939 Mahler Fourth, for example. Fortunately, the recordings are dry without being distorted. Even the tape hiss sounds smooth and bright—as easily forgotten as the rain outside. Mark Obert-Thorn at Pristine is the engineer behind the transfer, and compared to other pressings of these releases by de Sabata, such as those on the Urania label, he achieves a more natural sounding orchestral balance, largely eliminating the blatty upper midrange dominance which so dates recordings in our ears. Some things he can do nothing about. The timpani are consistently just barely audible, and in the scherzo nearly impossible to hear. This movement would be called “light,” except for the fact one that one suspects it wasn’t with a proper lower end. Obert-Thorn is a bit more conservative than Pristine’s Andrew Rose, who frequently manages to inject helpful out-of-phase material into the restoration process. Even so, this is very listenable.

To my surprise, though, I find that there exists a different restoration of the Brahms, the Strauss, and half of the Tristan music on the FONO label, remastered with the Cedar Sound System. Cedar is a British manufacturer of mixing equipment, and its restoration process evidently features the addition of reverberation. There is so much back channel information here, that one almost forgets that de Sabata’s performances are monaural, much less acoustically challenged. There are places in the Strauss where this turns slightly artificial and metallic—I would have used less—but overall, I find the added reverberation a natural and undistracting improvement.

I only wish Pristine had done something similar with the Respighi Fountains of Rome. I am not as enthusiastic as I might be about this performance, whose opening sounds rushed to me in a frantic attempt to fill out dead spots in the sound—shades of Toscanini chasing non-existent echoes in Studio 8H. But, this compilation of all the Berlin recordings under one acoustic roof is nonetheless valuable.

The Strauss and Wagner performances are as intuitively right as the Brahms. I’m particularly struck by how human the Tristan music sounds. De Sabata manages to vary the dynamics moment for moment with slight but very personal changes in mood, all the while building the sonority as we would expect. And the music arches perfectly, not just towards the great “love-death” climax, but towards the last chord itself. Compared to Karajan in both pieces, one notices that the later conductor tends to terrace his dynamics a bit portentously and make the music sound institutional and less personal.

It should be no surprise to learn that de Sabata conducts the Verdi prelude beautifully and with real power. Nor should we think the Kodály an eccentric choice: De Sabata is fully master of its compelling rhythms, if not perhaps able to convey the gorgeousness of color available on later recordings. (I’m thinking of Ormandy here).

These two CDs represent the best orchestral playing de Sabata had the good fortune to leave us as a record of his art, well collected in one place. And as usual with great conductors from the past, we are stuck with the realities of the day. Gratitude and frustration mixed together....Music, after all, is a vanishing art. Its greatest moments vanish in two seconds. And great men of the baton live or die seemingly to shadow-box the air.

Steven Kruger

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:6 (July/Aug 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.