This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

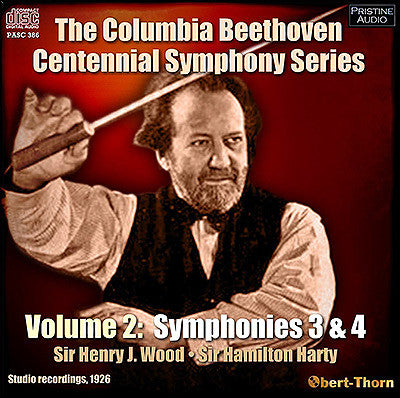

The Columbia Beethoven Centennial Symphony Series, Volume 2

Continuing this groundbreaking Symphonic series, first issued in 1927, in new Mark Obert-Thorn transfers

This volume is the second of five which will reissue, for the first time in one series, the complete symphony cycle which English Columbia commissioned to commemorate the centennial of Beethoven’s death in 1927. It was a bold move for the label, perennially in the shadow of its larger competitor, HMV, to embark on such a project at a time when no other company had recorded all nine symphonies using the relatively new electrical process. Indeed, HMV and Polydor would not complete their cycles until several years after the centennial had passed.

The first four symphonies were assigned to British conductors (Henschel, Beecham, Wood and the Northern Irish Harty) while the remainder were given to Weingartner, already generally acknowledged as a Beethoven specialist.

Henry Wood had already set down an abridged acoustic version of the Eroica for Columbia on six sides in 1922 when he was approached to record it complete for the microphone. The recording locale is not precisely known; I have seen references to both the Scala Theatre and Columbia’s Large Studio in Petty France. We do know, however, that the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra did not record it in Queen’s Hall, which was under exclusive contract to HMV at the time.

Wood’s approach is surprisingly modern for its time – fleet, unmannered, and with hardly any string portamenti to be heard. Apparently, Wood was originally intended to play a greater role in Columbia’s Beethoven Centennial series. In March of 1927, he recorded two concerti, the Emperor with Ignaz Friedman and the Violin Concerto with Albert Sammons; but neither was ever released, and the original matrices were destroyed.

The Fourth would turn out to be the only Beethoven symphony Harty recorded. His approach here is similar to Wood’s, albeit with a bit more portamenti on display, and he benefitted from the almost-too-ample acoustics of Manchester’s Free Trade Hall. For the final side (the last half of the fourth movement), the engineers must have told Harty that he was running perilously close to the four-minute maximum Columbia was apparently enforcing at the time for twelve-inch matrices, as he speeds up his already energetic reading to an exhilarating conclusion, the Hallé following him with great precision and virtuosity.

The sources for the transfers were American Columbia “Viva-Tonal” pressings for the Eroica and laminated English Columbias for the Fourth. Pitch fluctuations throughout each side, which were particularly severe in the Fourth Symphony, have been corrected in this transfer.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 3 in E flat, Op. 55 "Eroica"

Recorded 18 November and 2 and 5 December, 1926 in London

Matrix nos.: WRAX 2212/16, 2249/54, and 2262/64 (all Take 1)

First issued on Columbia L 1868 through 1874

New Queen's Hall Orchestra

Sir Henry J. Wood conductor -

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 in B flat, Op. 60

Recorded 26 – 27 November, 1926 in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix nos.: WRAX 2233-1, 2234-1, 2235-1, 2236-2, 2237-2, 2238-2, 2239-2, 2240-2, 2241-1 and 2242-2

First issued on Columbia L 1875 through 1879

The Hallé Orchestra

Sir Hamilton Harty conductor

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Additional pitch stabilisation: Andrew Rose

Special thanks to Richard Kaplan for providing source material

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Sir Henry Wood

Total duration: 73:45

Fanfare Review

A tantalizing glimpse into the musical past - listening to them has been a pleasure.

This is the second in a series of reissues of the first electrical recordings of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, originally issued in honor of the centennial of his death. Oddly, while the first four symphonies were recorded by British conductors, the rest of the recordings were by Felix Weingartner. CD reissues have reached a point of such high quality that I think it’s fair to say that most 78s and LPs have never sounded this good, since digital editing even provides the capability of removing or neutralizing faults in the originals. Of course, consumers have better equipment now than the people of 1927 had, so I’m not surprised, given the skill of the practitioners, that old recordings sound so good nowadays. Labels like Bearac, Haydn House, Klassichaus, Music & Arts (which also issues live performances), Naxos Historical, Pristine Audio, and the late, lamented Treasures from the Vault might be compared to craft beers vs. the big national breweries, and really, the big recording companies like EMI, Sony, and Universal have to consider the bottom line and the reality that many customers are not interested in old recordings and performers they may never have even heard of. Arkiv and Australian Eloquence also resuscitate old recordings but seldom reach far into the past. One striking example before I get to the actual subject. Remember Remington Records, one of the original budget labels, which existed from about 1951 to, say, 1956? Ten-inch LPs were originally $1.49 and 12-inchers, $1.99. Unlike some other budget labels, Remington did not deal in “pirate” recordings—they used real people recording under their real names and if conductors like H. Arthur Brown, George Singer, and Kurt Wöss were not exactly household words, there were also the better-known Fritz Busch, Thor Johnson, and Artur Rodzinski. Due to some problem I can’t account for, Rodzinski’s Beethoven First Symphony, his only recording for the label, was issued as being led by “Conductor X” and purchasers were invited to guess who the famous, anonymous conductor was. Thor Johnson actually made a few early stereo recordings for the company and, by that time, Remington’s LP surfaces, while not exactly quiet, did not have the sandpapery noise of its earlier releases, one of which was a Beethoven Third by Fritz Busch. When I saw that Bearac was offering a CD of the Busch (I owned the LP), I couldn’t resist ordering it, since I doubted that some guy in the suburbs of Athens had access to Remington’s master tapes and I was overcome by curiosity. It proved to be astounding—yes, there was slight surface noise but no worse than 78 transfers. I doubt that I will be astounded again and I am not astounded at how good these transfers of 1927 78s (actually recorded the year before) are.

Perhaps, influenced by the number of 78-rpm sides his recording of the “Eroica” might consume, Henry Wood sets a fast pace in the first movement and also in the finale—even the HIP crowd might approve, though they might disapprove of his omission of the first movement repeat (he observes all the subsequent ones). According to his brother, Karl, Beethoven himself was concerned that the repeat might make the symphony too long but ultimately decided it was necessary. Since Wood’s recording took up 14 sides as it is and, given the price of 78s back then (about $2.00 here) as compared to average income, I think the decision is easily justifiable—then, again, I don’t especially care about the repeat, anyway. My colleague, Richard A. Kaplan, whose 78s were used for the CD transfer, informed me that, in those days, Columbia couldn’t squeeze as much music on their 78s as Victor could, hence, Mengelberg’s Victor recording of the piece takes up 14 sides and includes the repeat. Wood’s performance exudes vigor and nervous energy. The second movement actually does sound like a march. Despite the speed, the orchestra executes the fast-moving passages well—was he using a smaller string section? In any event, Wood’s is an energetic, intense performance that, if put in the shade by later, better-recorded ones, gave the record-purchasers of the late 1920s no excuse for disliking the music. Interestingly, the producer, Mark Obert-Thorn, points out that the recording venue is unknown, but it wasn’t New Queen’s Hall, which was reserved for HMV! Just for the record, the ones I used as context references were Klemperer No. 2, Maag, Steinberg, Walter No. 2, and Fritz Busch.

I used to own Hamilton Harty’s Fourth on a budget Columbia Entre LP. Here, my context was supplied by Klemperer, Leibowitz, Maag, Monteux, and Walter No. 1. The recording sounds as if one microphone were used; it does have a certain depth—the strings are up front, the winds farther back, and the brass in the rear, but some solo wind detail gets nearly buried. A little less resonance in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall might have helped. You will hear more portamento than you’re accustomed to nowadays. He skips the first movement repeat but observes the one in the fourth movement (Leibowitz also makes this choice). I wish his slow movement were more of an Adagio; for me, it’s too brisk; on the other hand, the finale zips along at an exhilarating pace and is well executed (Leibowitz and Monteux are even a shade faster). In 1927, electrical recordings of the symphony obviously got off to a good start, though I think that subsequent 78s by Ormandy, Toscanini, and Szell received more impactful sound and are at least as good as performances. Then again, who said that these important documents need to compete with anyone’s subsequent recordings? They give us a tantalizing glimpse into the musical past. It’s hard to believe that they are 87 years old and listening to them has been a pleasure.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:1 (Sept/Oct 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.