This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Mengelberg's Tchaikovsky recalls the performance tradition of the composer

His only recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic in new Obert-Thorn transfers

The two works on this release – Mengelberg’s only recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic – came about as a result of a pair of concerts celebrating the centenary of Tchaikovsky’s birth, which were held in the Philharmonie on Friday and Saturday, July 5th and 6th, 1940. (The concerts began with the composer’s Romeo and Juliet Overture, which was not subsequently recorded.) The following Monday, Telefunken engineers took down the symphony and, the next day, the concerto.While the latter, played with Edwin Fischer pupil Conrad Hansen, was new to Mengelberg’s discography, he had previously recorded the symphony with his own Concertgebouw Orchestra (the two middle movements alone in 1927, followed by a complete recording the next year). Carried over from the earlier recording are the cuts in the last movement of the symphony, both in the development section and in the lead-up to the final peroration. Mengelberg cited the claim of Modest Tchaikovsky, the composer’s brother, that in his final performances of the work, the composer had made these cuts, wanting to tighten the structure of the movement.

The present performance differs from the earlier recording, however, in the BPO’s reticence with regard to applying string portamenti, which only really surface during the second movement of the symphony (and there, only sparingly). In addition, although the timings of the first, third and fourth movements are slightly longer in the BPO version, the second movement is over a minute longer in the 1928 Concertgebouw recording. This was probably a function of Telefunken’s desire to fit the symphony on 12 sides rather than the 13 Columbia allotted to the earlier version, which featured the second movement on four sides rather than the three given here. (Timing considerations probably also account for the elimination of most of the first movement cadenza in the concerto.)

The sources used for the transfers were German Telefunken 78s except for Side 7 of the concerto, which came from a Czech Ultraphon set.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

TCHAIKOVSKY Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 23

Recorded 9 July 1940 in the Philharmonie, Berlin

Matrix nos.: 025083-1, 025084-1, 025085-1, 25086-1, 025087-1, 025088-1, 025089 and 025090-1

First issued on Telefunken SK-3092 through 3095

Conrad Hansen piano

-

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

Recorded 8 July 1940 in the Philharmonie, Berlin

Matrix nos.: 025071-1, 025072-5, 025073-1, 025074-1, 025075-1, 025076-1, 025077-1, 025078-1,

025079-2, 025080-1, 025081-1 and 025082-1

First issued on Telefunken SK-3086 through 3091

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Willem Mengelberg conductor

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

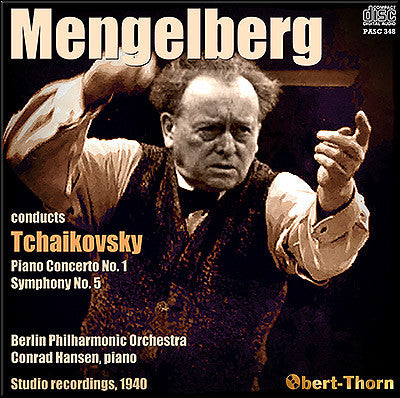

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Willem Mengelberg

Total duration: 74:29

REVIEW - Symphony No. 5

Curious to think of this being made in Hitler's Berlin just after the collapse of France, not to mention Mengelberg's Holland, in our own grim "finest hour" — and, one assumes, Germany's most exultant. How many recording sessions in London then? By July 1940 Telefunken had achieved standards in 78 recording that were never really to be surpassed. Even this dubbing, with the top cut to eliminate hiss, makes that plain, though towards the end of some of the 78 sides one detects extra congestion.

So much for the standard of recording, but it is for the interpretation of a now historic figure that this disc is valuable. Not that the sleeve-note helps at all in assessing Mengelberg. "At first it may seem difficult," we are told, "to imagine these two names (Mengelberg and Tchaikovsky) in association, the Dutch conductor whom we would sooner associate with the austere and the abstract, and in contrast the composer so vitally possessed by the Russian spirit and the sensuous experiences of life."

"The austere and the abstract"? That was certainly not the Mengelberg I remembered from his 78s, and the performance itself bears out everything I expected and could hardly belie the sleeve-note more. In its way this is about the most wilful performance of Tchaikovsky's Fifth I have ever heard. The beginning of the Allegro starts the wilfulness off. The strings set a sensible enough tempo, but the clarinet and bassoon drag everything back with a markedly slower speed. If it was one instrumentalist playing the melody, one would say the conductor had been deliberately defied. But not Mengelberg, I imagine. The next few minutes treat us to some really astonishing pulling-about, and I only marvel at the way the Berlin players manage to keep together. There is the most extraordinary effect at the ends of phrases in the first subject on the dropping octave figure, a reduction to about halftime. The rule of loud meaning fast, and soft meaning slow, can rarely have been observed more exaggeratedly either in this movement or later.

Nowadays such an approach seems very old-fashioned indeed, quaint even. But some, I imagine, will enjoy this nonetheless, for as in the Mengelberg Pathétique dubbing issued by Telefunken last year, there is the urgency and excitement of a live performance. Admittedly there is less pulling-about in the finale, but even those who like the approach are likely to be disconcerted by the two big cuts. The first is from bar 218 to 324, sizeable enough you might think. But after the great imperfect cadence and the big pause comes another major cut. The coda is taken up without warning at bar 490 on the trumpet melody "con tutta forza". I seem to remember there was similar monkeying around in Mengelberg's earlier version for Columbia with the Concertgebouw, and that took no fewer than 14 sides—four more than normal! The Telefunken originally took 12. Austere? Well, hardly.

E.G., The Gramophone, April 1963

MusicWeb International Review

It is characteristic Mengelberg: wilful, idiosyncratic, one-of-a-kind

I imagine that most readers of MusicWeb International quickly

scan the day's main headings and then, if a work or artist interests

them, jump straight to reading the review. The details of recording

dates and venues are, more often than not, I’d guess,

passed over without a great deal of attention.

To do so in this case would be to miss something of great significance,

for these recordings were made in Berlin on 8 and 9 July 1940,

replicating live performances given just a few days earlier.

In other words, less than seven weeks after the Netherlands

had suffered a bloody, unprovoked invasion, lost a campaign,

surrendered to an invading German army and been occupied by

enemy forces. That country’s pre-eminent native conductor

could be found leading the flagship German orchestra in the

capital of Nazi Europe.

Just as it does in Furtwangler's case, the controversy over

the Germanophile Mengelberg's collaboration with the Nazis remains

unresolved. Claims that he was essentially apolitical, that

he protected Jewish members of his Concertgebouw Orchestra or

that he attempted to continue promoting the banned “Jewish”

music of Mahler are all asserted. They are even more convincingly

contested for it is an incontrovertible fact that, unlike many

other conductors in Nazi-occupied countries, Mengelberg adopted

a high-profile highly supportive attitude to the new status

quo. After the war’s end he was judicially condemned as

a collaborator and his career came to an ignominious end.

As those preliminary observations indicate, these recordings

certainly have some historical/political/cultural significance.

Any inherent musical importance is, however, rather less

apparent.

The concerto can be considered - and dismissed - quite quickly.

Hansen was a competent enough pianist. He was a student of Edwin

Fischer, though it is worth pointing out that in the 1930s,

when one might have been expecting him to be pursuing a solo

career, he was just as often to be found acting as his mentor’s

teaching assistant. In all honesty, Hansen was probably out

of his depth when partnered with Mengelberg and this recording

has never been particularly highly rated, not simply because

of the soloist’s adequate though generally undistinguished

performance but also because of a horrendously cut first movement

cadenza - blamed by charitable critics on time constraints.

Perhaps a more appropriate soloist for this politically-charged

recording might have been Hitler’s favourite, the notoriously

pro-Nazi Elly Ney, who certainly had Tchaikovsky’s first

concerto in her repertoire. Indeed, she had played it at the

London Proms with Sir Henry Wood just a decade earlier, though

one imagines that, as a notorious racist and anti-semite, she

probably left the Albert Hall post-haste before the programme’s

subsequent items that included Mahler’s first symphony

and Marian Anderson singing a couple of spirituals.

What of the recording of the Tchaikovsky fifth symphony? Again,

this is not a performance for the ages. It is, though, characteristic

Mengelberg: wilful, idiosyncratic, one-of-a-kind. Not only does

the conductor impose his own tempi, dynamics and phrasings throughout

the score, but he also makes a couple of quite drastic cuts

in the finale. Interestingly enough, even though his audiences

expected - and, at that time, generally saw no great harm in

- that sort of practice, in the case of this particular symphony

Mengelberg felt compelled to justify his interventionist approach.

He claimed that Tchaikovsky’s brother Modest had told

him that the composer himself would have approved the modifications

- a suggestion that gave rise to the memorable observation,

on a later occasion when Mengelberg tinkered with Bach, that

he had presumably consulted “Modest Bach” on the

matter.

This, then, is a performance that tells us much more about interpretative

practice in the first half of the twentieth century than about

Tchaikovsky’s score. As such, it is certainly worth hearing,

but you may not want to listen to it on a regular basis and

it certainly won’t displace any of the many other fine

recorded accounts of this work.

Pristine Audio and Mark Obert-Thorn have done a sterling job

in bringing a greater degree of clarity to these 72 years old

performances than we have ever heard before. It would be a good

thing if this release were to tempt those listeners who know

him only by reputation to sample Mengelberg’s undoubted

artistry, tainted in reputation though it unfortunately remains

thanks to the conductor’s questionable wartime stance.

Rob Maynard