This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Barbirolli's mid-50s Elgar is surely among the best ever recorded

Superb Hallé orchestra in XR-remastered HMV and Mercury Living Presence recordings

These two recordings straddle the changeover from mono to stereo in the mid-1950s, and here we present the earlier recording of the Symphony No. 2 in Ambient Stereo alongside the true stereo of the Engima Variations. The latter was recorded by Mercury's legendary production team of Wilma Cozart and Harold Lawrence and is indeed a very good recording - though EMI's engineers also did a very good job. Both have been significantly improved with XR remastering. Pitching has been corrected to A=440Hz from 439.2 (Symphony 2) and 442.3 (Enigma).

Andrew Rose

-

ELGAR Symphony No. 2 in E flat major, Op. 63

Recorded 8-9 June, 1954

Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Issued as HMV ALP 1242

Presented in Ambient Stereo

-

ELGAR Variations for Orchestra on an Original Theme, "Enigma", Op. 36

Recorded 21-23 June 1956

Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Issued as Mercury MG 50125

and later in stereo as SR 90125

The Hallé Orchestra

Sir John Barbirolli conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, April 2012

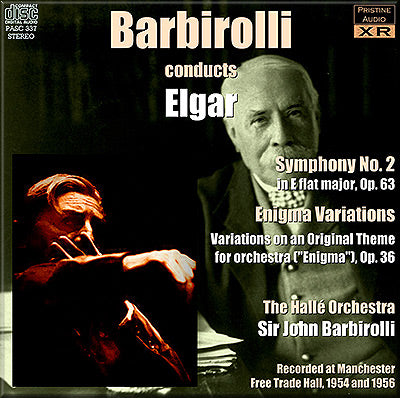

Cover artwork based on photographs of Elgar and Sir John Barbirolli

Total duration: 79:38

Review (Symphony No. 2)

For some reason few people seem to like the two Elgar symphonies equally; each has its champions and often they are more than a little bored by the rival work. I happen to be among those who have always much preferred the second, and I found listening to the two new recordings .a most pleasurable experience. I had not heard this music for some years, and found that it wears surprisingly well. I suppose that confidence and hope are among the more obvious emotions expressed by Elgar in his symphonies (in the First Symphony there seems to me to be over-confidence). But confidence and hope tend to be undermined in time of war, and the First World War and the unhappy restless years that succeeded it must have done even more to dry the springs of Elgar's creative powers than the death of his wife. He could no longer feel with sincerity the emotions he was best equipped to express.

The first movement of the Second Symphony seems to me especially endearing. As in the other movements, and indeed in Elgar's music as a whole, the tunes are all built on one rhythmic figure recurring in bar after bar, but the strong and ingenious counter-melodies with which they are adorned saves them from monotony, and the sumptuous orchestration and wonderfully engineered climaxes do the rest. For me this music sounds nsbilmente indeed, and I like it that way. Elgar told Landon Ronald (and other people too) that in the slow movement he was thinking of Edward Vii's funeral, though in fact when he began this music the king was still alive the woodwind figure in thirds represented Queen Alexandra, and the recapitulation of the first main tune (Fig. 79) the cortege passing through the crowded streets, grief expressed in the wailing oboe and shuddering string accompaniment. Certainly one can sense the passing of an age in this music. The third movement is remarkable for an episode near the end of quite shattering impact based on a tune that has already appeared unobtrusively in the first movement, while in the last serenity returns, and perhaps resignation. "Venice-Tintagel (1910-11) ", wrote the composer at the end of the score, and this is indeed strange music to have been written in Venice.

The Elgar centenary is celebrated with two magnificent recordings of this Second Symphony where before there was none; the First been available on LP since 1953. It is hard to think of any other conductors who could do as well by this music as Boult and Barbirolli. Boult's interpretation has been maturing for a quarter of a century or more. Barbirolli has come to the work only in the present decade, and his immense care and sympathy are apparent in every bar. He brings more drive and impetus to the music than Boult, and at such points as Fig. 6 in the first movement, and the fugal development in the finale (Fig. 145), the music remains exciting, whereas under Boult interest momentarily sags. On the other hand Boult comes a shade nearer the nobility of the slow movement and the tenderness of the falling tune that comes late in the development of the finale. Of the two orchestras the HalIé perhaps has a little more attack and precision. Neither has much to be proud of in the first episode of the third movement (Fig. 93-98) ; it is surprisingly difficult in quick three-eight time to play in bar after bar on the second quaver only and keep the rhythm, and the Hallé violas and 'cellos give up the attempt entirely at one point.

It is the recording quality that makes me unhesitatingly recommend the Barbirolli version. H.M.V. have really excelled themselves here. The climaxes are more exciting, and more detail comes through, while in the Nixa version there are some unhappy moments as regards intonation, notably at the start of the slow movement; these are presumably due to some form of wow" rather than to the players. I must not exaggerate these defects ; the Nixa is a good recording, but the H.M.V. is outstanding.

As a postscript I would like to mention Boult's enormous pauses in the first movement one bar after 42 and similarly near tle end of this movement. I am not sure that these quite come off, though I am aware tiat, in his later years, Elgar himself much enjoyed holding his audience in suspense by lengthening such pauses when conducting. I very much hope that one day H.M.V. will reissue Elgar's own version of this symphony. [Available here as PASC 313]

R. F., The Gramophone, July 1957

Fanfare Review

What Pristine has achieved is really quite remarkable

Well, certainly nobody disputes the pedigree of these performances. Being British myself, I have always thought foreigners have the best way with Elgar, or at least they come into it with the least baggage and delusions of wallowing, Victorian nostalgia. I have always thought, and still do even after this new disc, that Georg Solti is the basic benchmark in Elgar’s main works for orchestra, although life really isn’t complete without Toscanini’s Enigma Variations, or even Bernstein’s deranged but, against my better judgment, revelatory Elgar disc on DG. All of them dust off the cobwebs. For many John Barbirolli is the quintessential “English” conductor, with his broad North Country accent and being a fixture amid the grimy, industrial Manchester music scene. But truthfully, Glorious John is just as Italian and a tourist as Toscanini was in Elgar, although their approaches are certainly very different.

What Pristine gives us here is Barbirolli’s now rather overlooked first studio attempts at these favorite works of his. The Second Symphony was recorded for HMV in 1954 at the arse end of the mono era, whereas his first Enigma Variations is a rather trailblazing stereo experiment for Mercury/Pye, recorded only a year later. Barbirolli would in both cases get to remake them for EMI, but, as the notes rightly point out, these later and better-known versions from this gentle, affectionate musician would suffer from excessive lingering and wallowing tempi. In many ways this coupling of mono/stereo recordings represents the ultimate showcase for Pristine, whose raison d’être is Ultimate Sound Quality.

Anyone who only knows Barbirolli from his last EMI work will be caught unawares by the crusading fire of these performances. Remastered by Pristine in ambient stereo, this Second Symphony revels in its unruly, Straussian flair. Tempi are only a bit slower than Solti’s fleet-footed Decca version, and although not as tidily played as Solti’s, the Hallé orchestra sounds a damn sight less clinical. Sound is remarkable, not that the original mono as transferred on CD by EMI was unbearable. What Andrew Rose’s remastering has done is not divide the sound, but instead give the whole sound a natural sense of space and air, seemingly without losing the detail and sonic impact of the original. I still feel a bit queasy about the term “ambient stereo” (bad memories of those botched fake stereos on ’70s LPs), but in no sense does the sound feel lopsided or manipulated.

I do have a slight problem with this programming, though, as the structurally complex, impressionistic Second Symphony makes a rather messy introduction to the intricate, taut structure of the Enigma Variations. Or maybe it is because I just always prefer the confidence and form of the First Symphony. As the original Gramophone review, quoted in the notes, rightly points out, few people love each Elgar symphony equally.

Although deemed rather fast by original reviewers, Barbirolli’s Enigma sounds warm, logical, and affectionate now. Playing is relatively tidy and, although it is not short of emotion, what comes across is Barbirolli’s utter lack of artifice and cheapness. His “Nimrod” here is as sincere and soberly paced as his Mahler was. The phrasing is a delight, and only when compared to Toscanini’s extraordinary, but for some, rushed 1935 reading does one notice a slight lack of fire and forward momentum. The stereo original, not surprisingly, needs less work done on the sound, and having briefly Spotified EMI’s own transfer, it is clear that Rose has wisely not tinkered too much with what is already a vivid well-defined record.

What Pristine has achieved is really quite remarkable, giving real space yet definition to both works. Nevertheless, there is still part of me that wishes the brilliant Andrew Rose would devote his finite resources and undeniable skills to the real forgotten or unreleased recordings out there, rather than concentrate on performances most people will already have on the original company transfers. Improvements as these assuredly are, Pristine is essentially deviating from what the original company intended buyers to hear. If, however, you are unfortunate enough not to have heard Barbirolli’s first Elgar, then yes, Pristine is your first choice.

Barnaby Rayfield

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:2 (Nov/Dec 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.