This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

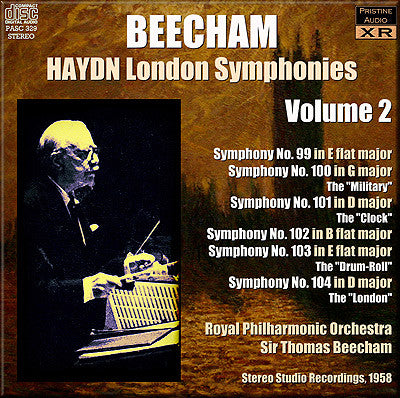

Beecham's supreme musicality exemplified in Haydn's symphonic masterworks

Second volume of six 'London' symphonies in superb stereo 32-bit XR-remastered transfers

Classical CD Review review

I highly recommend these discs

Serendipity. Some time after Wagner, audiences lost their ability to

listen to music of the Classical era. Hard to believe, but even Mozart

became

reduced to the status of a petit maître. When you accept Die

Walküre,

Tristan, or Tosca as the norm of passion, "Là ci darem la mano" seems

pretty lame. However, Mozart had his ardent champions, notably George

Bernard Shaw, who hoisted his considerable wit in the service of restoring

Mozart

to more reasonable assessment.

Haydn's reputation, however, had sunk even lower than his pupil's. A composer known in his day for his emotional force (one English writer compared him to Shakespeare) became huggable "Papa Haydn." This persisted well into the 20th century. My mother, for example, had studied music seriously during the Thirties and Forties, and I later got to read her textbooks, which characterized Haydn as "historically important" -- ie, not aesthetically important. It took the efforts of scholars like H. Robbins Landon as well as committed conductors like Sir Thomas Beecham and, later, Antal Doráti (the second to record all the symphonies; the first cycle, by Ernst Märzendorfer, had very limited release) to eventually push Haydn into standard repertory. Doráti began recording in 1969.

Companies have this weird (to me) idea that they need to re-record the same material with new artists in order to make money. Of course new artists need support, but do they really need to preserve their Beethoven's Pastorale? Will it significantly better Mengelberg's or Szell's? Why push new product with all the attendant costs of recording and editing when you already have superior inventory? I just don't get it. What results is new audiences ignorant of performance history -- the treasures and (I admit it) even some trash of the past.

Like most conductors of his era, Beecham has become a collection of anecdotes to the general classical public. I admit he left behind a superior collection of anecdotes and bon mots, but more importantly, he bequeathed a host of great performances. In many ways, he was bloody-minded, as shown by his notorious remark that "I would give the whole of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos for Massenet's Manon, and would think I had vastly profited by the exchange". He knew what he liked and stuck to it. Fortunately, he liked the unfashionable as well as the fashionable. No one, not even Barbirolli, has surpassed his Delius recordings. In the Thirties, he was one of the few to record Haydn symphonies -- and not dutifully, either, but with real brio. He had a special affinity for Handel and resurrected many forgotten works by that composer. His was, I believe, the first "complete" Messiah, although in a Modern, super-glam orchestration. Numbers that hadn't been heard in decades appeared in an "Appendix." Haydn and Beecham usually constituted an ideal match. Haydn's drollness and sentiment chimed well with Beecham's personality. He, Szell, Doráti, and Bernstein stand among my favorite Haydn conductors, although all four view Haydn differently. Szell emphasizes Haydn's elegance, Doráti his warmth, Bernstein his power, and Beecham his singing wit.

Haydn wrote six symphonies for each of his two visits to England. These so-called "London" symphonies represent the height of his art, without a dud in the dozen. They all follow the same general plan: sonata movement; slow movement; minuet and trio; rondo-like finale, often sonata rondo. Within those general specs, Haydn creates enormous variety, including monothematic sonatas, innovative, poetic orchestration, and bursts of brilliant counterpoint. Beecham does especially well in quicker movements, with a "natural" spontaneous joy and rhythmic verve to his music-making. Haydn has always been known for his musical jokes (the famous one in the "Surprise" Symphony is only one of them, and by no means the best), and Beecham seems to get them all. I especially like his second movement of No. 93, where a lacy, delicate texture rips apart with a loud fart from the bassoon, and Beecham fully commits to it. In the slow movements, Beecham shapes a complex singing line. At times, I find him a bit too slow; in one adagio, he actually put me to sleep. But I have trouble listening to slow movements anyway. I need something, in the absence of lively rhythm, to keep my attention. Beecham usually gives me an unusually interesting shaping of the musical line, a bit like a great Lieder singer.

I highly recommend these discs, although I will mention a few points that might give some listeners pause. First, he uses larger forces than we today expect. No HIP here. Second, he uses pre-Landon editions, filled with mistakes and editorial accruals that put down not what Haydn wrote, but what he should have written. Beecham doesn't observe all repeats. Third, this set appeared on the cusp of the stereo era. EMI, worried that stereo would turn out to be a fad, got into the technology late. Hence, the first six symphonies came out in mono and the second six in stereo. The difference doesn't rattle me. Beecham's sheer musicality and the spectacular playing of the Royal Phil's reeds and brasses (especially the trumpets) grandly sweep aside such objections. The very greatest performances of Haydn's symphonies are marked in large part by great solo wind players, which the Phil obviously has. Textures are full but remain clear. Finally, unless one knows the symphonies extremely well, I strongly doubt that Beecham's departures from the true text will be noticed.

The bulk of Pristine's releases are mono. The label specializes in great performances of the past and in applying the latest techniques to "wash the face" of old vinyl. This involves much more than removing crackles and pops. Here, producer Andrew Rose has digitally standardized the variations in tape recording speeds, so that pitch changes between and within movements don't jar. Apparently, he has also reduced the excessive brightness of the EMI sound of the time. Most controversially, I think, he has submitted the mono recordings to a process misleadingly called "Ambient Stereo." To me, the controversy lies exclusively in the term "stereo," rather than in the results. Based on various descriptions I Googled, unlike the notorious "electronic stereo" of the Sixties, there's no attempt to "locate" the instruments left and right. Something else happens. Mono recordings tend to sound flat and compressed forward and back, as well as left and right. Ambient Stereo rounds out the sound, or as another description has it, puts air around it. It's as if it restores the ambience of the venue, so that the sound seems to originate in an actual room rather than from a radio speaker. It's a very subtle effect. I don't listen to historical recordings because I'm so interested in history. I listen to them because I enjoy great music-making. Consequently, I think Ambient Stereo an enhancement, rather than an accretion. Pristine has decided to apply the process to its entire catalogue. More power to them.

Haydn's reputation, however, had sunk even lower than his pupil's. A composer known in his day for his emotional force (one English writer compared him to Shakespeare) became huggable "Papa Haydn." This persisted well into the 20th century. My mother, for example, had studied music seriously during the Thirties and Forties, and I later got to read her textbooks, which characterized Haydn as "historically important" -- ie, not aesthetically important. It took the efforts of scholars like H. Robbins Landon as well as committed conductors like Sir Thomas Beecham and, later, Antal Doráti (the second to record all the symphonies; the first cycle, by Ernst Märzendorfer, had very limited release) to eventually push Haydn into standard repertory. Doráti began recording in 1969.

Companies have this weird (to me) idea that they need to re-record the same material with new artists in order to make money. Of course new artists need support, but do they really need to preserve their Beethoven's Pastorale? Will it significantly better Mengelberg's or Szell's? Why push new product with all the attendant costs of recording and editing when you already have superior inventory? I just don't get it. What results is new audiences ignorant of performance history -- the treasures and (I admit it) even some trash of the past.

Like most conductors of his era, Beecham has become a collection of anecdotes to the general classical public. I admit he left behind a superior collection of anecdotes and bon mots, but more importantly, he bequeathed a host of great performances. In many ways, he was bloody-minded, as shown by his notorious remark that "I would give the whole of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos for Massenet's Manon, and would think I had vastly profited by the exchange". He knew what he liked and stuck to it. Fortunately, he liked the unfashionable as well as the fashionable. No one, not even Barbirolli, has surpassed his Delius recordings. In the Thirties, he was one of the few to record Haydn symphonies -- and not dutifully, either, but with real brio. He had a special affinity for Handel and resurrected many forgotten works by that composer. His was, I believe, the first "complete" Messiah, although in a Modern, super-glam orchestration. Numbers that hadn't been heard in decades appeared in an "Appendix." Haydn and Beecham usually constituted an ideal match. Haydn's drollness and sentiment chimed well with Beecham's personality. He, Szell, Doráti, and Bernstein stand among my favorite Haydn conductors, although all four view Haydn differently. Szell emphasizes Haydn's elegance, Doráti his warmth, Bernstein his power, and Beecham his singing wit.

Haydn wrote six symphonies for each of his two visits to England. These so-called "London" symphonies represent the height of his art, without a dud in the dozen. They all follow the same general plan: sonata movement; slow movement; minuet and trio; rondo-like finale, often sonata rondo. Within those general specs, Haydn creates enormous variety, including monothematic sonatas, innovative, poetic orchestration, and bursts of brilliant counterpoint. Beecham does especially well in quicker movements, with a "natural" spontaneous joy and rhythmic verve to his music-making. Haydn has always been known for his musical jokes (the famous one in the "Surprise" Symphony is only one of them, and by no means the best), and Beecham seems to get them all. I especially like his second movement of No. 93, where a lacy, delicate texture rips apart with a loud fart from the bassoon, and Beecham fully commits to it. In the slow movements, Beecham shapes a complex singing line. At times, I find him a bit too slow; in one adagio, he actually put me to sleep. But I have trouble listening to slow movements anyway. I need something, in the absence of lively rhythm, to keep my attention. Beecham usually gives me an unusually interesting shaping of the musical line, a bit like a great Lieder singer.

I highly recommend these discs, although I will mention a few points that might give some listeners pause. First, he uses larger forces than we today expect. No HIP here. Second, he uses pre-Landon editions, filled with mistakes and editorial accruals that put down not what Haydn wrote, but what he should have written. Beecham doesn't observe all repeats. Third, this set appeared on the cusp of the stereo era. EMI, worried that stereo would turn out to be a fad, got into the technology late. Hence, the first six symphonies came out in mono and the second six in stereo. The difference doesn't rattle me. Beecham's sheer musicality and the spectacular playing of the Royal Phil's reeds and brasses (especially the trumpets) grandly sweep aside such objections. The very greatest performances of Haydn's symphonies are marked in large part by great solo wind players, which the Phil obviously has. Textures are full but remain clear. Finally, unless one knows the symphonies extremely well, I strongly doubt that Beecham's departures from the true text will be noticed.

The bulk of Pristine's releases are mono. The label specializes in great performances of the past and in applying the latest techniques to "wash the face" of old vinyl. This involves much more than removing crackles and pops. Here, producer Andrew Rose has digitally standardized the variations in tape recording speeds, so that pitch changes between and within movements don't jar. Apparently, he has also reduced the excessive brightness of the EMI sound of the time. Most controversially, I think, he has submitted the mono recordings to a process misleadingly called "Ambient Stereo." To me, the controversy lies exclusively in the term "stereo," rather than in the results. Based on various descriptions I Googled, unlike the notorious "electronic stereo" of the Sixties, there's no attempt to "locate" the instruments left and right. Something else happens. Mono recordings tend to sound flat and compressed forward and back, as well as left and right. Ambient Stereo rounds out the sound, or as another description has it, puts air around it. It's as if it restores the ambience of the venue, so that the sound seems to originate in an actual room rather than from a radio speaker. It's a very subtle effect. I don't listen to historical recordings because I'm so interested in history. I listen to them because I enjoy great music-making. Consequently, I think Ambient Stereo an enhancement, rather than an accretion. Pristine has decided to apply the process to its entire catalogue. More power to them.

S.G.S. (August 2012)