This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

- Historic review

Clemens Krauss's mastery of Strauss evident in these radio recordings

"Krauss’s direction is ideally light and stylish. An indispensable supplement to his Decca recordings" - Fanfare

These recordings were made in the studios of Bavarian Radio for broadcast in the early 1950s, and emerged on 1960s LPs from Philips. The notes to one of these discs includes the following text: "These recording [sic.] were not made expressly for the gramophone, yet even if the recording quality does not come up to the standard of perfection one is accustomed to nowadays, it seemed well worth while rescuing them from the oblivion of radio archives, in the belief that the public will be eager to appreciate the authenticity of performances by a conductor so intimately connected with Richard Strauss."

My aim in applying modern 32-bit XR remastering techniques to these recordings, was to do away with Philips' "recording quality" caveat as much as is now possible, and I'm glad to say that in all three cases major improvements in sound quality have been achieved. Gone is the boxy, veiled tone of the originals, and in its place is a full, clear sound that would bear comparison to the finest recordings of the era.

Andrew Rose

Recorded 21 January 1953

Transfer from Philips GL 5844

Recorded 22 January 1953

Transfer from Philips GL 5843

Suite based on clavier pieces by François Couperin

Recorded 7 April 1954

Transfer from Philips GL 5843

Recorded by Bavarian Radio

Bamberg Symphony Orchestra

Clemens Krauss conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, October 2011

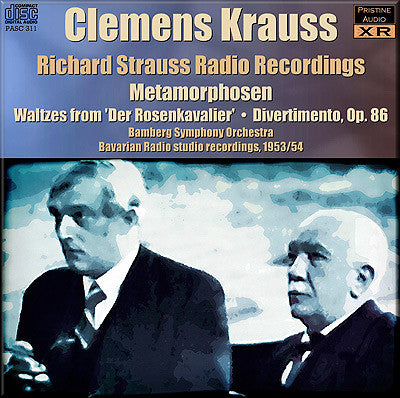

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Clemens Krauss with Richard Strauss

Total duration: 76:21

Divertimento (original sleevenotes)

Strauss' second Suite based on clavier pieces by Francois Couperin appeared as Opus 86, and entitled Divertimento.

Its very existence is due to Krauss who first performed it in Munich in

1941 as a ballet called "Verklungene Feste". A concert performance,

with Krauss conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, followed in

Vienna in 1943.

On January 4, 1941 Krauss

wrote to Strauss: "Just back from Vienna to find the first Couperin

instalment, and the second followed today. I am so glad you have

augmented the Suite for us, and I thank you with all my heart for all

the trouble you have taken over it. The scoring of the individual pieces

is absolutely masterly, and their contrasted sequence is most

effective".

Philips LP GL 5843

No Strauss devotee will need prompting from

me to acquire Clemens Krauss's interpretation of Melamorphosen. This

elegiac masterpiece came to pass after the destruction of the Munich

National Theatre by Allied bombs. Krauss at the time was the theatre's

director. There, two years earlier, he had conducted the first

performances of Capriccio. This music, therefore, spoke for him almost

as poignantly as it did for Strauss and we can feel this empathy in his

noble reading. The 1953 recording is bass-heavy and textures are not as

clearly-defined as we expect today, nor are the Bamberg strings as silky

and supple as those of the Berlin and Vienna orchestras, but they

respond to Krauss's direction with eloquence and dignity

M.K., Gramophone magazine, September 1988

Fanfare Review

Paced very naturally, clearly articulated with a full-throated vocal quality that is very involving

These two discs showcase the conductor who was, more than any other, closely identified with Richard Strauss’s music during his lifetime. The first is a selection from the extensive series he recorded with the Vienna Philharmonic for Decca in the early 1950s. These recordings have previously appeared on CD, on four Testament discs, remastered from the original tapes. For the present release, Andrew Rose has drawn on LP incarnations in Decca’s Ace of Clubs line (Don Juan) and Eclipse series from the 1970s (Also sprach Zarathustra and Till Eulenspiegel), the latter associated with the now thoroughly discredited technique of fake stereo processing, which, as Rose readily admits, was a sonic disaster. His restoration involved “negating the fake stereo (and removing any phase errors it introduced) and then re-equalizing in XR processing.” While the results thankfully undo the egregious damage inflicted by the Eclipse fake stereo, the question is how they compare with the Testament discs. Another difference is the pitch; according to Rose, “extensive frequency readings both of the music and the electrical mains hum indicate that Krauss was using a tuning of A = 449Hz, and this has been restored to the final masters.” This is fascinating, though I don’t entirely understand his reasoning and wish he’d elaborated a little more on it. It does make for a markedly sharper, brighter sound.

Questions of pitch aside, I find the new transfers a mixed success. In Also sprach Zarathustra and Till Eulenspiegel, quieter passages come across as recessed, grainy, and lacking presence; the recordings then suddenly come to life in the loud passages. In comparison, the Testament transfers consistently score higher on solidity, presence, and sense of hall acoustic. Don Juan, taken from Ace of Clubs, fares somewhat better, a pleasingly mellow sonic blend, but again lacking the impact (though also taming the early Decca “fizzy” quality) of the Testament.

As for the performances, they need little comment from me. They are classics of the gramophone, unsurpassed in their natural, idiomatic Viennese character. The orchestra had these works in its blood—virtuoso writing is dispatched with finesse and an almost insolent sense of poise and equanimity, even at the fastest tempos; ensemble is taut and trenchantly articulate; tuttis have a golden, saturated, but always transparent sound; wind solos possess a striking “speaking” quality. Fine as other conductors are in this music, with the same orchestra (including Strauss himself in 1944 [Preiser], and Decca’s later stereo series with Karajan in 1959–60), Krauss remains interpretively in a class of his own. No one brings out the heady waltz in Also sprach Zarathustra, the scherzando swagger in Don Juan, or the picaresque wit in Till Eulenspiegel quite like this.

My recommendation for these performances would remain the Testament discs. But these may be hard to find now, in which case the new Pristine will do very nicely.

No such reservations about the second disc, which gathers three recordings made in Bamberg for Bavarian Radio in 1953–54. Although not intended for commercial release, they were published in the 1960s by Philips, whose LPs have been used for the present remastering. The sound is excellent for its time and radio origin. Metamorphosen came out a few years back on Preiser, but Pristine’s transfer is preferable, slightly noisier but more open. The performance is paced very naturally, less febrile than some, clearly articulated with a full-throated vocal quality that is very involving. The string playing is totally committed, if not always as polished as some bigger-name orchestras.

The other two performances are new to me. The Rosenkavalier waltzes are dispatched with an easy authority and a memorably fruity, earthy response from the Bavarian players. The Divertimento is a real rarity, the second and lesser-known of Strauss’s two orchestral suites based on Couperin’s music. It is a substantial work of about 36 minutes, in eight movements, and drawing on 17 keyboard pieces. Strauss clearly relished the music’s harmonic and contrapuntal originality, as well as its luxuriance of embellishment. His orchestration (for chamber orchestra, including harpsichord!) is subtle and inventive, in wide-ranging reconceptions of the originals involving thickening of Couperin’s spare keyboard textures, harmonic filling out, and addition of contrapuntal lines (often with a teasing three-against-two rhythmic play). Although the Bamberg orchestra is not always flawless, Krauss’s direction is ideally light and stylish. An indispensable supplement to his Decca recordings.

Boyd Pomeroy

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:4 (Mar/Apr 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.