This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

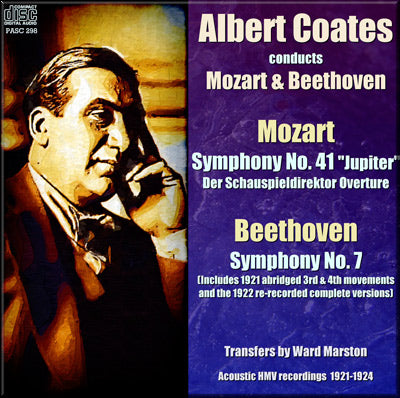

Albert Coates - complete Mozart 'Jupiter' and Beethoven 7th

Rare acoustic recordings in excellent new transfers by Ward Marston

Untangling the Beethoven Symphony No. 7 issues

For this reissue, I transferred the six sides of 1921 from the Victor issue, and the 1922 remakes of movements 3 and 4 from the French W series issue:

Movement I: 25 October 1921; (Cc589-1, Cc590-2) assigned HMV catalogue number D604 but only published on Victor 55165 and later on French HMV W437.

Movement II: 25 October 1921; (Cc591-2, Cc592-2) assigned HMV catalogue number D605 but only published on Victor 55166 and later on French HMV W438.

Movement III (abridged): 25 October 1921; (Cc593-1); assigned HMV catalogue number D606 but only published on Victor 55173.

Movement IV (abridged): 28 October 1921; (Cc605-3) assigned HMV catalogue number D606 but only published on Victor 55173.

Remakes of 3rd and 4th movements, each complete on 2 sides:

Movement III: 17 November 1922; (Cc2166-2, Cc2167-2) assigned HMV catalogue number D927 but only published on French HMV W480.

Movement IV: 17 November 1922; (Cc2168-2, Cc2169-2) assigned HMV catalogue number D928 but only published on French HMV W481.

The HMV files give assigned D series numbers to both recordings as I have indicated, but I don't think they were ever issued. The 1921 six sided version of the symphony was issued on blue label Victor 55165 55166 and 55174. In 1924, HMV planned to issue the first 2 movements from 1921, along with the remakes of the 3rd and 4th movements. It was never issued in England, but years ago, I discovered quite by accident having found a copy, that French HMV had issued it on W 437, 438, 480, and 481.

Ward Marston

-

MOZART - Symphony No. 41 in C, K.551 "JUPITER"

Recorded 27 August and 16 October 1923

Issued on HMV D942-45

-

MOZART - Der Schauspieldirektor, K486 - Overture

Recorded 22 & 24 October 1924

Issued on HMV D951-952

-

BEETHOVEN - Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92

Recorded 25 & 28 October 1921

Issued on Victor 55165, 55166, 55173

3 & 4 re-recorded 17 November 1922

Issued on French HMV W480, W481

The Symphony Orchestra

Albert Coates, conductor

(Credited to The Symphony Orchestra, probably members of London Symphony Orchestra)

Transfers by Ward Marston

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Albert Coates

Total duration: 70:41

Review of Mozart discs, 1925:

"A

correspondent has reproved me for my temerity in attributing great

virtues to symphonies of Mozart and Brahrns in a recent review. He

approves my remarks on the Mozart work, but suggests I have taken leave

of my senses in allowing that there is any beauty in the Brahms. When

his musical education has passed beyond the elementary stage he will

discover that one does notexalt one composer at the expense of another :

that one must cultivate the historical sense and understand a

composer's relation to his time, the effect of environment upon him, and

so forth finally that the whole art of music is one's kingdom and not

any one state in it. My correspondent may be surprised to learn that

there are people who regard Moz,art's music as fussy and superficial.

Here, in addition to a lack of perception, is also a lack of the

historical sense. Mozart was no revolutionary ; he adopted many of the

conventions of his time, as a study, for instance, of his piano sonatas

will prove. Even in his greatest works passages sometimes occur which

are merely eighteenth century platitudes ; but it would be ridiculous to

decry his music on that account. Appreciation, as has often been said,

is criticism ; criticism is not faultfinding, but an estimate based on a

knowledge of all the facts.

A long preamble to Mozart's

so-called Jupiter Symphony in C major—the last of the " big three " ! It

is a graceful tribute to Mozart that the premier companies have

contributed each one apiece. Let us recall the substance of what Jahn

says of these three masterpieces : " The first is a triumph of beauty in

sound, the second a work of art exhausting its topic, and the third is

in more than one respect the greatest and noblest of the symphonies."

The work we are considering is of an epic character compared to the

others ; there is an Olympian stride in the very first bars, followed by

a quietly tender passage. Here is a formula - -fortepiano—which marks

music of this century, but Mozart infuses rich life into the convention ;

on the other hand, the quickly reached dominant cadence seems as

platitudinous as Handel's descending scales ; but wait awhile. After the

pause it is a delight to follow Mozart's treatment of his theme and

recognise with joy the delicate wood-wind elaborations he contrives. The

second tune gives an opportunity for the bassoon to join in with the

first violins. A sudden outburst on a chord of C minor, after a silent

bar, is unexpected and doubtless agitated the conservatives of the

period. The music derives from the opening bars and the stress is

maintained up to the double bar, after which a repeat is made. When this

is passed Mozart gently lifts us out of the key of G into that of E

flat, extending the ideas recently heard through some enchanting

modulations and wood-wind colours. The striding figure of the opening

bars dominates the music, firmly leading it back to the recapitulation.

This time the oboe joins the bassoon and first violins in the

delineation of the second tune. The tonic and dominant end justifies

what appeared to be padding at the start, but is now heard to fit

perfectly into the scheme.

The slow movement is dramatic rather

than lyrical as the first bars suggest. In the Sturm und Drang of the

music following the flute is lost on the record, and elsewhere the same

fault occurs ; could this not be remedied 1 What Gounod called the "

divine lyricism of Mozart " appears in the second tune ; it is in thirds

on strings, bassoon, and oboe. A delicious string repartee pops up

presently and is then imitated by the flute—audible this time. The horns

are touched in with unerring instinct just before the repeat. The

weakness of the flute is apparent in the development section, where,

being occasionally overpowered by the oboe, the outline of the melody is

changed. This section has a lot of rapid string passages very well

recorded, even when the 'cellos and double basses are playing ; the

bassoons come out splendidly also.

The Minuet is well known in

arrangements, but perhaps one may draw attention to the bigness of

conception maintained here, as in the other movements of the symphony,

the exquisite shifting harmonies at the end of the Minuet, the cunning

of the trio with its oft-repeated " Amen " cadence. It was a daring

stroke to begin a section with a full close.

The finale, allegro

motto, is tremendous. Having regard to the small orchestra at Mozart's

disposal, it is amazing what a volume of sound lie must have contrived

for his musical thoughts, expressed on the largest scale. The

significance of the label "Jupiter " is best perceived here. The

movement ends with a great fugue into which are woven all the little

fragments of tunes heard before. Notice especially the one at the start,

and the assertive scalearpeggio one a little later. After a pause the

composer begins to treat his first idea semi-fugally, beginning with the

second violins. Unfortunately the 'cellos and double basses entries are

inaudible on the record. Other little bits of tunes bob up including a

jolly extension of the second idea—a flute and bassoon duet over rapid

string passages. The whole section is repeated after this. The two chief

melodies are worked in opposition, preparing the way for the fugued

finale. This, a quintuple fugue, occupies the last pages of the score

and is a reg-ular whirl of sound, an extraordinary contrapuntal feat in

which, gradually, the great Jupiter theme—the scale-arpeggio one—assumes

dominance, drives all the rest from the field, and so, ends Mozart's

farewell to the symphony. It is a magnificent gesture and we may,

listening to it, recall the composer's words in a letter to his father :

"As death, strictly speaking, is the true end and aim of our lives, I

have for the last two years made myself well acquainted with this true,

best friend of mankind, that his image no longer terrifies, but calms

and consoles me . . . I never lie down to rest without thinking that,

young as I am, before the dawn of another day I may be no more ; and yet

nobody who knows me would call me morose or discontented. For this

blessing I thank my Creator every day and wish from my heart that I

could share it with all my fellow-men." Noble, prophetic words. A man

who could write thus was already great in spirit had he never created a

note of music. But the spiritual heights revealed in this letter, allied

to such exquisite musical genius, gives us the full stature of him whom

the French composer truly called divine.

The last side is taken

up with the sparkling little overture to the Impresario. This one-act

opera was written between the Seraglio and the Marriage of Figaro. It is

an enchanting jeu d'esprit.

The recording is very good with the

exceptions alluded to above. Mr. Coates, as might be expected, stresses

the epic quality of the music ; this sometimes gives an impression of

roughness, but altogether it is a fine, vital interpretation. "

The Gramophone, January 1925