This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Scherchen's excellent Beethoven series continues

Two splendid 'fifths' performances in superb XR-remastered sound

These two recordings indicate quite powerfully the swift advances in sound quality which were obtained in orchestral recordings through the 1950s. Despite there being just three years between them, the 1951 recording of the Piano Concerto No. 5 can sound at times like it belongs to a different era when the two are compared directly.

There could be a number of reasons for this - tape technology was still in its commercial infancy, and the degree of hiss to be heard on the earlier recording is substantially higher than that of the Symphony No. 5 recording. But there is more to it than this - there is an added directness and clarity about the Symphony recording which the Concerto quite simply lacks.

The reasons for this are not too difficult to guess, and one immediately suspects both the choice and placing of the microphone(s) used to make each recording. Whilst the recording techniques used for the 1951 recording would have seemed perfectly adequate for the 78rpm era (which was still in full swing - though not for much longer), they had simply yet to address fully the technical and sonic advances offered by the new vinyl LP disc.

In short it's reasonably good for 1951, but would not have been considered good for 1954. My aim has been to ameliorate the shortcomings of the original as much as possible and to keep the overall sound as open as I could - as a result there are slightly higher levels of background tape hiss still to be heard on the Concerto recording.

This is my third restoration of my second transfer of this concerto recording - and in it I believe I was finally able to do justice to both the performance and the recording.

Meanwhile the Symphony was, comparatively speaking, a breeze - one of those wonderful recordings which almost fell off the record thanks to a combination of excellent original coupled with a superb pressing, all of which improved further with XR remastering to bring out the very best in it - a restorer's delight!

Andrew Rose

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra*

conductor Hermann Scherchen

Studio recording, Walthamstow Assembly Rooms, London, September 1954

*Recording under the pseudonym "Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of London"

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5 'Emperor' in E flat, Op. 73

Soloist Paul Badura-Skoda, piano

Played by Vienna State Opera Orchestra

conductor Hermann Scherchen

Studio recording, Vienna, June 1951

Transfers and XR remastering by Andrew Rose, January & February 2010

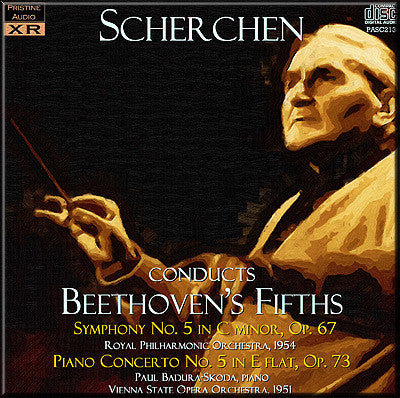

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Hermann Scherchen

Total duration: 70:37

Fanfare Review

Another winner from Pristine!

The third release in Pristine’s Scherchen Beethoven series completes the London portion of his Westminster symphony cycle. Unlike the recent Tahra edition, Pristine is supplementing the symphonies with Scherchen’s other Beethoven recordings for the label, otherwise unavailable on CD.

Scherchen’s Fifth (1954) has the same excitingly radical feel as his other symphonies with this orchestra. The first movement is lean and transparent in texture, purged of any hint of rhetorical underlinings, his refusal to indulge in any unmarked ritardandos imparting a not inappropriate ruthless feeling. Although the timing of 7:02 (with repeat) was radical in its day, it’s still around 30 seconds slower than Beethoven’s metronome marking of 108, which had to wait until the period-performance movement to be heard. Even so, the performance has a ferocious intensity rarely matched in the work’s recorded history. Despite a surprisingly measured pace (10:22), the Andante con moto maintains the tension to an unusual degree. (Among historic versions, Mengelberg [Concertgebouw, 1937/Pearl or Teldec], Toscanini [NBC, 1952/RCA], Boult [LPO, 1956/Vanguard], and Leibowitz [RPO, 1961/Scribendum] played the movement in around nine minutes; but it was Weingartner in 1932 [British SO/Naxos] who was 50 years ahead of his time at an amazingly bracing 8:36!) Scherchen, however, can use a relatively slow tempo to an unsettlingly subversive effect—there is a hungry leanness to the string lines, along with a rhythmic tautness that refuses to relax (e.g., the clipped woodwind articulation in the A-flat Minor episode, bars 167 ff., with an unusually menacing edge to it). The Scherzo is also paced deliberately (Toscanini and Leibowitz much closer to today’s norms—the latter performance an especially interesting comparison, with the RPO seven years later; although quicker than Scherchen in three movements out of four, the effect is much more streamlined, smoothing out Scherchen’s sharp edges into something far less radical). Here, Scherchen’s tempo enables a most original take on the Trio’s fugato, which is given a surprisingly lyrical, legato treatment. The transition to the finale is one of the most intense on record, in its breathtaking dynamic and rhythmic control with completely senza vibrato strings; the finale itself then erupts at a blistering half note = 92 (Beethoven’s marking is 84!). It should sound too fast, but doesn’t, thanks to Scherchen’s high-speed control and the RPO’s hairtrigger reflexes. Textures are pungent and airy—a far cry from the “saturated” sound favored by the likes of Jochum (BPO, 1951/Philips), Karajan (Philharmonia, 1954/EMI), and Furtwängler (VPO, 1954/EMI). The RPO clearly loved the ride, and its playing has an edge-of-seat excitement that is unforgettable. (Scherchen didn’t repeat the experience in his live 1965 performance with the RTSI Orchestra [Hermitage], which is much more sedate.) Among contemporary versions, Boult, Schuricht (Paris Conservatory, 1957/EMI), and most of all Szell (his earlier 1955 Cleveland version, reissued on United Archives) come closest to matching Scherchen’s punchy exuberance, even if they don’t live quite so dangerously. Altogether one of the most exceptional Fifths in the work’s recorded history, still sounding as radical as ever.

As Andrew Rose’s notes attest, the 1951 recording of the “Emperor” Concerto was always something of a problem child, afflicted by poor balances and generally well below the high standard set by the symphony cycle of a few years later. Rose’s latest transfer has worked wonders, however, and the sound is no impediment to enjoyment of a fascinating performance. Compared to his more illustrious contemporaries, Paul Badura-Skoda’s playing lacked the last degree of individuality of coloration and phrasing. Indeed his opening flourish comes across as rather pallid and under-characterized when compared to the likes of Backhaus/Krauss (Decca, 1952), Curzon/Szell (Decca, 1949), Gieseking/Karajan (EMI, 1951), Kempff/Kempen (DG, 1953), or Schnabel/Galliera (EMI, 1947/Testament). But as the movement progresses he draws us into a compellingly lyrical, if rather small-scale, interpretation, of much finesse and delicacy at quiet dynamics—e.g., in the “music box” textures in the first movement; in the second, a notable expressive variety of trills, and an uncommonly clear communication of the syncopated accenting of the quiet figuration at the end. Much of the finale has an unusual Schubertian playfulness that is quite captivating. On the other hand, sudden bravura outbursts—at the beginning of the first-movement recapitulation, and in the common (and lazy) practice of adding gratuitous bass octaves at places in the finale—tend to sound uncomfortably grafted onto the very different character of most of the performance. Scherchen’s raw, edgy vitality makes a splendid foil for the most part (those dotted rhythms in the first movement have a rare snap), though as usual the Vienna orchestra is no RPO (amusingly, the notes quote the original review in Gramophone, which took exception to the strings’ “Mahlerish” playing of the hymn-like opening of the slow movement!). Another winner from Pristine!

Boyd Pomeroy

This article originally appeared in Issue 33:6 (July/Aug 2010) of Fanfare Magazine.