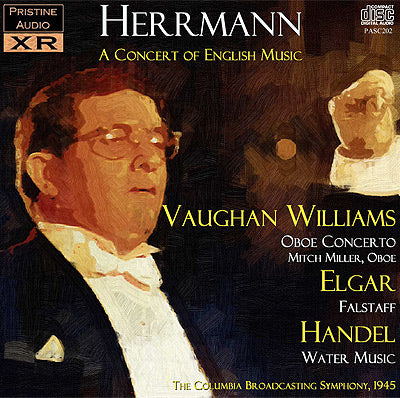

A fabulous Falstaff; Mitch Miller shines in Vaughan Williams

Superb previously unissued live broadcast recording from Anglophile Herrmann

This fascinating recording comes from the archives of

Edward Johnson. It dates from precisely one week after the surrender of

Japan brought the Second World War to an end, and in Bernard Herrmann

and Mitch Miller features two artists who would go on to become major

names in their respective fields - Herrmann as a hugely successful and

influential film composer, and Miller as one of the major movers and

shakers in the music industry. Herrmann was a passionate Anglophile,

which perhaps explains the programme here, and he and Miller had given

the US première of Vaughan Williams' Oboe Concerto three months prior to

this broadcast.

The present recording had previously been very well

dubbed onto high quality 1/4" tape from what sound like excellent

acetate discs for this era. For much of the recording the disc origin of

the recording is hard to detect, with very little surface noise.

However there are some areas where surface clicks and the occasional

swish may be detected, though these have been kept to a minimum.

The recording is technically notable for its wide

dynamic and frequency range, with a particularly well-extended treble

for this era. I have retained announcements as broadcast, as well as

including a short section of the start of the news broadcast, for

historical interest.

Andrew Rose

-

HANDEL Water Music Suite (arr. Harty)

- VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Concerto for Oboe and Strings in A minor

-

ELGAR Falstaff, Op. 68

CBS Broadcast, Sunday 9th September 1945

Introduced by Sidney Berry

Brief extract from the news read by Bern Bennett

A CBS live radio broadcast, 9th September 1945, introduced by Sidney Berry, from the archive of Edward Johnson

Transfers and XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, November 2009

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Bernard Herrmann

Total duration: 75:50

BERNARD HERRMANN

conducts English and American Music

The

death of Bernard Herrmann on Christmas Eve, 1975, in Hollywood,

deprived the film and music worlds of one of their most outspoken,

colourful and talented personalities. It is true that his choleric

personality and abrasiveness were not exactly endearing but in the words

of one who was close to him, he was like

‘

a toffee-apple, all crusty on the outside and soft on the inside’.

“

Benny,”

to his friends, was born in New York City in 1911 and showed an

interest in music at an early age. After graduating he went to New York

University and later became a student at the Juilliard School of Music.

His career took a professional turn when he went to work for the

Columbia Broadcasting System in 1933. He soon made his mark on their

radio programmes, planning them in an unconventional way and featuring

rarely heard music seldom played in public concert halls. One American

composer whom Herrmann championed for many years was Charles Ives,

several of whose works received their premieres under his direction.

|

|

Always

an ardent anglophile, Herrmann presented a great deal of English music

on the CBS network, introducing compositions by Vaughan Williams, Bax,

Delius, Cyril Scott and many others.

Indeed, when Herrmann became Conductor-in-Chief of the Columbia Symphony Orchestra in 1940,

Baker’s Musical Dictionary

noted that

he was ‘probably responsible for introducing more new works to American radio audiences than any other conductor.’

By 1948 he had also earned a chapter in David Ewen’s

Dictators of the Baton

in which the author commented on Herrmann’s ‘lack of attention to detail’ but concluded:

‘

Whatever

his faults as a conductor may be, it cannot be denied that he is a

splendid musician, that he has an enthusiasm which is found contagiously

in his performances, and that with his detestation of the stereotyped

he has been one of the most invigorating influences in the radio music

of the past two decades.'

Although

he was busy championing the music of others, he did not neglect his own

composing career and by the late 1940s several of his concert works had

received notable performances. Barbirolli had conducted his Cantata

Moby Dick

with

the New York Philharmonic in 1940 and his Symphony was performed by the

same orchestra under Howard Barlow in 1942.That same year Beecham

conducted the CBS Symphony in the suite

Welles Raises Kane

.

The Devil and Daniel Webster

Suite

was given its concert premiere by Ormandy and his Philadelphians in

1944 and was taken up by Stokowski and the New York Philharmonic in

1949.

After

the war, Herrmann made many guest appearances in British concert halls

and in 1950 completed work on his most ambitious composition, the

windswept lyric-drama

Wuthering Heights

. This was a project which had occupied him for three years and reflected his wide literary tastes.

In

1951 after the CBS Symphony Orchestra was disbanded, he spent more time

in England, where he eventually settled. In 1956 he conducted the

London Symphony Orchestra in two broadcasts, one of which included the

British premiere of Charles Ives’s

Second Symphony

(

PASC 232

)

and Elgar’s

Falstaff

,

a

particular Herrmann favourite. He considered it to be Elgar’s ‘supreme

orchestral work’ and it was one that he also performed in his CBS days (

PASC 202

).

As

time went on his public appearances became less frequent, the last of

them taking place at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in 1974, when he

conducted the Royal Philharmonic in a Byron Commemoration Concert

featuring music by Berlioz, Liszt, Richard Arnell and Elizabeth

Maconchy.

|

|

Bernard

Herrmann’s own concert works haven't really established themselves in

the regular repertoire but his name is still kept firmly in the public

eye by the many films for which he wrote the music. Quite a few of these

appear on TV from time to time and there is no doubt that it was in

this sphere of composition he was at his best.

He was introduced to the world of motion picture music by Orson Welles, for whose

Mercury Theatre Playhouse

Herrmann

had written background scores in his early CBS radio days. When Welles

moved from broadcasting to the cinema he took his Mercury Theatre

colleagues with him and made

Citizen Kane

.

This was Herrmann’s first film music assignment and it set him on a second career which he pursued to the end of his life.

One

of the most notable director/composer collaborations in cinema history

began in 1955 when Bernard Herrmann wrote the score for

The Trouble with Harry

, the first of several Alfred Hitchcock films on which he was to work. His second Hitchcock film was a splendid remake of

The Man Who Knew Too Much

and

included Herrmann’s only screen appearance. This occurs in the famous

Albert Hall sequence marking the film’s climax and featured the London

Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in Arthur Benjamin’s

Storm Clouds Cantata

, the same music that had been heard in Hitchcock’s earlier version of the story in 1934.

|

|