This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Erich Kleiber's superb 1950 Beethoven recordings

Two symphonies in two days in Amsterdam - reunited and XR remastered

These two Decca recordings were made back-to-back in Amsterdam on 8th and 9th May, 1950, and released the following year as consecutive LPs, LXT2546 and LXT2547. Since then they have both been reissued on a number of occasions, and indeed the current Decca CD issue is a faithful reproduction of the sound that Kenneth Wilkinson had managed to capture on tape on those two spring days nearly sixty years ago.

Alas, this is not necessarily a good thing, as the tone of both recordings is not particularly pleasant. Even back in April 1951, when the discs were released, the Gramophone's reviewer was easily able to put his finger on the problem: "The Eroica began with a rather acid quality, and maintained this thinness of tone throughout much of the two sides. The second side was not quite up to the standard of the first. There was good individual colouring of instruments, but bass was light, and even the drums seemed to be higher in pitch than they really are..."

Alas, a quick preview of both recordings in their current incarnation (they can be downloaded from iTunes if you want to hear them) suggests that nothing has changed - this was not a fault in the pressing, but an inherent quality of those very early Decca taped master recordings, as we found a couple of weeks ago with our survey of early Mozart symphony LP recordings, PASC151.

Although Decca were quick to resolve these issues, and went on to make some of the finest recordings of that decade, this leaves us with a series of otherwise excellent recordings from the very start of the 1950s in dire need of some tonal assistance - which means they're ideally suited for an XR-remastering makeover. Fortunately all of the basic ingredients of the recording are there - excellent microphone placement, acoustics and so forth - and one can only conjecture that something in the recording chain itself (microphones, amplifiers, tape recorders) had a far less than flat frequency response. This allows the tonal rebalance aspects of XR remastering to really do all the hard work and bring out a much fuller and more realistic sound than has previously been heard, something which is further rounded out by the application of Ambient Stereo processing, which we wholeheartedly recommend hearing.

We're also lucky here in that father Erich Kleiber takes the 7th Symphony significantly faster than his son Carlos was to a few years later, and we've been able to fit these two recordings back-to-back on this release with just over a minute to spare before hitting the 80-minute barrier of modern CD timing. At Carlos's pace this would have been impossible by a matter of some 2 or 3 minutes.

One other thing of note about this recording, again picked up first by the Gramophone reviewer, and then in an article by Edward Sackville-West, is the use of pizzicato in a section in the Allegretto of the 7th Symphony that might more often be heard arco. Here's the article which fills in the details, from May 1951:

WHEN the Concertgebouw/Kleiber LP. disc of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony was issued I pointed out that, contrary to custom, the final string phrase in the Allegretto was played pizzicato instead of arco. Dr. Kleiber has since explained to me the reason for this procedure. It appears that when he was to give his first performance of the symphony, in Berlin, he consulted the MS of the score (which happens to be in Berlin) and noticed that over the passage in question the word arco was pencilled in, but not in the composer's own hand. This suggested to Dr. Kleiber that during the original rehearsal Beethoven, seated in the body of the hall, called out to the assistant conductor "I can't hear the strings there ! "—i.e. through the wind and horns which had entered, forte, with the concluding A minor chord. It is Dr. Kleiber's conjecture that at this point the conductor himself scribbled the word arco into the score, in order to dispose of the difficulty. This ingenious explanation ignores the obvious objection that if Beethoven, who was not easy to push aside, had intended the phrase to be played pizzicato he was not likely to allow a conductor to alter his scoring. It is possible that he found the emendation an improvement, although, if we rid ourselves of all the prejudice created by innumerable hearings of the passage played arco, we shall, I think, find the persistence of the pizzicato up to the end more logical. It seems, moreover, that in the nineteenth century some great conductors (notably Hans von Billow) adhered to Beethoven's own marking. Dr. Kleiber admitted to me that although Strauss had accepted his explanation he had been unable to induce most of his eminent confreres to change the usual reading. A correspondent, however, informs me that Otto Klemperer has for many years insisted on the pizzicato ending. In the matter of the Finale, of which I had criticised Kleiber's tempo as being too slow, he objected that the tune was an Austrian folk dance and should therefore be delivered as such. But, treated symphonically, a dance tune surely ceases to be a dance, and the sense of this particular Finale does, it seems to me, demand a speed as fast as is compatible with clarity in the divisions.

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 3 'Eroica' in E flat major, Op. 55

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

The Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam

conducted by Erich Kleiber

1. Recorded 8th May, 1950, at the Grote Zaal of the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam

Issued as Decca LXT 2546, Matrix Nos: ARL 483-3A; 484-3B

2. Recorded 9th May, 1950, at the Grote Zaal of the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam.

Issued as Decca LXT 2547, Matrix Nos: 485-2B; 486-3A

Matrix nos. E2 KP 6991-1C, E2 KP 6992-1B

Transfer and XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, March 2009

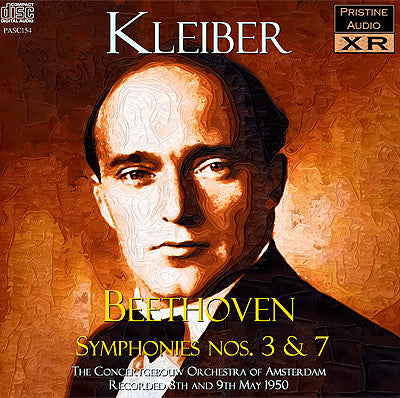

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Erich Kleiber

Total duration: 78:20

Fanfare Review

This “Eroica” is the finest historical transfer I have ever experienced.

Erich Kleiber’s 1953 Concertgebouw recordings of Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth Symphonies were regarded as instant classics, but these two 1950 Decca recordings stayed under the critical radar. Being a big fan of the Concertgebouw, then as now, I rushed out and bought both as soon as they appeared (1951). I was much disappointed by this “Eroica.” With recent Walter and Mengelberg LPs on the shelf, and Weingartner and Toscanini 78s from the college library, Kleiber seemed like weak tea. Furtwängler and Klemperer would soon bury him even deeper. Perhaps because I played it so rarely, I still have a pristine (oops!) copy of London LL 239. Pristine’s Andrew Rose had a theory: Decca had screwed up the recording, which lacked punch because it was deficient at the low end, as well as being too reverberant; he felt he could cure it by exercising his well-known magic on it. The results are sensational. The performance proves vital and thrilling after all; it is as if Mengelberg (then sequestered in his Alpine cabin) had returned and was given even better recorded sound than for his superb 1940 Telefunkens. Better yet, the Scherzo is not cut here, as it was by Telefunken, and Kleiber nails the final variations, which were the Achilles heel of Mengelberg’s performance. This is as crisp, as potent a finale as you will ever hear, with woodwind playing that outdoes even other Concertgebouw performances. The opening Allegro con brio of the “Eroica” has always been for me the summa plus ultra of all music; Kleiber now makes the finale a rival.

On the other hand, I do not possess a copy of LL 240, because I wore out two of them. I loved the Kleiber Seventh from the first moment, only later realizing that it was the Concertgebouw Seventh that was so fine, that this orchestra owned the piece. Mengelberg, Kleiber, his son Carlos, Jochum, Sawallisch (twice), Haitink—it didn’t matter who was in charge. In a review of all the recordings of all the Beethoven symphonies about 1970, the musicologist Paul Henry Lang proclaimed the Jochum/Concertgebouw Seventh to be the only completely satisfactory recording of any of the symphonies. Among other touches, this orchestra plays the fanfares that rule the finale more cleanly than any other outfit—there are four chords to each measure, not the three one usually hears. Part of the secret is not to rush it: Most performances treat the finale as a mad dash to the finish line; the Concertgebouw savors the music. I had no problem with the sound of Decca/London’s LP, because I preferred a light touch in the Seventh. If this realization is less spectacular than Rose’s “Eroica,” it is mainly because there was less wrong in the first place; perhaps he also had cleaner sources for the “Eroica”—there is less punch to his Seventh and more distortion; the bass line is stronger but not as clean as it was on the London LP. The sweet sound of the Concertgebouw is still here, too sweet for major Beethoven, perhaps, as Toscanini demonstrated with the New York Philharmonic. Mort Frank knows that I am not a fan, but there are things “The Maestro” did to perfection, and that recording heads the list. Kleiber’s first three movements now sound a bit soft by comparison, but I still like the measured tread of the finale, with its myriad of details.

I had read all of Lynn René Bayley’s encomiums of Pristine’s work on historical material with great interest, but—life being what it is—I only got to hear its stuff from the 1920s, which it at least made listenable. Now I’ve joined the club: This “Eroica” is the finest historical transfer I have ever experienced.

James H. North

This article originally appeared in Issue 33:6 (July/Aug 2010) of Fanfare Magazine.