This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Dvorak's Cello Concerto is without doubt one of the greatest of them all, with perhaps only Elgar's challenging for supremacy, and in the view of some critics is the composer's finest work, "the crowning achievement of Dvorak's copious and warm-hearted genius" according to 1955's The Record Guide.

Written in the United States through the winter of 1884-5, and then finalised with a revision of the final sixty bars some months later when the composer had returned to Bohemia, there are conflicting stories about the genesis of the Concerto, though both firmly point to American cellists as the source of Dvorak's stimulus. It is likely that the work was originally intended to have an America première, but this came to nothing when the cellist Hanus Wihan, which whom Dvorak had make a successful tour in1891-2, was refused permission to modify the solo part with his own cadenzas.

Thus the première took place in London on 19th March, 1896, with the composer conducting the Philharmonic and Leo Stern as soloist, and it would be a further nine months before the US première took place in Boston.

This Recording and its Remastering

Feuermann's Dvorak Cello Concerto was the first recording of the work in its entirety, though it was recorded on two separate sessions more than a year apart, and these recordings were issued separately. We are lucky that the first two movements were so well recorded, especially given the early date of this electric recording (the microphone method had only started to take over from acoustic horn recording some 3 years earlier).

However, the later session sounds like a technical disaster - everything the engineers got right in the first session seemed to go wrong in the second - poor treble response, excessive hiss, and just about nothing in the bass and lower mid-range below (200Hz) - just the frequencies one wishes to find with a cello recording.

This has therefore been a particularly troublesome restoration, and one which I've considered abandoning on a number of occasions as not coming up to scratch. Trying a conventional transfer and restoration of these discs is a tricky matter - to attempt to apply XR processing and bring out previously hidden frequencies whilst correcting those that are clear is exceptionally difficult, and the results are, in places, indicative of the origins of the source material.

However, on balance I decided to go ahead and issue the recording, as the overall effect of both the remastering and of Feuermann's stunning performance is simply too good to leave to one side.

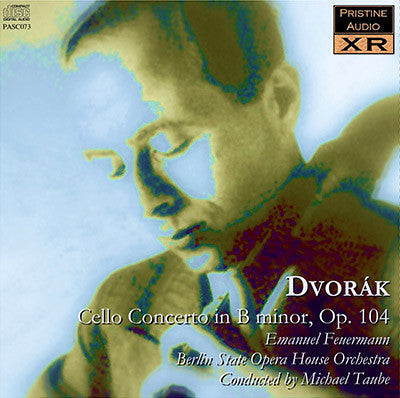

DVOŘÁK Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

Berlin State Opera Orchestra

conducted by Michael Taube

Recorded 30 April 1928 and (3rd mvt.) 27 September 1929

Transfer from UK Parlophone 78s E.10856-8 and E.11071-2

Matrix Numbers 20748-53 and 21582-4.

Transfer and Pristine Audio XR remastering by Andrew Rose, March-May 2007

Duration 33:23

Fanfare Review

This is a miraculous reconstruction

I’ve always thought it odd that this 1928–1929 Parlophone recording of the Dvořák Cello Concerto, with its boxy sound and ragged orchestral playing, is considered a classic while Feuermann’s 1940 radio broadcast conducted by Leon Barzun (once available on a Philips CD) is largely ignored. Granted, the 1940 performance has the usual problems of early-1940s broadcasts, but the sound is for the most part more natural and more uniform than on this version, and a sound wizard like Andrew Rose of Pristine Classical could, I am sure, make it a dozen times more vivid.

That being said, this is a miraculous reconstruction, especially of the third movement, which was recorded 17 months after the first two in an entirely different studio with a horrid microphone setup. The orchestra sound was tolerable, but Feuermann’s cello was grotesquely distorted, the rich, burnished tone twisted into a scratchy, bottomless whine. Mr. Rose had to make some important choices here in his restoration process, and I believe he has chosen well. By boosting certain specific bass frequencies and cutting some in treble, he has made the orchestra sound a bit odd and boxy but not too unnatural. As compensation, Feuermann’s cello sounds much more normal.

The work itself is not, to my ears, the most interesting of those for cello and orchestra, but considering the dearth of solo cello concertos it suffices as a tonal, well-loved showpiece. The conductor, Michael Taube, was a personal friend of Feuermann’s who also acted as pianist on some of his recordings, and the two are in complete musical sympathy. Of the few recordings I have heard of this work, Feuermann’s approach remains my favorite, being well inflected but less fussy than that of some other cellists.

Okay, complaint time. Thirty-three minutes is a cheesy playing time for a CD, no matter how lovingly restored. For the asking price, Mr. Rose could have included at least four more short items from the early Feuermann catalog in desperate need of his touch, namely the Bruch Kol Nidrei, Saint-Saëns’s Allegro appassionato, Granados’s Danse espagnole and David Popper’s wonderful Hungarian Rhapsody. Taken on its own terms, however, you will never hear this famous performance sound as good as it does here.

Lynn René Bayley