This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Concert Review: NY Times

This recording is the first of a collection of recordings made for Vladimir Horowitz's private use of concerts given in New York's Carnegie Hall. The recordings were captured on 78rpm acetate discs and survive in various states of disrepair in a collection held at Yale University.

I have worked from high quality transfers which had had side joins made (with various degrees of success) but no further processing or cleaning up. In the present recording the very opening arpeggiated chord comes in very slightly late as a solid rather than broken chord; otherwise everything is present.

By trimming applause I've been able to fit the main body of the concert onto a single CD; encores are available in all download versions, including the free MP3s which accompany this CD, and may be incorporated into a separate CD release in due course.

The tonal quality of the piano here is exceptional. I had to deal with some surface noise and swish, but overall this is a splendid release, only a small part of which has been previously issued.

Andrew Rose

HAYDN Piano Sonata No. 62 in E flat major, Hob. XVI:52

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro moderato (5:41)

2. 2nd mvt. - Adagio (4:28)

3. 3rd mvt. - Presto (3:55)

4. SCHUBERT Impromptu in G flat major, Op. 90 No. 3, D899 (6:47)

5. SCRIABIN Vers la flamme, Op. 72 (5:11)

6. SCRIABIN Poème in F-sharp major, Op.32 No.1 (3:09)

7. SCRIABIN Etude in F-sharp major, Op.42 No.4 (2:23)

8. SCRIABIN Etude in D-sharp minor, Op.8 No.12 (2:12)

KABALEVSKY Piano Sonata No. 3 in F major, Op. 49

9. 1st mvt. - Allegro con moto (5:41)

10. 2nd mvt. - Andante cantabile (4:37)

11. 3rd mvt. - Allegro giocoso (4:50)

12. CHOPIN Fantasie in F minor, Op.49 (12:29)

13. CHOPIN Nocturne in E minor, Op.72 No.1 (4:33)

14. CHOPIN Impromptu No.1 in A-flat major, Op.29 (3:36)

15. CHOPIN Nocturne in F-sharp major, Op.15 No.2 (3:38)

16. CHOPIN Polonaise in A-flat major, Op.53 (6:42)

Encores - Included in downloads only (NB. CD includes MP3 download of these items)

17. SCARLATTI Sonata in E major, K.380 (L.23)

18. MOSZKOWSKI Etude in A major, Op.72 No.6

19. SCHUMANN Träumerei, Op.15 No.7

20. LISZT-HOROWITZ Mendelssohn Wedding March Variations

Vladimir Horowitz piano

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

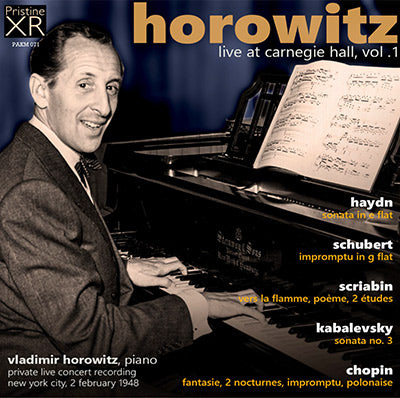

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vladimir Horowitz

Recorded 2 February 1948

Carnegie Hall, New York City

Total duration: 79:52 (CD) & 92:59 (Download)

HOROWITZ DRAWS THRONG TO RECITAL

Pianist Packs Carnegie Hall as He Offers Fine Program — Scriabin Group Heard

By OLIN DOWNES

The piano recital given by Vladimir Horowitz last night in Carnegie Hall, attended by as many as the law would allow in the place, was testimony equally to his distinguished art and to the high intelligence of his public. The program provided nothing of a spectacular character. The performances were those of a master seeking humbly and eagerly for the perfect proportion, the complete realization of the composer’s thought, and never descending to artificial effects or mere technical deeds of derring-do to astonish an audience. It may be added that this has been characteristic throughout the twenty years of appearances that Mr. Horowitz has made in America, his adopted country. With the passing of every season he has ripened and deepened as a musician, and it was as a musician and an inspired interpreter, and never merely as a spectacular virtuoso that he enjoyed last night his triumph.

He touched nothing that he failed to illumine and to give a characteristic eloquence. He began with a Haydn sonata, the one in E-flat, numbered customarily 78. This is one of the greater of the Haydn sonatas. The listener became aware that with all his eighteenth century polish Haydn was a virile musical thinker who anticipated Beethoven.

Mr. Horowitz played the adorable little G major Impromptu of Schubert — dared to play such a simple piece before such a big and possibly restless audience in an auditorium of the vastness of Carnegie Hall. He sang the long-linked melody with unfailing interest and charm, because of the variety of tone coloring and nuance that he achieved by means of his singing tone and his supremely sensitive finger-tip.

Then the pianist’s style changed completely, when he played a group of Scriabin, a composer who has rather faded from the repertory in recent years, despite his once sensational reputation. But as Mr. Horowitz played “Vers la flamme,” the F-sharp major “Poeme” of opus 32, and the two Etudes in F-sharp and D-sharp minor. Scriabin’s inflated romanticism flared or languished once more, with its original brilliancy and gorgeousness of hue. We were plunged back into the fevers of the period when Scriabin was considered the be-all and end-all of Russian piano music, and nobody who was anybody in the musical world could afford to laugh at him.

And it was realized again that after all the changes of fashions and tastes and trends in the intervening period Scriabin was a genius in his kind, no matter how unrelated he might appear to later musical progress. The harmonic boldness, the sensuousness that now leans to Wagner, now to Debussy, and Chopin too, became for the moment at least the living truth, which the interpreter resurrected by entering so deeply into the spirit of the composer.

Kabalevsky’s Third Sonata was heard on this occasion for the first time in New York, and it made an excellent impression, in spite of its indebtedness to Prokofieff and other composers and its rather curious mixture of emotional elements. There are pages of lyricism and of sportive humor, and other pages which seem dramatically and disproportionately in earnest The slow movement we like least. It is the same sort of thing that Prokofieff has done in certain slow movements — disarming, glib, mellifluous; in the case of Kabalevsky a sort of ditty in the style of a serenade — one would say with tongue in cheek. At any rate, the sonata was given a most pianistic and effective performance.

But the overwhelming performance of the evening for this writer was that of the Chopin Fantasy. We have never heard the introductory pages presented with so much imagination — the treading march in the bass, answered by the wraith-like harmonies, as if the ancestral spirits of long ago haunted the halls of the past. The molten passion of the fast movements was held magnificently in hand. The prayer that divides the dramatic pages was played with an unearthly effect, and the whisper of a pianissimo — the movement of suspense which culminates this passage — made the more startling the explosion which disperses that mood and sweeps furiously to the conclusion. With all this torrent of feeling, Mr. Horowitz maintained a classic power and balance. The interpretation of a great master!

Some were as much taken by the playing that had such grace and fantasy like a wind-blown flower, of the A-flat Impromptu. But the early composed and posthumously issued E minor Nocturne was as haunting in a different manner. Mr. Horowitz appeared rarely in the vein. The F-sharp major Nocturne and the great A-flat Polonaise brought to a fitting conclusion this concert. The audience would not move after that, and it was remaining for encores as reviewers left the hall.

The New York Times, 3 February 1948

Fanfare Review

Don’t hesitate: These are exceptional, even transcendent, releases

Starting in 1995, RCA sporadically issued a series of discs containing previously unreleased excerpts from a dozen or so concerts given by Vladimir Horowitz between 1945 and 1950. That material later reappeared, although differently organized, in Sony’s huge 42-disc Horowitz at Carnegie Hall box. Now Pristine has offered us the entirety of two of those concerts—minus most of the encores (more on that later)—giving us nearly two hours of Horowitz performances that are apparently new to the catalog.

So, how are they? In his interview in Fanfare 41:3, Pavel Gintov described Horowitz as follows: “There are artists who are very egocentric and still great: Vladimir Horowitz is one of those. He really wants to be the center of attention. You can hear him present in all music that he plays.…I don’t want to sound like I’m criticizing him. I love Horowitz, I’m just trying to say that you can always hear him playing himself. When he plays Beethoven he plays himself and when he plays Scarlatti or when he plays Chopin, he plays himself.”

If the description is hyperbolic, it’s only slightly hyperbolic, and it certainly applies to the interpretations here, where Horowitz is consistently playing himself. But what a himself! From first note to last, these are astonishing performances, and while purists and the faint of heart might find it all too much, other pianophiles will probably be transfixed. I’m not sure whether or not Horowitz reached his peak in the late 1940s, but listening to these discs will probably persuade you that he did.

Horowitz, of course, is often described (sometimes with a sneer) as a barn-burner, and there is plenty of incendiary playing here, not only in “The Great Gate of Kiev” and in the truly terrifying left-hand-octave climax of Funérailles, but in the climaxes of the Chopin First Ballade and elsewhere as well. But for every moment of unparalleled thunder, there are half a dozen others where the pianist draws the most delicate sounds from the instrument. In the ending of the first movement of the Kabalevsky Third Sonata, for instance, or the ending of the Chopin First Impromptu, there are sounds few other pianists could match. But there’s a lot more than his handling of extremes (which would have to include, besides the extremes of dynamics, his often radical rubato as well). For instance, there’s the exceptional voicing that draws unfamiliar lines from the texture, in some cases (like the first movement of the Kabalevsky) making the music sound more interesting that it really is. Then, there’s the variety of articulation. As his performance of the Chopin Fantasie makes clear, he can be not only as sharp as anyone, but also as luxurious, and the shifts from one to the other (and to numerous stages in between) keep you consistently alert. There are moments of seductive charm, too (the gracious curl of the opening of the Kabalevsky, the Scriabin Poem). There’s tremendous wit here as well, not only in the surprises that dot his extremely pianistic reading of the Haydn Sonata, but also in the giddiness of the outer sections of the Chopin Impromptu and in the ending of the Debussy Étude.

In the end, the most striking general quality is the consistent eventfulness of the performances. And nowhere is this as evident as it is in this reading of his notorious edition of Mussorgsky’s Pictures. As a teenager, under the thrall of Richter, I thought of Horowitz’s Pictures (which I knew from his studio account) as bangy. But while there certainly is plenty of sheer spectacle (and not only in the four-hand illusion of the final measures), this 1948 recording is equally notable for its interpretive invention: have the unborn chicks ever danced with more wit? Indeed, few pianists differentiate among the pictures quite as dramatically as Horowitz does. This reading, arguably even closer to the edge than his studio version or even his 1951 Carnegie Hall taping, hasn’t quite dislodged my loyalty to the Richter, but I surely wouldn’t want to be without it.

As for the encores: Pristine includes a slightly edited version of the Scarlatti Sonata that served as the first encore of the second concert (the opening measures were missing and had to be spliced from their reappearance later on), but the rest of the encores (including scorching readings of Horowitz’s version of Stars and Stripes Forever from the first concert and his Variations on the Mendelssohn Wedding March from the second) couldn’t be fit onto the already generous discs. They are included in the downloadable equivalents of these releases on the Pristine site and as free bonuses to people who buy the CDs—except in the United States, where a copyright spat has blocked all downloads of this material. Since they’re made in and shipped from France, however, the physical discs can still be purchased stateside, something that I’d urgently recommend, especially since the Sony set (and most of the RCA material) is currently hard to find, at least in CD format. The notes, as usual for Pristine, are minimal; but Andrew Rose seems to have drawn excellent sound from his sources. Don’t hesitate: These are exceptional, even transcendent, releases.

Peter J. Rabinowitz