This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

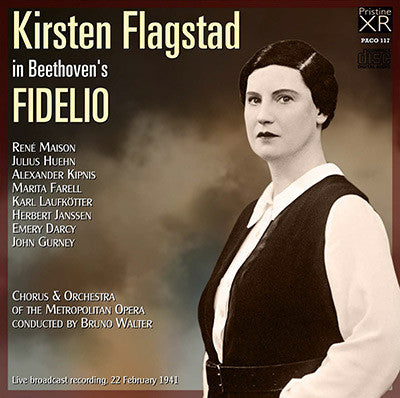

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

Flagstad and Walter's legendary 1941 Met Opera Fidelio

"Walter's inner vision is made manifest everywhere - Flagstad here delivers her best Leonore" - Gramophone, 1997

February 22, 1941 was a good day to be an opera-lover in the USA blessed with a radio and a good signal. An incredible evening in the hands of Toscanini and his NBC Symphony Orchestra, broadcasting an all-Wagner concert from Carnegie Hall with soloists Lauritz Melchior and Helen Traubel (as heard to brilliant effect on Pristine PACO 105), was merely the dessert course that followed the main meal of the day: Bruno Walter conducting Kirsten Flagstad in the Metropolitan Opera's full stage production of Beethoven's Fidelio. In the words of Mark Obert-Thorn: "Toscanini's first choice to sing Siegmund and Siegfried in his broadcast was Rene Maison; but Maison was already committed to Bruno Walter's Met Fidelio on the same day. So, the Maestro had so settle for his second choice . . . some guy named Melchior(!) It shows what a high opinion Toscanini had of Maison. (He later did get to work with him in Buenos Aires on a performance of the Beethoven 9th from the Teatro Colon in July of that year, a performance which has been issued on CD.)"

The star of the show here is of course Kirsten Flagstad, and never has she been heard so well in this performance as in this new XR-remastered edition. Taken from transfers supplied by the same (alas, anonymous) source as the Toscanini recordings of the same day, this is the full broadcast, including commentaries by Milton Cross (with sponsor messages edited), in unprecented sound quality from original acetate masters in generally excellent condition. An unforgettable experience on the night - and once again today: an all-time classic.

Andrew Rose

BEETHOVEN Fidelio, Op. 72

Leonore - Kirsten Flagstad

Florestan - René Maison

Don Pizarro - Julius Huehn

Rocco - Alexander Kipnis

Marzelline - Marita Farell

Jaquino - Karl Laufkötter

Don Fernando - Herbert Janssen

First Prisoner - Emery Darcy

Second Prisoner - John Gurney

Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera

Bruno Walter, conductor

Recorded live by NBC Radio, 22 February 1941

Metropolitan Opera, New York City

Fanfare Reviews

In Pristine Audio’s revivified sonics, a palpable sense of realism which gives the listener a “you are there” sense many thought we might never enjoy. Hear this, and be grateful.

Once again, Andrew Rose has turned his attention and audio engineering expertise to a famed operatic broadcast of the past. This performance of Beethoven’s only opera, the second in a “run” of only three, was Bruno Walter’s second performance at New York’s Met—his debut having occurred a week earlier, conducting the same work. The cast was not far removed from the previous sequence of performances, in the 1938–39 season, conducted by Artur Bodanzky, and utilizing that conductor’s sung recitatives in place of Beethoven’s spoken lines. Bodanzky had instituted his music in the 1920s and the practice continued in 1936 and 1938–39 performances featuring Flagstad, Maison, Schorr, and List. By 1941, Kipnis was available for Rocco, and Janssen for Fernando—both providing vocal balm in good measure. Sadly, however, Schorr was no longer available and his young protégé, Huehn, had taken over Pizarro. Walter, of course, restored the spoken lines.

Three years ago, in Fanfare 35:5, James A. Altena discussed this performance in depth, along with Walter’s (and Flagstad’s) other MET broadcast of the work, just over a decade later, in March 1951. The occasion was a remastered double issue by West Hill which Altena praised in the main, preferring this broadcast to the later performance.

The prime motivation for this issue seems—judging from the cover art and legend, and also the producer’s note by Rose—to have been Flagstad’s performance and a chance to remaster a set of acetates previously unavailable. This was, surely, reason enough, but I agree strongly with Altena (we are friends who do not always agree) that the real reason to listen to this broadcast and also the 1951 performance is Bruno Walter. These are his performances, stamped with his unique character, authority, and a level of drive and passion which those familiar only with his last recordings might not associate with his work. The 1941 broadcast has long been available, the most legitimate source prior to West Hill being the Met’s series of LP releases of selected broadcasts. I’ve long owned an mp3 download of that mastering. The 1951 broadcast was remastered for the Met’s Sirius broadcasts and sounds quite well in that guise. Flagstad’s 1938 broadcast with Bodanzky conducting is available on a Music & Arts release; her 1950 Salzburg performance with Furtwängler and a distinguished cast is readily available, and Walhall has issued over an hour of Walter’s 1945 Met broadcast in English with the young Regina Resnik in the title role. No one need be uncertain as to how these artists performed this music.

Thanks to Pristine’s XR sonic restoration, we can be entirely certain as to the 1941 broadcast. The clarity of the sound is remarkable and gives an accurate representation of the voices on that Saturday afternoon. Even more remarkable, the sound of Walter’s orchestra has an impact and distinctive quality not matched in the 1951 Sirius mastering.

Bruno Walter had a distinctive orchestral sound, which he seemingly carried in his hip pocket; as distinctive as Stokowski or Ormandy, and one which, he could, to at least some degree, draw from whatever orchestra he happened to be conducting. I heard all three conductors live on a number of occasions and have no doubt of this. Walter’s was a bass-heavy sonority with no fear of adding the brass into the mix. It was not heavy, but it was solid. I recall asking cellist George Neikrug, Walter’s first cello in the late-career Columbia Symphony how he did it. Neikrug shrugged and said, “He’d lift his baton and look around at the entire orchestra, and it was just there.” Listen in this new release, not only to the Fidelio and Leonore No. 3 overtures, but also to the solid underpinning of the voices in act I, in particular. No other conductor—not Furtwängler, not Toscanini, not even Knappertsbusch—brings so much emphasis to the cellos and the bass lines. And now we can really hear it. It sounds like a Walter orchestra. The orchestral playing is quite good in both 1941 and a decade later, but better in this earlier broadcast. Of course, it sounds better because of the new remastering.

The other thing I notice far more than in my mp3 transfer is how Walter cushions the voices throughout the performance. This is true in both broadcasts. (I like the 1951 broadcast much more than does Altena, but am not seeking converts.) Walter was a superior operatic conductor. We don’t have a lot, but what we have is mostly choice: his studio Wagner from the 1930s, and, in addition to the two Fidelio broadcasts, notable performances of Don Giovanni, Le nozze di Figaro, La forza del destino, and Un ballo in maschera from the Met in war-time and a 1956 English-language Magic Flute. It is fascinating, after hearing him lead Farrell (in 1941) and Nadine Connor (in 1951) through Marzelline’s act I aria, to hear how different are his emphases and even some phrasing for Frances Greer singing in English in 1945. He facilitates her breathing and articulation of the text—just one mark of great operatic conducting. There is also great Beethoven conducting here. We hear a lot of it on these CDs. It is, I think, the most intense Walter opera performance I know, matching the famous studio Walkure act I and act II excerpts with Lehmann. I find the 1951 broadcast almost as convincing in this regard (Altena does not). No two listeners hear the same way. In both performances, almost identical in their timings, Walter keeps things moving, avoiding the temptation to relax too much as the prisoners come out into the sunshine, prodding them with the orchestra back into their cells. After the prison scene the Leonore No. 3 seems to grow organically out of the closing notes of “O, namenlose Freude,” and, even more remarkable, the final scene follows the overture organically as well. The 1941 Leonore No. 3 is a white-hot performance; the later one seems even a bit faster, perhaps not quite so well controlled. In both performances, the concluding scene is not an afterthought.

In 1941 this is true, in great part, because in Herbert Janssen, Walter had one of nature’s own Ministers: a perfect match of voice (size and timbre), temperament, and musicality for the role. After an evening of beautiful singing by Flagstad and Kipnis (which we had expected), to hear a role often undercast so perfectly sung is a plus. Kipnis is in his best 1940s voice, at 50 a little beyond his prime but probably still better, vocally, than anyone else. I find him too smooth interpretively, too suave, without the blend of warmth and rusticity the role demands. But for such singing … I can endure. Similarly, although I prefer the 1951 broadcast for Flagstad’s interpretive warmth and depth of feeling, this is no doubt the best total representation of her in the role. The 1938 broadcast may be even fresher vocally, but has a few imperfections, as does this one (the improved sonics reveal a sense of strain in the highest arching lines of her great scena that I had not realized). She actually seems to negotiate some aspects of the aria better a decade later and also in the Salzburg performance. Quibbling aside, this is surely the one to have; when she tells Pizarro he must kill her to get at her husband, the tonal presence and the force of her delivery are like a spear hurled across the stage—a brilliant moment, musically, vocally, and dramatically. Flagstad first sang the role December 10, 1934 in Scandinavia, and 37 times in all. There were two performances in San Francisco, two in Switzerland, and the rest were, so far as I know, at the Met. I don’t believe she sang the opera at Covent Garden or the Colón.

Maison, who sang Florestan often in this country, at the Met, with Flagstad in San Francisco in 1937, and elsewhere, is simply not in best voice for this broadcast. I own all or nearly all of his Met broadcasts, plus performances from the Teatro Colón, and count myself a fan. He was a singer, I believe, who got up every morning not knowing for sure what the voice was going to do that day. Altena described his performance very well three years ago in these pages. At times the tone is lachrymose, almost whiny. He does improve as he goes along. He and Flagstad conclude the prison scene well and he sounds more in voice in the final scene. I do not find the young Julius Huehn adequate as the villain of the piece, however. Not only does his aria sound as though he is reading the lines; his lovely vocal timbre is all wrong for the character. Toscanini cast Janssen for the role in his 1944 broadcast with similar results, except that the German baritone knew what he was singing. Schorr’s voice was thought by some too beautiful for the role, but I find his 1938 performance pretty fine. Schöffler, at Salzburg in 1950 and the Met in 1951, is perfect, as he was years later when I saw him in the role in Los Angeles. However, in their long scene following Pizarro’s entrance aria, Huehn and Kipnis provide a satisfactory vocal blend.

Farell is an adequate Marzelline (she was better in 1938—Connor is excellent in 1951) and Laufkötter sounds old (he sounded a little younger in 1938). Darcy and Gurney are splendid prisoners—Walter always ensured good voices in those roles. (I was a child but recall Gurney as a thunderous Monterone in the late 1940s.)

Not a perfectly balanced Fidelio vocally (has there ever been such?), but very strong in some roles and extremely well led. Like so many of the “live” performances we have from the Met and other theaters in the pre- and post-World War II era, there is a frisson of excitement, and in Pristine Audio’s revivified sonics, a palpable sense of realism which gives the listener a “you are there” sense many thought we might never enjoy. Hear this, and be grateful.

James Forrest

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:6 (July/Aug 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

Back in 35:5 I reviewed in detail a previous release of this performance by WHRA (coupled with a second complete surviving broadcast Met performance of Fidelio with Walter and Flagstad from 1951), and I refer readers there for more extended commentary on its various aspects. Briefly, while noting certain shortcomings from some of the singers, I praised this as a landmark performance of interest to collectors of performances by Walter and Flagstad, and to aficionados of historic Met broadcasts. But here we have a new remastering from a previously unavailable (though unspecified) source, and the differences are sufficient to warrant not only notice of this release but some re-evaluation of the performance as well.

The big news here is Pristine’s astounding new transfer. In my previous review, I commented on “the superb remastering of Ed Wilkinson” for WHRA, in which “the astonishingly fine sound quality—often nearly equal to that of many surviving Met broadcasts from 20 years later—eclipses every other issue of this performance. The orchestra finally emerges from the dull, constricted, muddy sonics of most rival releases to sound like a real instrumental ensemble.” I have no reason to retract a word of that statement; at the time, I thought that this performance had been brought as far forward in sound quality as one might ever reasonably hope to have. But what Andrew Rose has accomplished here is simply mind-boggling, even miraculous. WHRA did indeed succeed in making the orchestra sound like a real instrumental ensemble; but compared to the depth and wealth of detail and color Rose has obtained, that issue now sounds comparatively tinny and constricted. Here, one finally gets the weighty bass line Walter favored without any muddying of the sound by artificial boosting of lower frequencies. The midrange has a newfound fullness and bloom, and the treble frequencies are enriched without any tendency toward harshness. Woodwinds now have tang and pungency; the brass, more ripeness and bite; and the strings even evince a silken tone that Walter surely brought with him from Vienna. With the entire soundstage now more forwardly placed, one does at times hear more background noise from tape hiss or acetate surfaces, and a certain dryness of the original NBC broadcast sound becomes evident; but I’ve heard surviving opera broadcasts from Italian radio sources in the 1970s with sound inferior to this 1941 performance. Rose has done some remarkable work in the past, but here he has truly outdone himself, and made the greatness of Walter’s conception of the score even more evident than before. Somehow the 13 curtain calls for Walter in his Met debut in this work eight days before seem scarcely adequate.

While the dramatic improvement in sound has less impact on the voices, it makes enough of a difference there to cause me to reassess some of my previous comments. The main beneficiary is René Maison. While noting the “rich baritonal timbre that gained him renown in several Wagnerian roles,” I previously complained of “a lachrymose distortion of the vocal line that sometimes borders on hectoring.” Now, somehow, his characterization sounds significantly more balanced, with more heroism and less hysteria, which benefits the proceedings immensely. In particular, his top notes now ring out vibrantly instead of sounding forced. Flagstad also profits from the enriched sonic profile; one now hears more dynamic shading and womanly warmth in what I previously described as a “regal voice” and “authoritative interpretation notable for its nobility and dignity,” though the occasional difficulties in her runs also become more audible as well. Julius Huehn’s Don Pizarro gains in vocal weight, and consequently in menace as well, making a fine characterization even better. Another major beneficiary is the chorus; with much improved clarity in its diction and sectional balances, it comes into its own in this performance for the first time as a noteworthy contributor to the proceedings. Kipnis (superb), Janssen (also superb), Laufkötter (passable), and Farell (poor) sound much the same as before, with the improved sonics unfortunately making the latter’s pitch problems even more painfully evident.

Another change, of lesser magnitude but one I still regard as an improvement, is that for the first time a release of this performance includes intact all of the commentary by Milton Cross, recreating for present-day listeners a sense of what it was like to actually listen to a historic Met broadcast in toto. I do wish that Rose had followed the lead of WHRA in giving the stretches of spoken dialogue their own separate tracks. That, and the lack of full booklet notes (which as usual with Pristine must be accessed on its web site) are the only and minor drawbacks of this release compared to its WHRA predecessor.

Is this performance now able to displace the Klemperer/EMI set as the front-line Fidelio for your collection? No; however, its full greatness is now finally evident. Do you still need the WHRA release? Yes, if like me you are a Walter (or Flagstad) devotee who also wants the 1951 Met Fidelio and WHRA’s typically superb documentation. Does Andrew Rose deserve a string of Penguin Rosettes here for his work on this set? Absolutely. Is this release guaranteed a slot on my 2015 Want List? You bet. This is now an essential acquisition for any collection of historic opera performances worthy of the name; emphatically and urgently recommended.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:6 (July/Aug 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.