This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

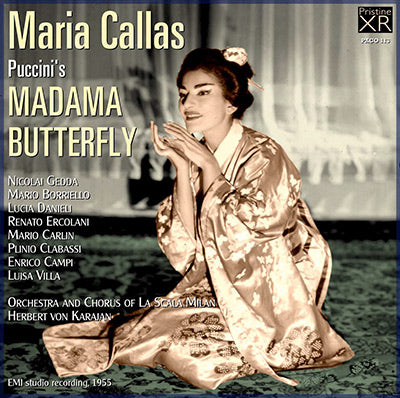

The classic Callas - Karajan Butterfly: now sounds even better!

"Callas and Karajan raise what is so often a mere tear-jerker into the deep tragedy Puccini surely intended ... the performance is quite tremendous" - The Gramophone

The 1955 Callas/Karajan EMI recording of Madama Butterfly is rightly regarded as one of the all-time classics. As the legendary Alan Blyth pointed out in his 1976 review of an LP reissue, it finds Callas at their "absolute peak of her vocal form" with taut, through-conceived support from Karajan "at every turn of the drama". However, Blyth also noted a number of technical short-comings: "recorded sound that is less than lustrous", a "confined" acoustic, "the occasional sound of studio movement" and "some momentary signs of overloading".To these I would add inconsistent tape speeds leading to drifting pitch, background rumble interspersed with accelerating traffic, and a general sense of a thin veil hanging over the sound.

All of these are as present in the most recent 24-bit Callas box set transfers as they were in 1976, or in 1955 - and each has been addressed for this new Pristine XR release. The enclosed acoustic has opened out beautifully here, with a clarity and openness that brings new life to the recording. Ambient Stereo, coupled with the lightest touch of convolution reverberation, which models the real acoustic of one of the world's foremost opera houses, adds a final sprinkle of magic to a sound that might now indeed be called "lustrous". Never has this classic Butterfly ever sounded as good!

Andrew Rose

PUCCINI Madama Butterfly

Maria Callas - Butterfly

Nicolai Gedda - Pinkerton

Mario Borriello - Sharpless

Lucia Danieli - Suzuki

Renato Ercolani - Goro

Mario Carlin - Yamadori

Plinio Clabassi - Lo zio Bonzo

Enrico Campi - Il commissario imperiale

Luisa Villa - Kate Pinkerton

Chorus and Orchestra, La Scala, Milan

Herbert von Karajan, conductor

Recorded Teatro alla Scala, Milan, 1-6 August, 1955

Producer: Walter Legge

Engineer: Robert Beckett

Originally issued as Columbia 33CX1296-8

Note: It is interesting to read these two reviews back-to-back. The initial response to this Butterfly was hardly overwhelming - but two decades later it was regarded as one of the highlights of the recorded canon.

Original LP release, 1956

We

have by now become accustomed to the idea that Maria Callas can sing

any soprano part she has a mind to, so that, though one might not

consider her a natural for the part, there is no need to be surprised

that she chose to sing Butterfly. There is, however, considerable matter

for surprise that Nicolai Gedda should have been cast for Pinkerton. It

is perfectly clear from the moment he opens his mouth that Mr. Gedda

would not hurt a flea, let alone a butterfly— and above all such an

exotic specimen as this. This considerably alters the dramatic balance

of the opera. Those parts of the score, moreover, where full and ringing

tones are needed to realise Puccini’s intentions considerably

overstrain the resources of this beautiful voice: but in other parts,

where tenderness and soft lyrical tone are needed, Mr. Gedda comes into

his own and can look any Italian tenor in the larynx! Among such

moments, which necessarily occur in the first act, since Pinkerton has

to be all out nearly all the time in the last, are his conversation with

Butterfly immediately after her entrance, and his comforting “Bimba non

piangere”, the gentle sensuousness of “Viene la sera” and “Bimba dagli

occhi ”, later on. After this it is hard going for him and he is finally

defeated when Callas is in full flood at the end of the love duet. Even

so, he is never reduced to shouting, but one does want a voice like

Stefano’s to fill out the soaring phrases with ringing tone.

Stefano

is also more in character as the brash and cynical young lieutenant who

takes his fun where he finds it, without thought for anyone but

himself.

Campora comes vocally somewhere between these two,

inclining in character much more towards Gedda’s gentier

interpretation, and, like Gedda, paying more attention to Puccini’s

expression markings than Stefano does.

We may, therefore, rate Gedda’s as a gallant performance with musical merits all too rarely found in operatic tenors.

Inghilleri

was a paternal consul in the Decca set, Gobbi an austere one in the

H.M.V,—one felt his sympathy with Butterfly was very much on the

surface, Boriello, in the new set, though without Gobbi’s vocal

opulence, I like best of all the three. His voice is of very pleasing

quality and he never misses a point: he is obviously deeply sorry for

the deserted wife.

Lucia Danieli seems also, to me, the best

Suzuki and Renato Ercolani’s the most malicious (and salacious) Goro;

but these parts were well cast in the two previous issues.

I have

written at some length before about Renata Tebaldi and Victoria de los

Angeles in the part of Butterfly and now, having heard Maria Callas and

compared her rendering with theirs my final impression, which involves

no great powers of perception, is that Tebaldi is throughout wholly in

the skin of the part and in it gives her finest performance on disc. She

alone can open out her voice to its fullest extent without loss of

quality, can command a most lovely mezza-voce—the high B at the end of

the lullaby in Act 3, for example— and can the most poignantly work on

our emotions. The only thing in her performance I regret are the stagey

outbursts of laughter, of which there are three too many. Tebaldi

sounds, admittedly, mature and Victoria de los Angeles is certainly more

of the “little child wife” and conveys greater charm. But her

beautifully sung performance, most moving where the child is concerned,

never really touched me deeply. It seems incredible that she should not

have been able to put more into the anguished words in the last act,

“Tutto é morto per me! tutto é finito ! ah!”. The way Tebaldi and Callas

enunciate that “ah” pierces the heart.

Callas gives consistently

the best sung performance I have heard from her. At her entrance she

takes the optional top D flat and the voice develops that slow beat

sometimes noticed elsewhere: but this happens on no other occasion and

she can, like Tebaldi, give a cutting edge to her tone when that is

dramatically called for.

There are some points that Callas

misses. Tebaldi’s singing of “Dolce notte! quante stelle!” brings the

scented, starlit night before us, but Callas puts nothing behind it at

all and she is, for a moment, as casual in “Un bel di”, at “Chi sara”

etc. Such moments are, however, few and the only other one worth

mentioning is when the canon is fired and she, like Los Angeles, gives

no hint of what that means to her. Tebaldi alone registers, as she quits

the high G sharp, the unbearable tension of that moment.

Callas’s

singing of “Che tua madre”, with the cry “Ait! morta” at the end, is

magnificent, and so is her outburst of joy and faith after the canon is

heard. It is wonderful, in contrast to these great outbursts, to hear

how she whitens her tone to suggest the youth of Butterfly.

The

death scene is tremendous, a generous outpouring of tone equalled only

by Tebaldi, and as the opera ends one is filled with the sense of having

heard a great performance of the part.

Erede gives the most

sensitive (and sensuous) performance of the orchestral part, Gavazzeni

the least sympathetic—his tempos are also sometimes too quick—but

Karajan, in a wholly sympathetic rendering, brings out more of the

detail of the score than I have ever heard before, in which he is aided

by the clearest and most vivid of the three recordings. The Decca set

has, unfortunately, a rather blurred orchestral part. The entrance of

Butterfly is better engineered than in the H.M.V. set, in that she does

appear to be coming nearer all the time and not suddenly.

There

is a regrettable crash, after Sharpless hints that Pinkerton may never

return, which sounds as if all the tea-trays in Japan bad been dropped:

and there are moments when the orchestral tone is rather coarse. Though

both recordings were made in the Rome Opera House, the H.M.V. acoustic

is slightly more spacious than the Columbia. Between sides 2 and 3 the

break comes at an awkward moment, just before Butterfly runs out to get

her child, and so the dramatic force of her cry “Ah! m’ha scordata” is

dissipated by the ending of the side. But these are minor faults in view

of the general excellence of this most interesting and in very many

ways splendid issue.

A. H.

The Gramophone, December 1955

Review: 1976 LP reissue

“E

un immensa pietà” (“it’s heartbreaking”), says Sharpless near the end

of Butterfly, and in the most direct sense those were my sentiments as I

listened to this set. As it progresses Callas and Karajan raise what is

so often a mere tear-jerker into the deep tragedy Puccini surely

intended, reminding us what a masterly score this is. Indeed my

well-seasoned and wary ears were quite overwhelmed by the experience. If

I knew someone who doubted the validity of opera as music-drama I would

sit him down to listen to the last twenty minutes of this set, text in

hand, to receive an object-lesson in what it is all about. From the

false happiness of “E qui, e qui!” through the stunned empty tone of

“forse potrei cader morta sull’attimo” and the expansive generosity of

“sotto il gran ponte del cielo” to the searing intensity of the suicide

and Karajan’s heartrending last chord, the performance is quite

tremendous.

But there is more, much more to Callas’s

interpretation, and I could quote enough examples of her penetrating

vision of what Butterfly means to fill the rest of the page. Let me

suggest but three: the way she suggests at “Ieri son salita tutta sola

in segrcto” (Act I) all Cio-Cio-San’s absolute faith in following her

destiny and forsaking her religion, the gentle simplicity of “Mio marito

m’lia pro- mcsso” and, a little later in Act 2, at the end of “Che tua

madre” the impending tragedy of the repeated “Mortal”. Callas made this

set when she was at the absolute peak of her vocal form, and she is the

mistress of every vocal change needed to express Butterfly’s changing

mood, even to the white, little-girl timbre she uses in the first act,

which sometimes sounds too twee; that and the sour D flat at the end of

the Entrance are my only adverse criticisms of her interpretation.

Karajan

supports Callas at every turn of the drama with a tauter, more

through-conceived direction than he brought to his recent Decca version

(SET584-6, 2/75), where the slow tempi evident here seem to my ears at

least to have turned to self-indulgence and rhythmic flabbiness, but

for once my heart was not in comparative listening. Whenever I turned

away to test reactions to other sets I longed to be back chez Callas and

Karajan, and blow recorded sound that is less than lustrous. Even, on

this occasion, my old love Scotto and Barbirolli (HMV Angel SLS927,

9/67) could not shake my new allegiance, although Scotto comes much

nearer to Callas’s very personal interpretation than does Freni, good as

she is taken in isolation too.

The young Gedda presents a

credibly un-caddish Pinkerton, an unthinking but hardly callous lover in

Act I, full of real remorse in Act 3, and always singing with fresh,

easy tone and faultless phrasing but without the ‘face’ or bright attack

of Pavarotti for Karajan’s Decca recording. Gedda is happier in the

part’s more lyrical moments. You could hardly have a more sympathetic

Sharpless than Borriello, or a more actively engaged Suzuki than Lucia

Danieli. There is the occasional sound of studio movement, some

momentary signs of overloading when Callas really lets go, for the

acoustic is confined and has not been much improved by the introduction

of electronic stereo, and there is a poor break between Sides 2 and 3,

but honestly these considerations pale before the kind of theatrical

involvement we have on all sides, and the price is very competitive

with no recommendable bargain version available.

A.B.

Gramophone, May 1976

Classical CD Review review

Andrew Rose's remastering has worked wonders on this recording made well over a half century ago

This 1953 [sic] EMI recording of Puccini's Madame Butterfly is

considered to be legendary. CD notes quote Alan Blythe as saying it represents

Callas "at the peak of her vocal powers," admiring that on

occasion "there

are a number of technical shortcomings." That is putting it mild!

At the time, Callas should have been at her best, but she produces

some incredibly ugly sounds,

not helped by a recording that originally had some distortion. Often

her pitch is suspect, and it is hard to imagine that Karajan, a stickler

for perfection, might not have said to her, "Maria, do you really want

to try that D flat at the end of Butterfly's entrance?" She did give

it a stab, and her wobble on that treacherous note is rather pathetic.

No

question that dramatically she is magnificent, but for me that cannot compensate

for vocal defects. The remainder of the cast is superb, as is Karajan's

approach to the music, and

Andrew Rose's remastering has worked wonders on this recording made well

over a half century ago. However, for a beautifully sung Butterfly, there

are dozens of superior recordings, particularly those featuring Mirella

Freni, de los Angeles, Caballé, and Tebaldi, to mention only a few

that offer vocal perfection.