This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

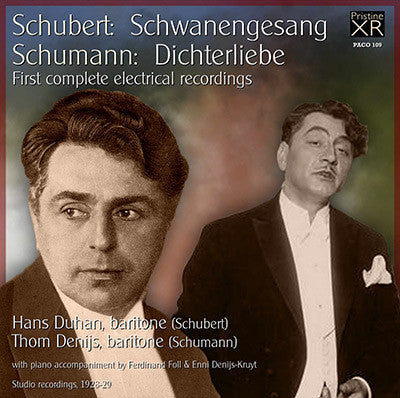

Rare first complete electrical recordings of Schwanengesang and Dichterliebe, new XR-remastered transfers

"The Duhan records of Schubert are not likely to be excelled" - "My personal choice is for Denijs [in Dichterliebe]" - The Gramophone

Both of these song cycle recordings were transferred from HMV 78s

kindly lent to me by Richard Morris of the Schubert Institute (UK), who

noted "I intend to mention the release in our journal, since the

recording has effectively been unavailable for 50 years, so I doubt that

any members have heard it." Well they're in for a treat - the Schubert

is exceptionally well recorded for its vintage, with the slight

exception of the very last side, which was prone to overload distortion.

The cycle was recorded over four sessions between October 1928 and

January 1929 and benefits from particularly clear vocal reproduction,

further enhanced in this XR remastering. Rather confusing was the

pitching of the cycle: the two sides cut in 1929 were pitched at A444,

whilst those recorded the previous year came in at around A452. I

elected to use the lower of the two pitches for the complete cycle, and

was also able to smooth out some variable pitch most noticable during

the piano solo sections. Although there is some overall variability in

tone from the various recordings (and disc sizes) the complete cycle is a

superb example of just how quickly and well the recording companies had

adjusted to life with microphones by 1928.

The Thom Denijs

Schumann cycle was recorded on a single day in January 1928 and at first

appears to come from a different era, largely thanks to the rather

clangy piano tone. But quickly one is drawn in to the different acoustic

(and forgets the slightly higher surface noise) and the voice. In a

1937 review of Gerhard Husch's Dichterliebe, The Gramophone's critic

noted the previous existence of this set, stating: "My personal choice

is for Denijs because I find his light baritone voice the more

attractive. Technically the new records are the better; the piano tone

in the earlier set is rather thin."

Andrew Rose

-

SCHUBERT Schwanengesang, D.957

Recorded 20 October 1928 (1, 3, 5, 7-10)

23 October 1928 (6, 11, 12

3 November 1928 (4, 14)

24 January 1929 (2, 13)

Issued as Czech HMV ER 292-95 & ES 460, 471 & 507

Matrices: BW1934-II; CW2155-I; BW1935-II; CW1965-II

BW1936-II; CW1949-II; BW1937-I;38-I;39-II; BW1947-1

BW1948-II; CW1950-II; CW2156-I; CW1964-II

(BW=10-inch 78s; CW=12-inch 78s)

Hans Duhan baritone

Ferdinand Foll piano

-

SCHUMANN Dichterliebe, Op. 49

Recorded 18 January 1928

HMV Studio B, Hayes, Middlesex

Issued as HMV D.2062-64

Matrices: Cc.12377-II; 12378-II; 13952-II

13953-II; 12381-I; 12388-IIThom Denijs baritone

Enni Denijs-Kruyt piano

Fanfare Review

Lieder enthusiasts will want to get this release, and for very good reasons.

What we get on this album are two firsts: the first complete recordings of Schwanengensang and Dichterliebe. Both were recorded in 1928, with the former’s sessions shading into the first part of the following year. Both were well received by critics at the time, though I can’t find any fans of vintage singing ecstatic over these performers as is the case with Elena Gerhardt, Karl Erb, and Charles Panzéra.

Hans Duhan (1890–1971) had the more notable career. He debuted as Amonasro in 1914 at the Vienna Court Opera, and appeared frequently as Count Almaviva, Scarpia, Don Fernando (Fidelio), Pasha Selim, and Frank (Die Fledermaus). He was the first Daniello in the premiere of Krenek’s jazz opera, Jonny spielt auf, and both the Music Master and Harlequin in the premiere of the revised version of Ariadne auf Naxos, in 1916. His Lieder recitals took a secondary place to his opera performances, but he was no tyro: He was the first singer to record all three of Schubert’s song cycles, Die schöne Mullerin, Winterreise, and Schwanengesang.

Duhan has the advantage in very close miking that reveals a bright, typically white Teutonic tone. Despite having recorded Schwanengesang over four sessions, there’s some evidence that the voice is a little large for the music—or at least that Duhan wasn’t in best voice in the first of those sessions, on October 20, 1928, which only resulted in five accepted selections. In “Frühlingssehnsucht,” the tone is slightly spread on “erfüllt,” and there’s some evidence of strain in “Wie habt ihr den pochenden Herzen gethan.” “Liebesbotschaft” has a few slurred notes (“Busen,” “Rosen”) and intonation issues at the conclusion of “mit kühlen der Fluth.” These last also crop up in “Abschied,” where there’s no sense of lightness whatever. He is in better form on all three other sessions, though turns and figurations are still occasionally smudged. The finesse and more agile qualities associated with a baritono lirico may have been beyond Duhan’s reach when he had become a celebrated baritono cantabile. (Not that all voices associated with heavier roles are precluded from lightening sufficiently. The Soviet lyric dramatic tenor Solomon Chromchenko was quite capable even late in his career of singing lyric tenor arias with great ease and lift.)

Duhan is not an “inner” Lied singer. The emphasis isn’t on interpretation of the words, but on voice. He is attentive to markings, but he treats each song in a relatively generalized way. He is at his best in the “Ständchen,” where his steady, burnished tone and very clear enunciation are strong assets. “In der Ferne” reveals him taking his dramatic cues from the music: “Wehe dem fliehenden Welt hinaus Ziehenden” may not have the word-by-word coloring one desires in this music, but the line overall has a firm directness and oppressive weight well suited to its meaning. And he manages a good reduction in the thread of tone in the opening line to “Ihr Bild,” reflecting the despondency of loss. If this isn’t a Schwanengesang to love, it’s certainly one to respect, and is welcome back into the active catalog.

By contrast, the career of Thom Denijs (1877–1935) was more modest, and devoted largely to Lieder rather than opera. After a few years in lyric baritone parts with the Amsterdamsch Lyrisch Toneel, he decided to focus on oratorio and song. He was best known at first for his fine performances in the Bach St. Matthew Passion under Mengelberg’s direction, and then spent much time in Berlin, touring as a Lieder singer, accompanied by his wife. (Pristine Audio lists Enni Denijs-Kroyt as the pianist in the song cycle. She was not given credit on the original records, though the chances of anybody else taking part are miniscule, given the couple’s lengthy professional partnership.)

Unlike Duhans, Denijs recorded all 16 songs of Schumann’s Dictherliebe on a single day: January 18, 1928. That would be accounted something of a feat by most record companies, even at the time. Unlike tape and post-tape methods employed generally since the 1950s, Denijs had to complete each selection in a single take, evaluate it with his producer or engineer, and redo it or move on to the next piece. If there’s a hint of strain occasionally at both ends of his vocal spectrum, that’s not surprising. Denijs was already 50, and he was giving his voice, body, and mind a very solid workout.

That fine critic and voice teacher, Herman Klein, noted the release this way. “A highly artistic rendering … and the singer—a most agreeable tenor with baritonal middle notes—has obvious intelligence in addition to a refined style, poetic feeling, and an unusual command of contrast.” Klein’s method of evaluating range is interesting, but it’s his point about contrast that zeros in on the most salient feature of these recordings. “Wenn ich in deine Augen seh” begins with a veiled, softly floating tone, but by “so wer’d ich ganz gesund,” the voice has gradually opened up to full throttle. He then reduces it quickly in the next line, with an especially magical ornamented descent on “mich lehn’ an deine Brust.” The recording process of the day wasn’t kind to the human voice at its extremes in dynamics, and I suspect the reason these records have poor presence is that his engineers moved Denijs to a moderate distance from the mike in order to prevent overloading. The piano suffers even more in this respect, with a boxy, thin, clangorous sound.

The performances in any case have a rapt, inner feeling. Denijs was an old hand by then at Lieder recitals, and he knew how to tell an expressive tale with his voice and treatment of words that would leave an audience spellbound. So it goes, elsewhere: Ich will meine Seele tauchen is taken down a full step, and even so, Denijs has trouble with the E on “hauchen,” but what a wealth of expression there is as he tells a story: the careful caress of the “l”s in “Ein Lied von der Liebsten mein,” the slight push on the opening digraph of “schauern,” the briefly rapt “wie der Kuss,” the sudden delicacy on “wunderbar süsser Stund.” A few of the liberties Denijs takes may seem a bit over the top today, but he was abstemious compared to some of his colleagues of the time. In any case, despite his obvious study of these works, he never sounds studied; his is an art that remains fresh.

Producer Andrew Rose notes that he’s dealt with some variable pitch issues, as well as cleaned up surfaces and lessened distortion. This kind of non-invasive approach works wonders on these selections. Duhan’s tone is beautifully caught, and the full dynamic range and interpretative ability of Denijs likewise are caught very well. Lieder enthusiasts will want to get this release, and for very good reasons.

Barry Brenesal

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:4 (Mar/Apr 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.