This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

"The most uplifting, superbly executed reading of Act 3 in the history of recording" - Gramophone

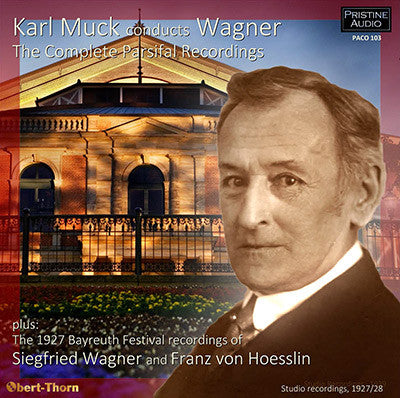

Karl Muck's 1927-8 Parsifal recordings - plus 1927 Bayreuth recordings by Siegfried Wagner and von Hoesslin

For the first three decades of the Twentieth Century, Karl Muck (1859 - 1940) was identified with Wagner’s Parsifal to a degree later rivaled only by Hans Knappertsbusch. Muck inherited the Bayreuth presentations of the opera from its première conductor, Hermann Levi, in 1901, and proceeded to lead it in all fourteen festivals held there between then and 1930. His interpretation was considered definitive by many critics, both contemporary (American critic Herbert Peyser called it “the only and ultimate Parsifal; the Parsifal in which every phrase was charged with infinities; the Parsifal which was neither of this age nor that age, but of all time”) and modern (Alan Blyth cited Muck’s 1928 Berlin set in Gramophone as “the most uplifting, superbly executed reading of Act 3 [...] in the history of recording”).

Although a complete recording of Parsifal during the 78 rpm era was unfeasible due to the number of sides required, Muck managed to set down more than a third of the work over three groups of sessions spanning fourteen months. The first took place at Bayreuth during the summer of 1927, where Columbia also recorded Siegfried Wagner, the composer’s son, in further excerpts from Parsifal, and Franz von Hoesslin in scenes from the Ring.

For

all the advantages of recording in the Festspielhaus, the engineers

were mostly unsuccessful in capturing the hall’s unique acoustics. The

orchestra appears to have been moved out of its covered pit and onto the

stage, while the vocal soloists are positioned in extreme proximity to

the microphone. Only in some of the unaccompanied choral passages and

the occasional reverberation at the end of a side can one get a true

sense of the venue’s warmth. (One advantage of the location, however,

was the chance to preserve the sound of the original Bayreuth bells (right). Made for Parsifal’s

1882 première, they were tuned to a noticeably lower pitch than the

orchestra was using by the 1920s. The bells were later melted down for

the German war effort, and this is their only recording.)

For

all the advantages of recording in the Festspielhaus, the engineers

were mostly unsuccessful in capturing the hall’s unique acoustics. The

orchestra appears to have been moved out of its covered pit and onto the

stage, while the vocal soloists are positioned in extreme proximity to

the microphone. Only in some of the unaccompanied choral passages and

the occasional reverberation at the end of a side can one get a true

sense of the venue’s warmth. (One advantage of the location, however,

was the chance to preserve the sound of the original Bayreuth bells (right). Made for Parsifal’s

1882 première, they were tuned to a noticeably lower pitch than the

orchestra was using by the 1920s. The bells were later melted down for

the German war effort, and this is their only recording.)

In December of the same year, the action shifted to Berlin, where HMV set down several sides of Muck conducting Wagner orchestral works, including the Prelude to Act 1 of Parsifal, in the Singakademie. Six months later, most of Act 3 was recorded there; (about 16 minutes of music at the beginning of the act were cut). Here, the engineers achieved better results, although most of Amfortas’s scene was only issued in a sonically compromised dubbing.

In order for Act 3 to be presented uninterrupted on the CD edition of this release, the Bayreuth recordings of von Hoesslin and Siegfried Wagner are presented before Muck’s excerpts, except for the Kipnis/Wolff “Good Friday Spell”, which appears at the end. Multiple copies of the finest pressing vintages were drawn upon for the present transfers: American Columbia “Viva-Tonal” and pre-war “Microphone” label copies for the Bayreuth recordings, and Victor “Z” and “Gold” label pressings for the Berlin sides. Some remaining flaws are inherent in the original recordings.

Mark Obert-Thorn

CD 1 (77:23)

WAGNER: Das Rheingold Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla (6:45)

Woglinde: Maria Nezádal (soprano); Wellgunde: Minnie Ruske-Leopold (soprano); Flosshilde: Charlotte Müller (alto)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3002-1 & 3003-1 (Columbia L 2016)

WAGNER: Die Walküre Ride of the Valkyries (Act 3) (7:07)

Gerhilde:

Ellen Overgaard (soprano); Ortlinde: Henriette Gottlieb (soprano);

Waltraute: Erika Plettner (alto); Schwertleite: Maria Peschken

(mezzo-soprano); Helmwige: Ingeborg Holmgren (soprano); Siegrune: Minnie

Ruske-Leopold (soprano); Grimgerde: Charlotte Müller (alto); Rossweise:

Charlotte Rückforth (alto)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3004-1 & 3005-2 (Columbia L 2017)

WAGNER: Siegfried

Forest Murmurs (Act 2)* (3:05)

Prelude to Act 3 (4:05)

Fire Music (Act 3) (4:02)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3009-2*, 3000-3 & 3001-1 (Columbia L 2014* & L 2015)

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra · Franz von Hoesslin

WAGNER: Parsifal Prelude to Act 3 (5:54)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3023-2 & 3024-1 (Columbia L 2012)

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra · Siegfried Wagner

WAGNER: Parsifal

Act 1 Prelude (15:54)

Recorded 11 December 1927 in the Singakademie, Berlin

Matrix nos.: CWR 1421-2, 1422-2, 1423-1A & 1424-1A (HMV D 1400/1)

Berlin State Opera Orchestra · Karl Muck

Transformation Music (7:17)

Grail Scene:

Zum lezten Liebesmahle (5:40)

Durch Mitleid wissend, der reine Tor (8:06)

Wein und Brot des letzten Mahles (4:33)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3010-1, 3011-2, 3012-1, 3013-2, 3014-2, 3015-1, 3016-1 & 3017-1 (Columbia L 2007/10)

Act 2 Komm’! Komm’! Holder Knabe! (Flower Maidens Scene) (4:55)

Flower Maidens:

Ingeborg Holmgren (soprano); Anny Helm (soprano); Minnie Ruske-Leopold

(soprano); Hilde Sinnek (soprano); Maria Nezádal (soprano); Charlotte

Müller (alto)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3018-2 & 3019-1 (Columbia L 2011)

Bayreuth Festival Chorus (Chorusmaster: Hugo Rüdel)

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra · Karl Muck

CD 2 (74:20)

WAGNER: Parsifal

Act 3

Prelude (6:38)

Heil mir, dass ich dich wieder finde! (4:24)

O Gnade! Höchstes Heil! (13:59)

So ward es uns verhiessen (Good Friday Spell) (12:43)

Mittag: Die Stund’ ist da (Transformation Music) (5:17)

Geleiten wir im bergenden Schrein (3:39)

Ja, Wehe! Wehe! (7:07)

Nur eine Waffe taugt (9:59)

Recorded 10, 11, 13 & 14 October 1928 in the Singakademie, Berlin

Matrix

nos.: CLR 4609-2, 4610-2, 4598-2, 4599-2, 4600-2, 4601-1, 4602-2,

4603-1, 4604-2, 4611-1, 4612-1, 4613-1, 4614-1T1, 4615-1, 4616-1 &

4617-1 (HMV D 1537/44)

Parsifal : Gotthelf Pistor (tenor); Gurnemanz: Ludwig Hofmann (bass); Amfortas: Cornelius Bronsgeest (baritone)

Berlin State Opera Chorus (Chorusmaster: Hugo Rüdel)

Berlin State Opera Orchestra · Karl Muck

WAGNER: Parsifal - Act 3 So ward es uns verhiessen (Good Friday Spell) (10:33)

Recorded August, 1927 in the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth

Matrix nos.: WAX 3020-1, 3021-2 & 3022-1 (Columbia L 2013/4)

Gurenemanz: Alexander Kipnis (bass); Parsifal: Fritz Wolff (tenor)

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra · Siegfried Wagner

Fanfare Review

Muck’s mastery over technique and meaning creates a transcendent experience.

My late, dear friend, the critic Marion Lignana Rosenberg, had one of the peak experiences of the last year of her life reviewing Parsifal at the Met. Marion’s specialty was Italian opera, and I think she might have agreed with my high school music teacher that “Wagner is an Italian composer.” Wagner is a master at drawing out the cantilena of his themes, very much in the manner of bel canto. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Parsifal. I think Marion also was drawn, in her scholar’s way, to the notion of opera as ritual, which Parsifal epitomizes. In Karl Muck’s Parsifal recordings, we have both the thematic substance and the ritualistic mystery of the opera raised to their highest level. Thomas Mann described Wagner’s music as “forces struggling out of dark confusion to find deliverance in beauty.” So much of this description pertains to Muck’s Parsifal. Always we find the struggle with the confusion and sinfulness of the world, leading not just to beauty but to spiritual redemption. In every note of Muck’s Parsifal there is certainty as to the path of this journey. Adrian Boult wrote that ideally one should witness just one act of a Wagner opera each night; that’s all one can take. Never has Boult’s dictum struck me more forcibly than with Muck’s Parsifal. It is an experience of the most rarefied musical and dramatic intelligence.

Muck sees the Prelude to act I (recorded in Berlin) not as a mere veil of mystery enshrouding the opera, but as actual prophecy. At nearly 16 minutes long, his performance is over three minutes slower than Claudio Abbado’s. Nevertheless, there is a constant revelation of emotion, as if Muck were consulting a Sibyl. His gradations in tempo and dynamics are masterly, yet with an ebb and flow that never lets them become mechanical. The shifting colors and harmonies in the orchestration sound brand new, contributing to the feeling of the miraculous taking place before our eyes. Muck summons the deepest human passions like a wizard. The remainder of the act, recorded in Bayreuth, begins with the Transformation Music, over two minutes slower than Boult’s. Rarely has it so exhibited the aspiration for the divine as found in a place of sanctuary, the sacred Hall of the Grail. Muck shows how if prefigures the procession and ritual of the knights, enhanced by the otherworldly sound of the original bells cast for the opera. Most of the Grail Scene follows, minus the vocal soloists. The first chorus of the knights is imbued with divine fervor. Muck elicits the overtones of German Renaissance polyphony when the pages sing of divine communion. He gets a deep tone out of the cellos to preface the consecration of the bread and wine. The consecration itself is marked by rapt sounds from the orchestra. The transfiguration of a martial tread into the final exhortation to faith and love is beautifully handled. Muck also recorded a section of act II’s Flower Maidens Scene, minus a Parsifal. The maidens sound a bit matronly to have been born in the spring, but they engage in some Bavarian flirtiness.

Muck, in Berlin, recorded most of act III. His soloists are distinguished. Gotthelf Pistor, as Parsifal, produces a full but light tone, with an appealing youthfulness and simple nobility that is most affecting. Ludwig Hoffman has a rock-solid technique over a broad range; his Gurnemanz is both strong and compassionate. Cornelius Bronsgeest may not have quite the vocal allure of his colleagues, but he conveys Amfortas’s suffering most effectively. Muck’s slow Prelude begins with stark, Sibelius-like tones, psychologically establishing Parsifal’s internal sense of grief. After the music reaches a crisis, Muck suggests Parsifal’s feeling of resolution, nearly subdued by his sorrow. In the action, there is a sunburst of immense majesty from the orchestra when Gurnemanz declares Parsifal king. Muck presents the whole Good Friday Spell as a tremendous arc of beauty and passion. The orchestra’s tone colors are reminiscent of the Siegfried Idyll as Parsifal looks toward the meadow. The procession of the knights, in Muck’s reading, recalls Thomas Mann’s words about the “pessimistic heaviness and measured yearning” in Wagner. The opera’s final pages for chorus and orchestra go at a stately tempo which combines nobilimente and tenderness. Muck reminds us that these are Wagner’s last musical thoughts; at the ending there is a sense of release from the world of the stage and perhaps from life itself.

Siegfried Wagner’s Bayreuth excerpts from act III make an instructive contrast with Muck. The Prelude is a little quicker with a far greater emphasis on lyric beauty, yet lacks the psychological depth and drama of Muck’s interpretation. The composer’s son is four-square in the Good Friday Spell, handcuffing the phrasing of an otherwise able Parsifal, Fritz Wolff. The redeeming feature of this excerpt is the Gurnemanz of Alexander Kipnis, an absolutely amazing performance technically and stylistically. The Bayreuth Ring excerpts, marred by cuts and an under-rehearsed orchestra, are valuable for documenting the art of Franz von Hoesslin, who was active at Bayreuth well into the Nazi regime, despite having a Jewish wife. He chooses sensible tempos and has a good dramatic sense. The Bayreuth recordings of all three conductors were made in August 1927. Mark Obert-Thorn has revealed much detail in them in his remastering, although they remain rather unatmospheric. Muck’s Berlin recordings, from 1927–28, are fuller and warmer in tone, more than realistic enough to convey the achievement of his interpretation. Not everyone was a fan of Muck. Toscanini, in a well-calibrated Wagnerian insult, called him “the Beckmesser of conductors.” But his technical skills were beyond reproach. Sergei Rachmaninoff said that, as a pianist, the only two conductors he couldn’t “lose” in performance were Muck and Eugene Ormandy. In Parsifal, Muck’s mastery over technique and meaning creates a transcendent experience. I doubt there is anyone like him today.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:1 (Sept/Oct 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.