This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

The Oprichnik: Tchaikovsky's elusive third opera in its first recording

A roaring success when first performed - one of only four complete recordings

This was the first of only a very small number of recordings of Tchaikovsky's third opera, one of his least-known, to have been made. Even today, The Oprichnik remains an elusive work, and despite a small number of relatively minor cuts (mainly in the fourth act) it's largely intact and can thus be seen as a definitive interpretation by performers and, in particular, Aleksander Orlov, a conductor seeped in the history of Russian opera.

Technically it's remarkably successful for its day. The Russians, like their western counterparts, were quickly adapting the magentic tape technology they found at the end of the war in Germany for their own uses, at a time when full-length operas of this magnitude (especially forgotten ones) were few and far between in the recorded canon and the standard issue would have been (at a guess) some 40 or more 78rpm sides.

The microphones used, particularly for the soloists, appear suspect at times, with a tendency to peak distortion and a somewhat thin sound for the male voices against the fuller orchestra and choir. This is less apparent later in the opera, and overall it's a very commendable production. XR remastering and a very light touch of convolution reverberation has worked wonders with this occasionally difficult raw material.

Andrew Rose

TCHAIKOVSKY The Oprichnik

Libretto: Tchaikovsky, from the play "The Oprichniks" (Опричники) (1842) by Ivan Lazhechnikov

Setting: Ivan the Terrible's court during the oprichnina times (1565–1573)

Recorded Moscow, 1948

Transfer from Melodiya 33.D.09821-28

CAST

Prince Zhemchuzhny - Alexei Korolyov

Natalia - Natalya Rozhdestvenskaya

Molchan Mitkov - Vsevolod Tyutyunnik

Boyarina Morozova - Lyudmila Ivanovna Legostayeva

Andrei Morozov - Boris Tarkhov

Basmanov - Zara Dolukhanova

Prince Vyazminsky - Konstantin Polyaev

Zakharyevna - Antonina Kleschtschova

Moscow Radio Choir and Orchestra

conductor - Aleksandr Ivanovich Orlov

An oprichnik (Russian: опри́чник, man aside; plural Oprichniki) was a member of an organization established by Tsar Ivan the Terrible to govern the division of Russia known as the Oprichnina (1565-1572). It is thought by some scholars that it was Ivan's second wife, the Circassian Maria Temryukovna who first gave the Tsar the idea of forming the organization. This theory comes from a German oprichnik, Heinrich von Staden. Her brother also became a leading oprichnik.

Their oath of allegiance was:

I swear to be true to the Lord, Grand Prince, and his realm, to the young Grand Princes, and to the Grand Princess, and not to maintain silence about any evil that I may know or have heard or may hear which is being contemplated against the Tsar, his realms, the young princes or the Tsaritsa. I swear also not to eat or drink with the zemschina, and not to have anything in common with them. On this I kiss the cross.

Oprichniki are regarded as the forerunners of Russian and Soviet secret police.

Synopsis

ACT I

Moscow. Boyar Zhemchuzhny's garden.

Zhemchuzhny wants to marry his daughter to the old Boyar Mitkov but

Natalia loves Andrey Morozov to whom she has been betrothed since

childhood days. Slandered by Zhemchuzhny, Andrey's father was executed

at the orders of Ivan the Terrible and Andrey was deprived of his

inheritance. To take vengeance against Zhemchuzhny and help Natalia

escape from home, Andrey, on the advice of his friend, the Oprichnik

Fyodor Basmanov, decides to join the Oprichnina.

ACT II

Scene 1. A cottage to which Andrey and his

mother moved after their ruin. The proud Boyar loves her son as much as

she hates the Oprichnina. Andrey comes home, bringing some money which

Basmanov has given him. His mother refuses to accept help from an

Oprichnik. Afraid to distress her Andrey tells her nothing of his

intention to join the Oprichnina.

Scene 2. The Alexandrov Sloboda where the tsar has his abode. Andrei Morozov is being initiated into the Oprichnina. He pronounces the formidable vow of loyalty, renouncing his friends and family, his beloved mother. Among those present is the tsar's favourite, cruel Prince Vyazemsky, who has always hated the Morozov family and who now intends to take advantage of Andrey's hesitance to bring about his doom.

ACT III

The city square. Natalia who has fled her

father's house came to beg Andrey's mother for asylum and protection.

But the Boyar refuses. Natalia's father overtakes her and orders his

servants to tie her hand and foot. A group of Oprichniks, Morozov and

Basmanov among them, come up and free the girl. Andrey's mother now

understands that her son has joined the Oprichnina. She curses him.

Andrey decides to ask the tsar's permission to leave the Oprichnina.

ACT IV

The Alexandrov Sloboda. The Oprichniks are

celebrating Andrey's wedding with Natalia. Natalia is filled with alarm.

The tsar has allowed Andrey to leave the Oprichnina, but the young man

is bound by his oath until midnight. Before the expiration of the term,

however, Prince Vyazemsky arrives stating that the tsar bids Natalia to

come to him. In vain does Basmanov persuade Andrey that this is a test

of loyalty to the tsar. Andrey refuses to let Natalia go and thus

violates his oath.

The guests disperse. Triumphant, Vyazemsky brings in Andrey's mother and asks her to look out of the window. Outside a scaffold is being set up. The mother sees her beloved son, whom she has cursed, being led to his death. She drops to the floor in a deadly swoon.

A gloomy, solemn chorus of the Oprichniks sings glory to the terrible tsar.

Synopsis from Melodiya LP issue

Fanfare Reviews

Urgently, even passionately, recommended

Back in 37:1 I reviewed a c. 1980 stereo recording of Tchaikovsky’s The Oprichnik conducted by Gennady Provatorov. In recommending that at the time as a first choice over the only two other recordings ever made, I commented on this premiere recording from 1948 as follows: “The conducting is first-rate; the vocal cast is solid but overall inferior to the one on this recording; the recorded sound is quite good for its provenance; and a couple of minor cuts (about 10–15 minutes of music) are made to the score. Regrettably, it is one of the few historical Soviet-era opera recordings that has not yet made its way onto CD, though it should; an MP3 download version is now available on Amazon.” As fortune would have it, a short time later Andrew Rose of Pristine Audio announced that he had received a collection of historic Russian opera recordings and would be refurbishing and reissuing those on his own label. I wrote to him post-haste to ask if the 1948 Oprichniki might be among them. Not only did he indeed have it, but in response to my request he moved it to the front of the production line, and here you have the splendid result.

“Splendid” is indeed the right word. Working from an original Melodiya LP set rather than the second-generation Ultraphone knock-off once available in the USA, Rose has lifted a suffocating sonic shroud and brought out far more sound than I ever would have imagined possible. Of course, nothing will ever turn a 1948-vintage Melodiya recording into something comparable to the best European and American recordings of the same era: There is still the harsh edge to the treble range, particularly in the violins, and some blaring and shattering from the brass. But even so, the sound is now far more natural, with particular benefit to the voices. A particular oddity I have encountered (and for which I wish I had a good explanation) is that a poor LP mastering of an opera will selectively make some but not all of the singers’ voices appear to have uneven vibratos or other flaws. That was the case in this set, with Rozhdestvenskaya, Legostayeva, and Tyutyunnik seeming to have incipient wobbles and Polyaev, Korolyov, and Tyutyunnik sounding rather harsh and desiccated. Having no other basis at the time than the Ultraphone set on which to judge them, I assumed that their voices were indeed unevenly produced and accordingly endorsed the Provatorov recording as the superior alternative. But with Rose’s XR sonic wizardry at work, those defects have vanished; except for Konstantin Polyaev, whose production remains slightly diffuse, all the singers are now revealed to have firm, steady voices (though both Rozhdestvenskaya and Legostayeva have a few slightly strained top notes), and the baritones and basses, while not in the league of Pavel Lisitsian or Mark Reizen for richness and beauty, have far more body and amplitude than one might have thought.

Even more to the point, all the singers also have a vibrancy of vocal character that has become smoothed out to a more generic sound in singers of subsequent generations. While perhaps not as technically polished at certain points, the singing is consequently more impassioned and interesting. Thus, while Natalia Rozhdestvenskaya (the mother of famed conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky) as Natalie has a more metallic and less beautiful voice than does Tamara Milashkina under Provatorov, she turns that to her advantage by using it to present a character who is more apprehensive and less naïve in nature and thus more of an active than passive participant in the action. Lyudmilla Legostayeva likewise has more body and bloom than does the otherwise estimable Larissa Nikitina for Provatorov, and the two bassos bring out more of a comic dimension to their brief parts in the opening scene. But perhaps the most striking characterizations are those of the legendary Zara Dolukhanova as Basmanov and the little-known but superb Boris Tarkhov as Andrei, the latter in particular wielding a ringing, thrilling, dramatic tenor of a sort that has become all too rare nowadays (though Lev Kuznetsov is likewise excellent, and Raisa Kotova as Basmanov quite fine as well, under Provatorov). With the exceptions of the roles of Natalie and Prince Vyazminsky, where the singers in each set have countervailing virtues and flaws that cancel one another out and lead to a draw, I would now reverse my previous judgment and give a slight but clear edge to the singers in this set for every other role. The choral work also is excellent. Aleksandr Orlov’s conducting reminds me of Yevgeny Svetlanov—unsubtle and sometimes a bit raw, but full throttle on the dramatic tension and emotional commitment such a score needs in order to have its proper effect. In sum, this release is a major and long overdue landmark in the CD discography of Russian opera.

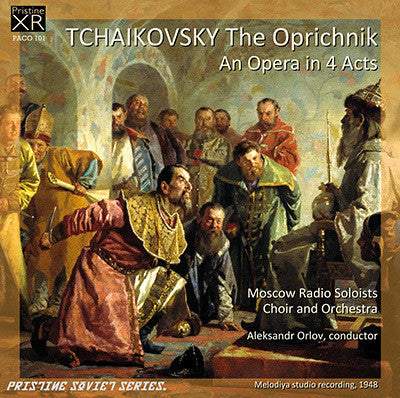

Because the Provatorov recording is excellent in its own right, has modern stereo sound, and does not have the minor cuts in acts II and III that this recording has, I can’t say that one now should unconditionally put it aside and make this version a first choice for this opera. I can and definitely will say that this release is the best sung version overall, and a must-have acquisition for any devotee of Tchaikovsky and Russian opera. I also wish to compliment Rose for a singularly fine choice of cover art for this release, an excellent reproduction of a 19th-century painting, “The Oprichniki,” by Nikolai Vasilyevich Nevrev (1830–1904). It brings back fond memories of the days when Angel/Melodiya LPs often featured reproductions of 19th-century paintings by Russian artists on their jacket fronts. Both the breaks between discs and the track points are sensibly chosen and superior to those on the Aquarius release of the Provatorov recording. In each of the past two years, a Pristine Audio release has just missed making my annual Want List. The third time is now almost certainly the charm; barring something else truly extraordinary appearing at the last minute, this set has a sure lock on one of the five slots for this year. Urgently, even passionately, recommended.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:6 (July/Aug 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.

Tchaikovsky frequently wrote large works with intense enthusiasm, only to react with revulsion upon their completion. That was the case with his opera The Oprichnik in 1874, following its tumultuous success. He expressed disgust with the violence of its plot, and his music’s manipulation of his audience. Later he would change his views and write another, still more violent opera, Pique Dame, whose music manipulated audiences with great success. Expressive extremes that manipulate audiences are, after all, something his music does well, whether in his operas, symphonies, or chamber music. (The only opera of his that avoids all the violence and emotive extremes, Iolanta, was his last and arguably his worst.) And, in The Oprichnik, Tchaikovsky does it very effectively indeed.

A tale of love, murder, loyalty, and revenge, with a conclusion that could have been lifted from Il trovatore, The Oprichnik is a numbers opera with a pronounced Russian folk cast to its themes and harmonic progressions. Shock-horror it is in its fourth act, but there’s a fine, light touch at many points in its first act, and a variety of interesting personalities pursuing their own agendas along the way. Tchaikovsky writes not only arias and dances, but several extended, complex scenes for individual characters, with a musical focus no less successful than in Yevgeny Onegin, premiered in 1879. By my very personal reckoning, The Oprichnik stands in a tie for first place among the composer’s operas, alongside The Enchantress. It’s just ahead of two others that are tied for second: the uneven but frequently insightful Onegin and The Maid of Orleans, of which the first two acts contain some of the finest operatic music Tchaikovsky ever wrote.

Sadly, The Oprichnik has received very few recordings over the years. This slightly cut one from 1948 has singing that ranges from good to spectacular. At the top end is a youthful Zara Dolukhanova in the trouser role of Basmanov. She dispatches it with a breezy, characterful zest that contrasts wonderfully with another part she recorded that same year, the fiercely vigilant Kascheyevna in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Kashchei the Deathless. Her even production is missing from Natalia Rozhdestvenskaya, and the latter has problems with singing full throttle too much. There’s more emotional range to Natalia than is caught here, though Rozhdestvenskaya has all the passion one could wish for. Lyudmilla Legostayeva sounds a bit thin and vinegary in her lower register, but finds the resonance to “take stage” in the more climactic moments of her act II aria.

Among the men, I’ve never cared for Konstantin Polyaev, one of those “To emote, I have to ignore the written line” singers, but his role is largely insignificant. By contrast, it’s great to hear Alexei Korolyov with a firm, resonant voice, 14 years before his finely characterized but vocally aged Tsar Dodon in Melodiya’s The Golden Cockerel. Boris Tarkhov was in that Golden Cockerel too, where his easy top served him well as The Astrologer. Here, his hard, white tone is the only significant drawback in a well-modulated performance, with some good metal as sporadically required. He was one of many excellent Soviet tenors to jostle for business over the next decade, including Kozlovsky, Lemeshev, Ivanovsky, Kromchenko, Nelepp, Makhov, Vinogradov, Orfenov, Khanaev, Maslennikov, Alexandrovitch, and Ognovoi. It’s no wonder many ended up with few major roles to their credit in complete opera recordings.

Alexandr Orlov, who had been conducting since 1902, died later in the year this Oprichnik was made. Each of his complete opera recordings (Onegin, Lakmé, La traviata, Oprichnik) demonstrates that he was a real veteran in the opera pit, adept at seconding his singers, if not as insightful as Golovanov.

Andrew Rose, who restored and produced this rerelease, praises its sound—rightly, in my opinion—as “remarkably successful for its day.” One might add, it was remarkably successful considering how erratic Melodiya operatic and orchestral recordings could be, then and for the next 20 years. At times they seem to have been made in caverns, or under water, or with miking so distant it might as well have been phoned in. Rose notes a thinness to male voices and some peak distortion early on, and gave it just a bit of reverberation to counteract the dry overall studio sound that was one of the few constants where Melodiya engineering was concerned for so very long. The result is clean, forward, and a little better than my 1970s LP pressing of this recording.

This Oprichnik is definitely worth the purchase. The performances are nothing if not involved, and there are good things to say about all the singers, especially Dolukhanova and Tarkhov. Rose is typically fastidious. Pristine Audio also supplies the vocal score as a download. It can chalk up another success with this release.

Barry Brenesal

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:6 (July/Aug 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.