This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Full Cast Listing

- Historic Gramophone Review

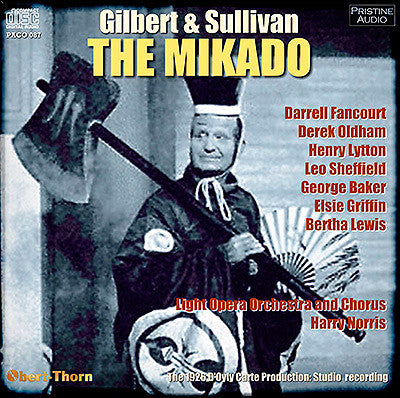

The 1926 D'Oyly Carte production of The Mikado - Superb new Obert-Thorn transfer

"the whole performance is extraordinarily good and sparkling" - The Gramophone, 1927

"it is doubtful that any better cast than this was assembled in the twentieth century" - The G&S Discography

The 1926 D’Oyly Carte production of The Mikado boasted several “firsts”. It was the first to use new costumes and scenery since the original production of 1885, and the first to broadcast a portion of the opening night performance on the radio, live from the theater. It would also become not merely the first Gilbert and Sullivan work, but the first opera of any kind to be recorded complete using the new electrical process.

As might be expected with such an early effort, the recording quality is variable. Some portions have much clarity and presence, while other sides sound dim and muffled. There are balance problems between singers and orchestra, and sometimes between one singer and another. The sides dating from the December 6th session are particularly problematic – bass-deficient, shrill and distorted.

Nevertheless, the set is significant in that it preserves the performances of several unforgettable Savoyards. As the Gilbert and Sullivan Discography website puts it, this was “the height of the so-called ‘golden age’ of G&S singing, and it is doubtful that any better cast than this was assembled in the twentieth century. Lytton, Lewis, Fancourt, Oldham and Griffin are all justifiably rated as G&S legends.” Chief among the attractions here is the Ko-Ko of Sir Henry A. Lytton, heir to the “patter” roles originated by George Grossmith and continued by Walter Passmore, who would himself turn them over to Martyn Green in the 1930s. (The recording also, unfortunately, preserves a racial slur in Ko-Ko’s “little list” and the Mikado’s litany of punishments, one which was not removed from the performing editions until 1948.)

The transfer has been made from the best portions of three late-Orthophonic U.S. Victor pressings, the quietest form of issue I have heard for this basically rather noisy set. Save for excerpts, it has never received an “official” LP or CD reissue.

Mark Obert-Thorn

|

ACT ONE |

ACT TWO |

GILBERT AND SULLIVAN The Mikado

THE CAST

The Mikado of Japan: Darrell Fancourt

Nanki-Poo, his son (disguised): Derek Oldham

Ko-Ko, Lord High Executioner: Sir Henry A. Lytton

Pooh-Bah, Lord High Everything Else: Leo Sheffield

Pish-Tush, a Noble Lord: George Baker

Go-To, a Noble Lord: T. Penry Hughes

Yum-Yum, ward of Ko-Ko: Elsie Griffin

Pitti-Sing, schoolfriend (shared role): Aileen Davies*, Doris Hemingway**, Beatrice Elburn***

Peep-Bo, another schoolfriend: Beatrice Elburn

Katisha, a Lady of the Mikado’s court: Bertha Lewis

Light Opera Orchestra and Chorus

Harry Norris, conductor

(Pitti-Sing: *CD 1, Tracks 12, 16 & 17; CD 2, Tracks 7, 8, 9 & 13 - **CD 1, Track 11; CD 2, Track 3 - ***CD 2, Track 1)

Recorded in Small Queen’s Hall, London

Originally issued in HMV Album 38

Special thanks to Nathan Brown and Charles Niss for providing source material

The Mikado. Produced at the Savoy, March 14th, 1885.

In the old set (H.M.V., D.2-D.12 [rec. 1917])

the overture, especially the second half, was the pick of the whole

bunch, and Radford the pick of the artists. The tenor and soprano both

seem a little flat in their top notes, and the tenor further lacks the

sense of the opera which Oldham has. The second verse of Pish-Tush's

song Our great Mikado was cut, and I am glad to find it restored in the new set, and there were a few minor ones as well.

The new set has every advantage, not only improved recording, but also

the actual singers that we know in the theatre, available to no other

recording company. There are, however, some small faults. Oldham in A Wandering Minstrel I

is excellent and sympathetic, but uses falsetto at the end which should

be unnecessary for so good a singer. Sheffield and Fancourt are neither

of them vocally so good as Radford, but are first-rate nevertheless.

Fancourt in the Mikado's song "fair gives one the creeps," even though

he cannot make such an excruciating "gulch" as Leicester Tunks used to

do. Ko-ko is bound to lose most through being invisible, and Lytton

seems to feel this. At any rate, he is inclined to be mechanical,

delightful though he always is, even at a discount. As for the women,

whereas Violet Essex sings The Sun whose rays with dramatic

effect but flat, Elsie Griffin sings it blamelessly but with-no dramatic

effect at all. Bertha Lewis is first-rate, as one feels sure before

coming to her. Three little maids is capitally sung and the Madrigal

is heavenly, especially the piano, but the whole performance is

extraordinarily good and sparkling, one good thing after another, in

fact - with one serious blemish, the overbearing orchestra already

referred to. There are certain variations from the original score, but

in accordance with invariable stage practice; for instance, So please you, Sir as

originally written. included Pish-Tush as well as Pooh-Bah and the

three Little Maids. In the finale a few bits of accompaniment are cut

out to save time, but every word of the libretto is there apart from the

dialogue.

Excerpt from "Savoy Opera Records" by N. M. Cameron, The Gramophone June 1927

Fanfare Review

To this day, the 1926 Mikado remains one of the most exciting, and best sung, versions of the opera on record

It was both a financially and artistically sensible decision to record The Mikado in 1926. The last released version dated as far back as 1917. The new recording would feature the latest development in audio, utilizing a microphone to replace the old acoustic horn, opening up a world of formerly unavailable, higher frequencies. (It would also cause a few more thoughtful critics, such as Sullivan’s friend, Herman Klein, to bemoan the exaggerated bass response of the new technology in recordings of close proximity, but the tradeoff was more than worth it.) It was timed to coincide with a new production of the opera, as well, the first to offer fresh sets and designs since the original in 1885. The D’Oyly Carte Opera Company went further, shrewdly joining with Gaumont to issue a silent, hand-colored, four-minute promotional film showing off the cast acting in front of the sets. (It still exists and can be found online, though with little surviving of the original coloration.) The sense of occasion even drew a youthful BBC to broadcast live excerpts on September 20 from a performance at the Princes Theatre.

It was a first for The Mikado in another sense as well. The 1917 HMV set was produced without the involvement of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, who only went as far as to lease out the rights to the work. None of the artists were famed professionally for performing G& S; indeed, nearly all the roles were split between two and even three (in the cases of Pish-Tush and Pitti-Sing) house performers of the recording company. By contrast, nearly all the singers in this 1926 Mikado recording appeared in the new production. A person at the time who purchased HMV 38, as it was listed in the day’s catalog, would presumably have been delighted at the performers’ theatrical involvement, as well as the richness and immediacy of the voices. (If you doubt the latter, just listen for an hour or so to some acoustic recordings from the early 1920s, and then hear this.) To this day, the 1926 Mikado remains one of the most exciting, and best sung, versions of the opera on record.

On to the singers. Derek Oldham is one of the best G& S tenors on record. His tone possesses a lot of head resonance; and buoyed along by good control of dynamics and shading, creates the musical embodiment of those G& S roles noted for poetic sentiment. The outer sections of his “A wand’ring minstrel I” have only been equaled and never bettered, though he has solid higher notes for the “And if you call for a song of the sea” section too.

Bertha Lewis is regarded by many as the finest principal contralto ever engaged by the D’Oyly Carte. She has an opulent, perfectly focused tone, rock-solid breath support, strong interpretative powers, and the personality to bring it all across. Oldham remarked in an interview once that she used to enter the stage muttering under her breath, “There’s no room, there’s no room!” and take instant command of everything in sight. Her Katisha is noteworthy for the beauty of voice and tragic depth she brings to “The hour of gladness” in the act I finale. It is a fitting monument to an artist who died at the age of 43 in 1931, five days after sustaining fatal injuries in an automobile accident.

As it happens, Henry Lytton was driving the car that had Lewis as a passenger at the time. He was unfortunately long past his vocal prime when he recorded this Ko-Ko; in fact, he first joined the D’Oyly Carte chorus as far back as 1884. Lytton’s talents brought him quickly to prominence, and he displays a fine bel canto line in early G& T recordings made in the first decade of the century, such as “Time was when love and I,” from The Sorcerer. By the 1920s, however, the notes often fell by the wayside. He gets the words and meaning across here, but the tone itself is always vinegary and sometimes unsteady.

Leo Sheffield is somewhat overparted as well. Too often the thread of the voice breaks, the intonation slips, or the muffled low notes seem to come from somewhere down in the collar, despite his clear grasp of Pooh-Bah’s character. In Sheffield’s defense, like Lytton, he was accounted a consummate stage performer, and we are all too used nowadays to basses taking the role, when in fact it was originally assigned to a baritone. Sheffield is also said to have suffered from great fright in front of the microphone. He is at his best in the trio, “I am so proud.”

But Elsie Griffin is always a joy to hear. She fortunately recorded several soprano roles in G&S: Rose Maybud (1924), Mabel (1929), Kate (1929), and Josephine (1930). Yum-Yum’s “The sun whose rays” isn’t well caught by the microphone—her voice veers between too loud and too distant, with too little of the color that’s caught better in The Pirates of Penzance—but it is very finely phrased, with good tone and attention to dynamics.

Darrell Fancourt recorded the eponymous role in The Mikado three times: in 1926, 1936, and 1950. Each subsequent time, his cackles of laughter grew more grotesque. Here he’s at his freshest, and most involved. That he can hold his own against the likes of Lewis says much for Fancourt’s ability to project character. (His “amateur tenor whose vocal villainies” is especially funny, and sounds perhaps intentionally a bit like Oldham’s Nanki-Poo). Pish-Tush is taken by George Baker, who only once sang G& S professionally in his 53-year career. He was often called upon for recordings of the operas, however, given his fine voice, strong enunciation, and perfect feel for the style. His “Our great Mikado” is rightly celebrated.

There are a few flubs in the orchestra, but Harry Norris conducts with a flexible, singing line that never becomes too lax. His overture is one of the most attractive on disc, with good attention to rhythms, and a refined control of tempo. He also gets more out of the “with passion tenderer still” line than I’ve heard elsewhere, with rapt singing from the chorus.

There’s no dialog, and none would be commercially recorded for The Mikado until Columbia’s release of the abridged version aired on The Bell Telephone Hour in 1960, featuring Groucho Marx, Helen Traubel, Stanley Holloway, and Robert Rounseville. Be advised, the original opera’s use of the term “nigger” can be heard twice, before it was tactfully changed in performing editions after 1947. It’s a wince-worthy two-by-four between the eyes. You have been warned.

Mark Obert-Thorn’s transfers are excellent. I’ve lived for years with Pearl GEMM CDS 9025, an LP transfer that employed minimal filtering, and was scratchy as a result. Obert-Thorn’s comes as a distinct relief, in A/B comparison: the scratchiness reduced, yet with more details present, and a sometimes surprisingly open room ambiance (as in the orchestral passage leading to the glee, “Brightly dawns our wedding day”) and tonal variety (as in the second verse, “If I’d a fortune,” to “See how the fates”). This is an impressively listenable achievement.

Minimal liner notes are provided, but frankly, that doesn’t matter. This Mikado remains one of the best available, with energy, ensemble feel, and a real flair for the theatrics. It presents some of the celebrated legends of G& S performance in the early decades of the last century, and in this new remastering, doesn’t shred the ears. Strongly recommended.

Barry Brenesal

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:6 (July/Aug 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.