This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Synopsis

Honegger's dramatic oratorio in a fine Philadelphia recording from Ormandy

"A beautiful American performance (in French) on finely engineered records" - Gramophone

This work was commissioned and first performed by Ida Rubinstein, the dancer who had previously commissioned Ravel to write Bolero. It's appropriate, then, that the narration in this recording is performed by Vera Zorina (born Eva Brigitta Hartwig in Berlin), an accomplished ballerina and later Hollywood actress who married George Balanchine and who, at the time of this recording, was married to Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson. Her participation in this recording was not mere nepotism, however. She had not only performed the role of Joan in the U.S. premiere (in 1948 with Charles Munch and the New York Philharmonic), but had also participated in every subsequent performance in North America up to the time of this recording. For his part, Ormandy's association with Honegger dated at least from his Minneapolis days in the early 1930s, when he had recorded the composer's Concertino for Piano and Orchestra.

The present transfer was made from the best portions of two first edition blue label American Columbia pressings. There are some instances of distortion, dropout and studio noises which are on the original LP master tape.

Mark Obert-Thorn

HONEGGER Jeanne D'Arc au Bûcher (Joan of Arc at the Stake) [notes]

Dramatic Oratorio - Text by Paul Claudel

First issued on Columbia SL-178

Recorded 16 November and 21 December 1952 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Speaking Roles

Jeanne d’Arc Vera Zorina

Frère Dominique Raymond Gerome

Singing Roles

The Virgin Frances Yeend (soprano)

Marguerite Carolyn Long (soprano)

Catherine Martha Lipton (contralto)

A Voice; Jean de Luxembourg; Regnault de Chartres; Porcus; First Herald David Lloyd (tenor)

Guillaume de Flavy; A Voice; Second Herald Kenneth Smith (bass)

Narrators: Anne Carrere, Charles Mahieu, Jean Julliard, John H. Brown (boy soprano)

Temple University Choirs (Elaine Brown, director)

St. Peter’s Boys Choir (Harold Gilbert, director)

Eugene Ormandy · The Philadelphia Orchestra

Recorded in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 1952

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

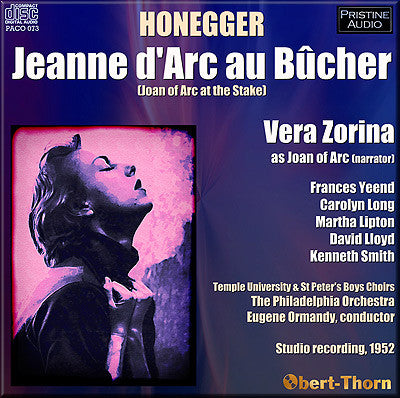

Front cover artwork based on a photograph of Vera Zorina as Joan

Total duration: 72:12

Prologue

The chorus sings of the great darkness that had enveloped France, and how God sent Joan to unite the people.

I The Voices from Heaven

A heavenly chorus summons Joan.

II The Book

A Dominican friar calls

for Joan, who appears in chains. In a spoken dialogue, he expresses

sympathy toward her fate, and revulsion toward those who condemned her.

He offers to read to her from a book which details her trial.

III The Voices of the Earth

The

charges against Joan are voiced by Frère Dominique and the chorus. Joan

cannot understand why the priests she revered and the people she loved

turned against her. Frère Dominique likens her accusers to beasts.

IV Joan Given Up to the Beasts

In a surreal scene, Joan’s accusers are portrayed as various animals. The main judge is a pig (Porcus in Latin, for cochon

in French standing for Cauchon, the name of the judge at the actual

trial). The jury members are sheep and the recording secretary is an

ass. Joan’s testimony is twisted around by the court, and she is

sentenced to die at the stake.

V Joan at the Stake

Joan hears the

names she is being called – heretic, sorceress, apostate, barbarian –

while at the stake awaiting execution. She asks Frère Dominique how

things came to this. He explains that it was due to a card game invented

by a mad king.

VI The Kings, or the Invention of the Game of Cards

The

Heralds explain the Hundred Years’ War as a game of cards bearing the

likenesses of various nobles on either side of the conflict as well as

the Deadly Sins and Death itself. The kings neither lose nor win, but

only change places. In the end, Joan is delivered up as a pawn.

VII Catherine and Margaret

The

tolling of her death knell reminds Joan of the church bells of her youth

and the voices she heard from St. Catherine and St. Margaret, voices

that urged her to take up a sword and escort the King of France to

Rheims for his coronation.

VIII The King Sets Out for Rheims

The

people are assembled for a mid-winter festival. Heurtebise and his

wife, Madame Tonneaux, personifications of bread and wine, sing of their

reunion after a long separation. A cleric interrupts the celebration to

lead the people in a Latin hymn which parallels the wait of the

Isrealites for the Messiah to appear with the expected arrival of the

King of France. Suddenly, the King is sighted. Joan claims with pride

that she brought this about, leading the reluctant King to Rheims. Frère

Dominique counters that it was God who brought this about, and

pointedly asks Joan whether it was for an earthly king that she gave her

life.

IX The Sword of Joan

Once more, Joan

recalls her younger days, and the voices she heard from the saints.

Frère Dominique asks her to explain her sword. Joan recounts the songs

children would sing to welcome the month of May. She talks about how in

the wintertime, it would look as though all nature was dead and hope had

gone; but in the spring, hope would rise anew. She says that the sword

St. Michael gave to her is not named Hatred, but rather Love. Her voices

told her to take the sword and go to Rouen, where she would ultimately

die, on horseback in May.

X Trimazo

Joan reprises the

childrens’ song about the month of May, adding that she will become a

candle to light at the feet of the Virgin.

XI The Burning of Joan of Arc

The

people cry for Joan’s death. Frère Dominique has gone, and she is now

alone. A priest demands that she sign a confession, but she refuses to

lie to save herself. The voice of the Virgin tells her to trust in the

fire for her deliverance. As the flames mount, the saints join with the

Virgin to welcome her, and the chorus’ attitude changes to one of

praise. Joan breaks the chains she has been wearing throughout, and

proclaims as she dies that joy is the strongest, love is the strongest,

God is the strongest. The chorus ends by singing, “No one has a greater

love than one who gives his life for those he loves.”

Mark Obert-Thorn

Fanfare Review

Lay your hands forthwith on this stunning performance, which has my highest possible recommendation.

Arthur Honegger’s Jeanne d’Arc au Bûcher is not an oratorio in the traditional sense. Its actual structure is that of a dramatic dialog for two main characters with spoken parts, Joan of Arc and Brother Dominic, underlaid by musical accompaniment and punctuated by scenic episodes for occasional vocal soloists, chorus, and orchestra. Joan, bewildered by her condemnation as a heretic and sorceress by a church tribunal and by her sentence of burning at the stake, asks the monk Dominic as she is brought to her execution to show her how she has sinned, so that she might confess and repent. What unfolds instead—with macabre and biting irony—is a complete vindication of Joan and condemnation of her enemies and accusers, with Dominic making it clear in passing that he, too, has suffered injury due to his evident sympathy for Joan. As Joan is executed, heavenly voices make clear her exoneration and reception into Heaven.

Despite Joan’s legendary fame—extending to several major Hollywood versions of her life as well as Tchaikovsky’s substantial but all too little-performed opera Orleanskaya Deva (The Maid of Orleans)—the story of her life and death remains deeply rooted in French national sensibilities. For many Frenchmen, she is far less important as a Christian saint than as an iconic symbol of French nationalism and foe of foreign oppression. Her formal canonization in 1920 was not just a long-overdue recognition by the Magisterium of Joan’s spiritual character upon the 500th anniversary of her birth, but was also bound up with a complex, multifaceted political settlement between the Vatican and the thoroughly secular government of the Fourth Republic. Honegger’s composition of his oratorio not long afterward, in 1935, must be considered against that backdrop; like Ralph Vaughan Williams he often turned to biblical and theological texts for major choral works despite not being a practicing Christian. Also like his British counterpart, such peculiar sensibilities have meant that such works have tended not to travel beyond the boundaries of his native land.

Except for the “Organ” Symphony and various concerti of Camille Saint-Saëns, and certain pieces by Debussy and Ravel, Eugene Ormandy was not associated with French repertoire, much less anything as formidable as the music of Honegger. It has become all too easy to forget that, before Ormandy in his later years settled into a comfortable routine repertoire of the German and Russian Romantics plus Sibelius, with occasional forays into Bartók, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich, he regularly explored contemporary repertoire, with names such as Norman Dello Joio, Vincent Persichetti, Walter Piston, William Schuman, and even Krzysztof Penderecki (Utrenja!) represented in his discography. Thus, it should come as something less than a total surprise to discover that Ormandy recorded Honegger’s “dramatic oratorio” for Columbia in 1952—especially since Ormandy also recorded Honegger’s Piano Concertino, with pianist Eunice Norton and the Minneapolis Symphony, back in 1934. The score is also one that would have appealed to Ormandy’s musical sensibilities; despite the occasional use of an ondes Martenot for special effects, overall the thematic and harmonic vocabulary is more romantic and less astringent than in the composer’s symphonies.

Even so, I confess that I was somewhat skeptical when I received this disc for review, after I had passed up an initial opportunity to select it. Honegger, Ormandy, a cast of non-French and lesser-known singers, recorded in monaural Columbia LP sound, hardly seemed to promise an enticing combination. Seldom have I been so delighted to have my expectations confounded! This is a terrific performance that I have immediately shortlisted for my 2012 Want List. Ormandy leads a crackerjack account of the score, roiling by turns with dramatic tension, seething sarcasm, and ethereal beauty; the playing of the “fabulous Philadelphians” fully lives up to that moniker. More unexpectedly, the two well-drilled choirs sing with excellent French diction as well as fine ensemble. Equally surprising is the riveting effectiveness of the protagonists in the two main speaking roles. Vera Zorina (1917–2003) was not primarily an actress, but a ballerina; her actual name was Eva Brigitta Hartwig and she was born and raised in Berlin. She was first the mistress of choreographer Leonide Massine, and then successively the wife of choreographer George Balanchine and of Columbia record producer Goddard Lieberson, who cast her in this recording. If her Joan is more powerful and less maidenly than one might stereotypically expect, one only need recall that the original Joan led an entire army while clad in a suit of chainmail armor to correct that supposition. The Belgian actor Raymond Gerome (1920–2002) makes for a distinguished and sympathetic Brother Dominic.

Another unanticipated but welcome surprise is the caliber of the vocal soloists, all of whom turn in first-rate work. This was not unexpected regarding tenor David Lloyd, an exceptional and greatly underappreciated singer whose career was cut short by a head injury suffered in a stage accident; here he covers no fewer than five different parts, including that of Porcus in the farcical trail of Joan by a court of animals, with masterly facility. However, the competent but not exceptional recordings of soprano Frances Yeend under the baton of Bruno Walter (a Beethoven Ninth Symphony and Bruckner Te Deum) did not prepare me for her outstanding assumption here of the treacherously high-lying role of the Virgin Mary, dispatched on pitch with securely even vibrato and sweetness of timbre. No less capable are soprano Carolyn Long and contralto Martha Lipton as Saints Margarite and Catherine, and bass Kenneth Smith in a trio of cameo roles. Three other small spoken parts are also well filled; only one line sung by a boy soprano falls somewhat short of the superlative standard set by all the other participants. I compared this recording head-on with that on Supraphon under the baton of Serge Baudo, whose cycle of Honegger’s symphonies still remains the touchstone for those works. While Baudo scores points for superior recorded sound and consequent greater clarity of orchestral detail, Ormandy and his forces are runaway winners in every other category, above all in the quality of the vocal soloists, with those under Baudo being uniformly poor.

Finally, special note should be made of Pristine’s remastering of this performance, undertaken by noted sound restoration expert Mark Obert-Thorn. One always expects top-flight results from Obert-Thorn, but considering that he was working here from two sets of early Columbia blue-label LPs, with their noisy surfaces, constricted but harsh treble frequencies, and tepid but murky bass range, the results are well-nigh miraculous. The sound now has body and bloom to it; deficiencies on the treble and bass ends of the spectrum have been skillfully corrected to the extent possible; distortion has been eliminated or minimized; the orchestra and chorus sound reasonably natural and full. That the chorus should emerge from a Columbia recording of this vintage with such clear French diction is nothing short of astonishing. As I was not sent the ambient stereo remastering, I cannot report on how much better yet the sound may be on that. The only drawback to this release is, as is typical for Pristine, the absence of a libretto (indispensable for this work) and detailed program notes (those provided online offer little more than a brief plot summary). But don’t let that be an impediment in this instance; find a copy of a libretto elsewhere and lay your hands forthwith on this stunning performance, which has my highest possible recommendation.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:2 (Nov/Dec 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.