This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

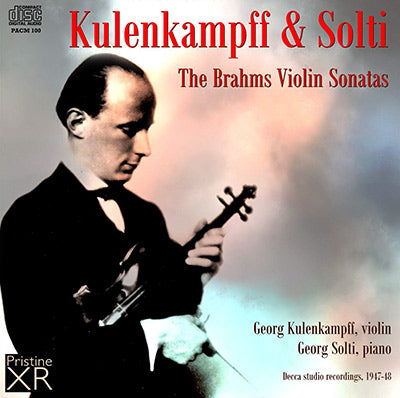

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

Kulenkampff and Solti fabulous in Brahms' three violin sonatas

One glittering career closes and another begins in these superb new XR-remastered transfers

These delightful sonatas combine Kulenkampff's last recordings before his unexpected and sudden death in 1948 at the age of 50 with Georg Solti's very first of a fifty year career. Here Solti's role is as piano accomapanist, rather than the legendary conductor he would become, yet his innate musicality shines through. Kulenkampff, meanwhile, was one of Germany's finest violinists and would have expected many more years of a glittering career.

They were recorded at the tail end of the 78rpm era, and whilst this

XR remastering has brought out wonderful tone from both players, there

were difficulties at times with surface noise, most particularly in the

second sonata. By contrast much of the first and third sonatas proved

clean and clear, and the sound quality in these is frequently

astonishing.

Andrew Rose

-

BRAHMS Violin Sonata No. 1 in G, Op. 78

Recorded 28 January 1947, Radio Studio, Zurich

Matrix nos. ARS.76-81

Issued as Decca 78s K.1705-07

-

BRAHMS Violin Sonata No. 2 in A, Op. 100

Recorded July 1948, Radio Studio, Zurich

Matrix nos. SAR.346-51

Issued as Decca 78s AK.2083-85

-

BRAHMS Violin Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108

Recorded July 1948, Radio Studio, Zurich

Matrix nos. SAR.362-67

Issued as Decca 78s K.2112-14

Georg Kulenkampff, violin

Georg Solti, piano

Sonata No.1

The recording balances well the piano both aloft and slow. Perhaps its tone is a shade dry, but that presumably is the player’s affair. I do not know either of the two at “first ear.” The violin is always finely outlined, with a tense strength that for me is a shade restrained.

The first sonata did not come out until Brahms was well on in years (1878-9); it was the product of a happy summer holiday. The sensibility is sweet, tender, strong, yet never loudly outspoken. The players give us all the requisite strength, without very notable tenderness. It is a wee bit sober: but then, it can be argued, Brahms did not spill over. Yet he might have been treated a trifle more smilingly. In the development there is splendid partnership and aplomb. I think the violinist could make rather more of that opening phrase, which so pervades the work. He is very true and pure in tone, if not extremely warm. The playing is shapely, strong, and such as I think Brahms would have approved.

There is a phrase employment in the second movement (as the start was used, in the first): that opening rise and fall; we find it also in the finale. Here is an essence of Brahms’s nobility. Throughout the work he sings gloriously. The agitation is almost confined to the first movement. The end of the slow one is exquisite; the pressures of the middle part soothed and endeared. Finale: The theme is derived from two songs, Regenlied and Nachklang (Nos. 3 and 4 of Op. 59), both of which begin alike, but continue differently, as do the attacks in the sonata. There is an obvious connection with the first theme of the first movement. Then, too he uses his slow movement theme in this one. The sonata gets its nickname, Rain, from the prevalence of this figure, and perhaps of the idea of gently pattering rain—not in a sorrowful sense, but as a mood and colour element, and to some extent a unifying one in the three-movement work. The work of the partners in this sonata is particularly apt, neat, gracious, without the least sentimentality: with perhaps, as I suggested, even a trace of dryness that does not at all connote dullness: rather it is the opposite of sweetness, as in wine. There is a curious little inward withdrawnness in the finale, I feel: very typical Brahms, musing happily, self-contained, always solitary, yet the philosopher who cannot demand love, only offer it sullenly.

A. R. - The Gramophone February 1948

Sonata No. 2

A very charming interpretation of a sonata which is predominantly lyrical and suffers a little from lack of contrast. The least successful movement is the middle one in which Brahms attempts to combine slow movement and scherzo and falls between two stools. Balance between the two instruments is good but there is a serious lack of the fundamental bass all the way through and, on my copies, rather too many clicks on sides 2, 4, and 5. I mention these not because they disturb me in the least but because I know such blemishes upset those who demand that schoolgirl complexion.

A. R. - The Gramophone March 1949

Fanfare Review

There is huge joy to be gleaned from this release ... Fabulous

This is a fascinating chamber pairing. The young Georg Solti, long before the knighthood, making his first recording, and on the piano at that. These are Decca 1947–48 mono recordings, and as is its wont Pristine Audio offers a variety of ways of auditioning these performances: mono or stereo, mp3 ambient stereo, FLAC (24-bit or 16-bit Ambient Stereo or mono 16-bit), or good old compact disc to your door. They are taken from Decca 78s (not that you’d guess it). The First Sonata was taken down on January 28, 1947; the other two in July 1948, all three in “Radio Studio,” Zurich.

Many a collector of vinyl has a huge fondness for Decca recordings of this period, of course. Rightly so, for the recording quality those engineers could extract from their sound sources were legendary. Producer and XR remastering engineer Andrew Rose has given us the perfect Brahmsian gift here. The original producer, I believe, was Victor Olof. Kulenkampff’s wiry top is nowhere uncomfortable, and in fact in the first movement, prior to the pizzicatos, it is positively glorious; and we can clearly hear the expressivity of his middle register, the latter right from the very opening paragraph of the First Sonata. There’s an important point here: These are not the most burnished of performances, and this turns out for the music’s benefit. Both players honor Brahms’s lyricism without creating dense forests of sound. Clarity of texture is clearly the watchword, as is febrile intensity. The bass of Solti’s piano at the opening of the slow movement is beautifully rendered across all media, while Kulenkampff’s deeply expressive cantabile is highly touching. The two create a sense of profound stillness at several points that perhaps was often to elude Solti in his later baton years. Kulenkampff injects some very characterful phrasing into the finale; perhaps Solti is more leaden here, more the dutiful accompanist. The close of the First Sonata is simply beautifully managed.

The piano sounds a little muffled at the opening of Sonata No. 2, and the music can occasionally sound as if it is heading towards distortion (it never actually gets there, though the sound becomes more raw). Kulenkampff’s violin is still well caught, though, his sweet upper register sounding beautiful against Solti’s gently articulated higher-register chords. Elsewhere Solti’s chords can plod somewhat, but the rapport between the two instrumentalists remains clear, especially in the central movement, where some gossamer articulation from both graces the Vivace sections. The finale, too, holds magic, not least in Solti’s mezza voce spread chords. Ensemble between the two is faultless. One senses not only the emotional play, but also the sheer genius of the music’s construction at every point. There is a little muddying in the piano sound in this finale, alas.

The Third Sonata has a rugged strength to its first movement, a palpable strength of Brahmsian struggle that seems most apt. Some violinists might have warmer low registers for the opening paragraph of the slow movement, but Kulenkampff’s eloquence bows to none. Perhaps Solti’s accompaniment is, in comparison, just a tad pedestrian, but as the movement progresses the two minds meld. The shifting rhythms of the third movement are a real high point of this release, Solti’s touch being notably flighty. The recording captures Kulenkampff’s pizzicato well, too, in the third movement, while the agitato indication of the finale is perfectly judged.

There is huge joy to be gleaned from this release. By far the vast majority of reviews of Kulenkampff on the Fanfare Archive are of his concerto recordings, so this example of his glorious chamber music abilities is doubly welcome. There is a shedload of recommendable performances elsewhere in the catalog (for the record I fully concur with ArkivMusic’s choice of Krysia Osostowicz and Susan Tomes, now on the cheaper Helios side of Hyperion, 55087; Anne-Sophie Mutter with either Weissenberg or Orkis is another fine interpreter; and that’s without delving into other historical releases). But for its historical importance, its sound (despite my minor grumblings) and for the integrity of interpretation, this is an issue that demands to be heard. That Pristine Audio offers a choice of price points and methods to do so is a bonus given to us by modern technology. Fabulous. Colin Clarke