This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- New tab

- Full Track Listing

- New tab

- Historic Review

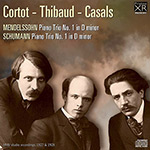

Cortot, Thibaud and Casals - perhaps the greatest piano trio ever?

Their Mendelssohn and Schumann trios sound stunning in these new XR remasters

By the time of these recordings, Cortot, Thibaud and Casals had been playing together as a trio for around twenty years, and at a time when chamber music was considered by some as a bit of a joke they were clearly regarded as anything but. Each, of course, was a well-established solo musician in his own right, but I think it's fair to say they were one of the first superstar trios of the age of sound recording. The development of recorded chamber music had been aided by the formation in the late acoustic era of the National Gramophonic Society by the publisher of The Gramophone, and this clearly spurred the major record companies into following suit (the NGS fizzled out in 1931 as a result of seeming no longer necessary for precisely this reason).

Although microphone and electrical recording technology, introduced in the summer of 1925, was still very much in its infancy when these two recordings were made, it's quite astonishing to hear the fidelity and detail captured in both the 1927 Mendelssohn and the 1928 Schumann. XR remastering has, here, done great service to the tonal qualities of all instruments, with the cello and piano being particularly well-served. At the same time, Capstan pitch stabilisation processing has brought a real solidity to the recording. Surface noise was less of an issue with the Mendelssohn than the Schumann, where the slightly increased frequency range of the recording clashed at times with surface swish, though this has been largely dealt with. The results are particularly splendid!

Andrew Rose

-

MENDELSSOHN Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49

Recorded Large Queen's Hall, London, 20 & 21 June, 1927

Matrix Nos. CR .1385-2, 1936-2, 1387-1, 1389-1, 1390-2, 1391-3, 1392-2, 1393-1

First issued as HMV 78s DB.1072-75 -

SCHUMANN Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 63

Recorded Studo C, Small Queen's Hall, London, 15 & 18 October and 3 November, 1928

Matrix Nos. Cc.14740-2, 14741-1, 14742-1, 14743-1, 14744-3, 14756-1, 14757-1, 14758-3

First issued as HMV 78s DB.1209-12Alfred Cortot piano

Jacques Thibaud violin

Pablo Casals cello

Schumann Piano Trio No. 1, 78rpm release

Again

the Great Three—Cortot, Thibaud, and Casals—and, alas, Uncle Red Label

and all. H.M.V., 1209-12, costs 34s., for the Schumann Trio in D minor,

Op. 63 (first movement, three sides ; second, one ; other two movements,

one record each). There is grand meat in the first movement, in which

the appassionato is finally brought out, not merely laid on. Try the

last half-inch of the first side for a draught of the purest

romanticism—that lamentable commodity which, a few dotermined persons

assure us, with ludicrous lack of effect, is going , . . going. ... I

find the strings sometimes a bit too keen for my taste. Hear how they

work joyfully, like Titans, in the second movement, a great hurdler, in

which strings and piano have an attractive rhythmic scheme between them.

The piano dims in the third movement accompaniment to the fiddle. That

opening is an unusual one, piquing curiosity as to what is coming after.

A very rich, calm piece it is—the inward eye of Schumann. This

movement, by the way, runs straight on into the last, a big, broad

swinger, full of heart and devices for beguiling the way. The whole work

is on a high level, with few drops—some of the best of Schumann’s

writing for a few instruments; but I feel that in this strongly-nerved

recording, the strings, whether by reason of natural vigour or the

microphone’s interference, are a bit too strong for the piano.

W. R-A., The Gramophone, April 1930

Fanfare Review

If you don’t know these performances, I recommend them with all urgency

Anyone interested in chamber music needs to know the playing of the Pablo Casals, Alfred Cortot, Jacques Thibaud trio. Star soloists of their time, they had worked together for around 20 years when they made these, and a handful of other vibrant, musically probing recordings in the late 1920s. We’re lucky that they were around for the advent of microphone and electrical recording technology in 1925, but it’s a great shame that they didn’t record more as a trio; examples of their Brahms, more Schumann trios, French repertoire, would be invaluable.

Their Mendelssohn D-Minor is high on the list of outstanding recordings of that perfect work, from any era, but their Schumann D-Minor is even more extraordinary. It’s a much less straightforward piece than the Mendelssohn, far less often played, and the group penetrates to the heart of its unsettled, often despairing emotional world. Their performance communicates the volatile, depressive mood of the first movement, the frustrated defiance of the second, and the mournful, interior musings of the third. In the fourth movement, Schumann resolves the conflicted state of the previous three with a restoration of melodic coherence. I believe that its Mendelssohnian main theme is an intentional homage to that composer, Schumann’s great friend who died in November of 1847, the year in which Schumann composed both his First and Second trios.

What I love about the Casals-Cortot-Thibaud Trio is their vivid characterization of the music, achieved through varieties of tone color, and the kind of spontaneous sounding flexibility in phrasing that’s much more often heard from a soloist than a chamber ensemble. Cortot holds the ensemble together with the subtlety of the balances that he achieves with the strings. I can’t think of a pianist in chamber music who was gentler in his quiet playing—try the opening of the Mendelssohn scherzo—or more imaginative in matters of color or rhythmic energy. And what glorious string playing is captured in these recordings: The forthright, singing voice of Casals’s cello playing, and Thibaud’s artfully varied vibrato and, to my ears, always welcome portamentos. Technical virtuosity and seamless ensemble, the end goals of many modern piano trios, are just the starting point for these artists.

My first acquaintance with the Schumann Trio came via this performance on an aged RCA LP, in which it was coupled with the Schubert Trio No. 1. When I first heard the spooky sounding passage for ponticello strings in the first movement, I thought that either a distant AM radio station was somehow interfering with the record, or that there was a large amount of dust on the needle. Neither turned out to be the case; both the recorded sound of the performance and its transfer were simply quite poor. Pristine prints a 1930 Gramophone review of the Schumann, and I agree with “W.R.A” that “in this strongly-nered recording, the strings, whether by reason of natural vigour or the microphone’s interference, are a bit too strong for the piano.”

Even in Andrew Rose’s restoration, this problem with the original miking can’t be altered. The strings, especially the violin, sound a bit strident at louder dynamic levels, and the piano sound is too distant, but Rose’s reduction of surface noise, and some pitch correction, make it easier to listen past the original recording’s flaws to experience a transcendent performance. The Mendelssohn had better sound to begin with. If you don’t know these performances, I recommend them with all urgency. Paul Orgel