This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

A Sea Symphony of Ralph Vaughan Williams was the composer’s first large-scale composition to receive a public performance and subsequent publication. (Two unpublished predecessors, also for vocal soloists, chorus, and orchestra, that have emerged from manuscripts only in recent years areThe Garden of Proserpine from 1897–99 and A Cambridge Mass from 1901, the latter submitted for the D.Mus. degree at Cambridge.) RVW began work on the score, originally envisioned as a cantata titled Ocean, in 1903 or 1904; in her biography of her husband, Ursula Vaughan Williams mentions that he was working on it during a 1904 vacation in Yorkshire. In 1906 he wrote to Gustav Holst that the scoring of the second movement was done, and the whole was completed in 1907, though revisions would be made right up to its premiere. Influences upon it include the cantata Invocation to Music of his revered teacher, C. H. H. Parry; Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius; and Sea Drift of Frederick Delius. (During his studies with Ravel in 1907, RVW hunted down Delius in Paris and played the entire work for him, eliciting the laconic rejoinder, “Vraiment, il n’est pas mesquin”—Truly, it is not shabby.)

The premiere was given at the Leeds Music Festival on 12 October 1910, RVW’s 38th birthday, with the composer on the podium. The soloists were soprano Cicely Gleeson-White and baritone James Campbell McInness; the renowned dramatic soprano Agnes Nicholls (wife of Hamilton Harty), whom RVW originally had in mind in writing that solo part, would sing with McInness in subsequent performances elsewhere. Despite the now famous words of encouragement from timpanist C. A. Henderson—“Give us a square four-in-the-bar, and we’ll do the rest”—RVW was diffident as to how the initial performance went, even describing it in a 1941 letter as “a complete flop.” Aside from his own lack of sufficient experience as a conductor, it certainly could not have boosted his confidence when a nervous McInness said to him, “If I stop, you’ll go on, won’t you?” In fact, though, reviews were quite positive. Herbert Thompson of the Yorkshire Post perceptively observed, “The music is difficult, unnecessarily so, one would imagine, for probably the desired effect might have been obtained with less complication and fewer awkward passages, but however this may be, it strikes one as sincere, highly poetic in feeling, and showing the power to deal with a big canvas. The ideas are never puny or finicking, and the music has breadth and grandeur….” The critics for the London Times and Manchester Guardian were even more enthusiastic, without reservations. Thanks to championing by Hugh Percy Allen (1869–1946), who in 1918 both succeeded Parry as a professor of music at Oxford and became director of the Royal College of Music in London, the symphony had further performances at Oxford in 1911 (which RVW found far more satisfactory) and London in 1913. But it was a 19 June 1919 performance, directed by Allen for presentation of an honorary Oxford doctorate to the composer, that is often considered to have established the work in the standard repertoire in England.

The subsequent success of A Sea Symphony was also due in no small measure to the advocacy of Sir Adrian Boult (1889–1983). As an undergraduate at Oxford he came under the tutelage of Allen; he sang as a chorister in a performance of Toward the Unknown Region in 1909, attended the first two performances of A Sea Symphony, and was introduced to RVW in 1912. Boult conducted the symphony himself beginning in 1924, and assiduously promoted it thereafter; at a 1930 London performance, RVW’s first wife Adeline wrote to a friend, “Adrian Boult must be overworking, he is nothing but a black streak in a white waistcoat….” During his 20 years as director of music at the BBC, Boult used his position to promote the music of English composers, above all Elgar and Vaughan Williams. While the two men were not close personal friends, their relationship was more than cordial. To this day, Boult remains the unrivalled champion of RVW’s music on disc, with over 60 recordings of 36 different works that includes two complete cycles of the nine symphonies, with the present 1953 recording coming from the first cycle. Fittingly, on 20 February 1983, two days before his death, Boult asked his wife to play for him his second, stereo recording of A Sea Symphony; it was the last music he was to hear in this life.

notes by James Altena

The genesis of Vaughan Williams’s “London” Symphony, as recounted twice by the composer (in his essays “A Musical Autobiography” and “George Butterworth”) is well known. One day in 1910, Butterworth “said in his gruff, abrupt, manner: ‘You know, you ought to write a symphony.’ I answered, if I remember aright, that I had never written a symphony and never intended to.” As RVW admitted, “This was not strictly true”—twice before he had drafted movements of projected symphonies, “all now happily lost. I suppose that Butterworth’s words stung me” and in 1912–13 he worked up sketches originally intended for a symphonic poem into the symphony. It seems, then, as if he initially considered A Sea Symphony to be an extended secular cantata, and the “London” Symphony his first proper symphony. He showed his work to Butterworth as it progressed, “and it was then that I realized that he possessed, in common with very few composers, a wonderful power of criticism of other men’s work and insight into their ideas and motives. I can never feel too grateful to him for all he did for me over this work.” After Butterworth died in combat in World War I, RVW dedicated the score to him. In his old age he declared it to be his favorite among his own symphonies.

Geoffrey Toye conducted the premiere with the Queen’s Hall Orchestra at its home venue on Friday, March 27, 1914. Critical reaction was overwhelmingly laudatory; the critic for the Dorking and Leatherhead Advertiser declared that it was “not only the most masterly, but also the most beautiful work, musically or psychologically considered, from the pen of any musician of his generation that we have heard in recent years”; that for J. P.’s Weekly opined that it was “a symphony that is full of noble and unforgettable music.” There were a few dissenting voices; reviews in the Globe and Truth were tepid, while H. A. Scott for The Westminster Gazette dismissed it outright as “for the most part very dry and labored … dull in the extreme.” Most writers rightly grasped that the symphony was intended to be psychologically evocative of states of mind in beholding aspects of London, rather than graphically pictorial in the manner of a symphonic poem; in RVW’s own words it was a “work written solely in music and meant to appeal solely to the musical imagination of the hearers.” The Lento was singled out for its particular beauty. Several critics agreed that the finale was the weakest link and would be improved by being shortened. In the two bouts of revisions that RVW undertook in 1918–20 and 1933 he pruned that movement considerably, resulting in the version generally familiar today, though both the original 1913 and intermediate 1920 scores have also enjoyed recordings.

The “Pastoral” Symphony was composed in the aftermath of the war in 1919–20. This work often is alleged to have prompted Peter Warlock’s famous gibe that RVW’s music “is all just a little too much like a cow looking over a gate” (in fact Warlock had high praise for this symphony). This gave rise to the derisive nickname of “Cow Pat” school (coined by Elizabeth Lutyens in 1950) for the so-called “English Pastoralist” composers such as RVW, Butterworth, Finzi, Ireland, and Moeran. But the composer himself wrote in 1938 to Ursula Wood that the score “is really war time music … it’s not really Lambkins frisking at all as most people take for granted,” an embodiment of his reminiscences of fields in France where he served in the war as a medical orderly, and an elegy to those who fell there in combat. The famous trumpet tune in the second movement provided an initial idea for the work when a regimental bugler accidentally played an interval of a seventh instead of an octave.

The premiere was given by Adrian Boult on January 16, 1922, with the London Philharmonic and soprano soloist Flora Mann. Most critics seem to have been a bit nonplussed by the score’s sustained, subdued mood throughout its four movements; Ernest Newman penned a sour diatribe against it for The Sunday Times. Only recently have its many virtues gained proper appreciation; the present recording was its premiere on discs.

JAMES ALTENA

Composed in 1931–34 and dedicated to Arnold Bax, the Fourth Symphony of Vaughan Williams notoriously represents for many listeners a bewildering departure from his usual compositional style. Although fellow composers waxed enthusiastic – William Walton supposedly said that it was “the greatest symphony since Beethoven” – critical reception was far cooler. Writing in The Manchester Guardian on April 11, 1935, the day after the premiere, Neville Cardus opined: “Vaughan Williams is becoming an enigma. A few years ago he was one of our purest melodists, drawing his simple accents from English folk-tunes. To-day he is everything but a melodist. His new symphony, played superbly to-night by the B.B.C. Orchestra under Dr. Boult, has many admirable orchestral qualities, but a man might as well hang himself as look in the work for a great tune or theme…. I decline to believe that a symphony can be made out of a method, plus gusto.”

The Fourth represents a departure from the essentially poetic and discursive veins of RVW’s first three symphonies: It is far more taut and abstract, more academically rigorous in its formal procedures, as well as far more jagged and bitingly dissonant in its thematic contours and harmonics. As in the Piano Concerto from 1926–31, one hears the composer grappling with the compositional idioms of Bartók and Hindemith. The score’s “meaning” remains controversial. Its blazing fierceness often later would be seen as prophetic of the catastrophes of totalitarianism and war soon about to engulf Europe. In an October 1958 essay in the Musical Times, Boult asserted that RVW “foresaw the whole thing [i.e. war] and surely there is no more magnificent gesture of disgust in all music than the final open fifth when the composer seems to rid himself of the whole hideous idea.” But in a letter from December 1937, RVW denied such associations: “I wrote it not as a definite picture of anything external – e.g. the state of Europe – but simply because it occurred to me like this.” On the other hand, RVW’s biographer Michael Kennedy saw the work as “a kind of self-portrait: the towering rages of which Vaughan Williams was capable, his robust humour, his poetic nature,” and a friend wrote to RVW after the premiere that “I recognized your poisonous temper in the scherzo.” Perhaps the best and last word is the composer’s exasperated rejoinder, “It never seems to occur to people that a man might just want to write a piece of music.”

The Fifth Symphony, composed between 1938 and 1943, is the Fourth’s antipode in spirit and temperament, though structurally both works employ cyclical forms, with the finales bringing back materials from the opening movements. However, rather than reverting back to the style of the first three symphonies, the Fifth instead moved forward to break new ground as one of RVW’s most spiritually profound works. The composer had been laboring since 1906 on an opera based on John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress; doubtful of its completion (he would finally finish it in 1949), he recycled some of its materials into music for a dramatic radio presentation and this symphony. Although not printed in the published version, the manuscript of the Romanza third movement that forms the heart of the work quotes the following lines from Bunyan’s work: “Upon that place there stood a cross, And a little below a sepulchre … Then he said, ‘He hath given me rest by his sorrow and Life by his death.’” Frank Howes, writing in The Times on 25 June 1943, the day after the premiere under RVW’s baton, rightly discerned that the work is “therefore essentially apocalyptic, but in the only way possible to the composer, that of quiet contemplation, not of a sudden or dramatic revelation. It seems to absorb into itself and sum up all that he has ever written, and to give us a restatement of his whole philosophy now proved by life’s experience. It is not too much to say that this belongs to that small body of music that, outside of late Beethoven, can properly be described as transcendental.” Due to wartime difficulties in communications, the score’s frontispiece reads, “Dedicated without permission to Jean Sibelius.” Boult subsequently secured Sibelius’s consent, and after hearing a broadcast performance the Finnish composer wrote: “This Symphony is a marvelous work.... The dedication made me feel proud and grateful.”

JAMES ALTENA

As is well known, Vaughan Williams created his Sinfonia antartica out of the film score he created for the 1948 film Scott of the Antarctic. Greatly moved by its subject matter, the composer actually wrote some 996 bars of music before receiving the actual film script. Only about half of that music made its way into the film, but RVW was by then already contemplating writing a symphony with the whole. Due to work on other projects, notably completion of his opera The Pilgrim’s Progress after 45 years’ gestation, the symphony was not finished until early 1952. RVW dedicated it to Kelville Ernst Irving (1878–1953), the veteran theater director and music director at Ealing Studios, who had commissioned the film score. The premiere was given by John Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra and Choir, with soprano Margaret Ritchie, on 14 January 1953; performances in London, Chicago, and Sydney followed soon thereafter. The initial reviews, all extremely favorable, dovetailed in making much the same points: comparison to Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony as a programmatic yet truly symphonic depiction of nature; a breaking of new stylistic ground by an octogenarian composer at the height of his creative powers, whose creativity continued to evolve; the work’s unconventional structure; the extremely colorful orchestration, with use of organ, vibraphone, and wind machine; and the virtuoso execution by the performers.

By contrast, the Symphony No. 8, composed in 1953–55 and premiered on 2 May 1956 by the same conductor and orchestra and dedicated to the former (“For Glorious John”), although received enthusiastically by its first audiences, provoked widely divided reactions from critics. Whereas RVW’s first seven symphonies were all considered to have explicit or implicit programs, for the first time he was seen to be offering a purely abstract work in that genre. Somewhat provocatively, he described the first movements as “seven variations in search of a theme” and said that the work utilized “a large supply of extra percussion, including all the 'phones and 'spiels known to the composer.” The negative notices duly seized upon these details to fault the work for deficit of form, dearth of inspiration, and reliance upon gimmickry.

Writing in The Manchester Guardian (May 3), Colin Mason charged that “the new symphony does not quite satisfy as a complete musical form.” While offering guarded praise for the first three movements, he excoriated the finale: “[T]he clattering din of the last movement, in which the whole percussion array is in action almost throughout, has no justification as a resolution of what has gone before, nor any in relation to the real musical content of the movement itself, which would have been more satisfying without this added noise, the only effect of which is to draw attention to the flimsiness and poverty of the material. This is the weakest movement in the symphony, at the bottom of the decline the work describes in its progress from first movement to last, a slight decline through the first three movements and a very steep one in the last.” Writing in The Observer (May 6), Peter Heyworth patronizingly characterized the piece as “a relatively slight affair. But just because it is so unpretending, it leaves in the main a pleasing impression,” and then damned not only the finale but the composer’s competence: “In the finale … he unlooses an orchestral tornado which sweeps up every hitting instrument within reach…. But this orgy is as unaccomplished as it is inappropriate. The trouble is that in matters of orchestral virtuosity Dr. Vaughan Williams remains an invincible amateur…. [I]t was just as well that Ravel was not present at the Free Trade Hall to hear what his old pupil was up to.” By contrast, Felix Aprahamian in The Times (May 6) declared: “From first to last, every bar of this admirably transparent score bears the hall-mark "R.V.W." This eighth symphony may well become the most loved and popular of the series.” Also in The Times (May 15), Frank Howes found that the summary statement of the finale’s chief themes “carries the argument to a satisfactory conclusion” and that a repeat hearing “removed some doubts” about the first movement as well.

In these two symphonies only, Boult’s recordings were not disc premieres, as the world premiere performers waxed them a few months earlier for HMV and Pye Nixa, respectively. The broadcast of the world premiere performance of the Eighth also has been released. Soprano Margaret Ritchie appears in both versions of the Sinfonia antartica, with Boult’s rendition adding readings by Sir John Gielgud of the prefatory quotations to each movement, a practice adopted by only five of seventeen recordings of that work released to date.

JAMES ALTENA

Although Boult had catholic tastes in repertoire, and was a doughty champion of 20th-century music during his tenure as head of the BBC Symphony, record companies (primarily HMV, EMI, Decca, Pye Nixa, and Lyrita) largely confined him to British repertoire, above all Elgar and Vaughan Williams. (Interestingly, though, the next most prominent name in Boult’s discography is Tchaikovsky!) In the years following his 1952–54 series of RVW’s first seven symphonies, with Nos. 8 and 9 following in 1956 and 1958, Boult recorded a number of mostly shorter works by that composer, most of which are presented here. TheFantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis,Fantasia on Greensleeves, English Folk Song Suite, and Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 were recorded for Pye Nixa (under the pseudonym “Philharmonic Promenade Orchestra” for contractual reasons) in 1953, and Old King Cole, Job, The Wasps, and The Partita for Double String Orchestra (the last-named in stereo) for Decca in 1953–56.

Boult recorded the Tallis Fantasia five times in the studio; a live performance from 1972 also has been issued. Strikingly, his interpretation of the piece changed markedly between his two monaural recordings (BBC 1940 and London Philharmonic 1953) and his three stereo versions (Vienna State Opera Orchestra 1959, London Philharmonic 1969 and 1975) and live account (New Philharmonia 1972). In the former two the performance is brisk, coming in at slightly over 14 minutes; in the latter four, it expands to slightly over 16 minutes. More strikingly yet, whereas the 1940 BBC version, despite more antiquated sound, matches the four later recordings for lushness of string texture, the 1953 account heard here radically shifts the emphasis to rhythmic incisiveness and clarity of the interweaving lines. It thus represents a unique take by Boult on the work, that more than justifies its restoration to the active catalog.

Job was another favorite RVW score of Boult’s—indeed, the score is dedicated to him. He recorded it in the studio four times (BBC SO 1946, London Philharmonic 1954 and 1958, and London Symphony 1970), plus a live performance with the London Philharmonic filmed in 1972 and available on DVD. Of these, the 1946 version suffers both outdated sonics and a degree of metrical stiffness, while the 1958 Everest recording is too closely miked and rather harsh sounding. The remaining three are all excellent; while this 1954 version (like the live 1972 outing) is less hard-driving than the 1970 account, it has no lack of energy or nobility and makes a great effect even today.

By contrast, this 1953 recording of the 1923 folk dance ballet Old King Cole is not only the only recording of the work by Boult; it apparently remains one of only three recordings ever made (the other two being by Richard Hickox for EMI, and an acoustical set led by the composer in 1925).

The Fantasia on Greensleeves (drawn from the 1928 opera Sir John in Love) and 1923 English Folk Song Suite were recorded in tandem by Boult three times, with the London Philharmonic in 1953, the Vienna State Opera Orchestra in 1959, and the London Symphony in 1970. All three sets are delightful and more or less on a par.

The Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 is, after the Tallis Fantasia, far and away the most often recorded work of RVW among the items included in this present set. Originally written in 1905–06 and revised in 1914, it is generally considered to be RVW’s first orchestral piece to speak in his distinctive voice. Boult would re-record it with the New Philharmonia in 1968; this earlier 1953 version is more extroverted in mood.

The Partita for Double String Orchestra from 1948, reworked from the earlier unsatisfactory version of a double trio for string sextet, is another RVW rarity. Apart from Boult, who again recorded it twice (the second time with the London Philharmonic in 1975), apparently only four other conductors—John Farrer, Vernon Handley, Ross Pople, and Bryden Thompson—have set it down on disc. As with the Tallis Fantasia, Boult significantly changed his interpretation of the Partita between his two versions; this earlier 1956 version has a far more ponderous opening movement and thicker instrumental textures throughout, but a brisker, more febrile finale than in the EMI remake.

Boult also recorded the delightful incidental music for Aristophanes’s The Wasps from 1909 twice, the second time with the London Philharmonic in 1968; he also recorded just the overture for Everest in 1958 and the march for Lyrita in 1973. If the latter version has more vivid recorded sound, the earlier one from 1953–54 has a more energetic snap to it.

JAMES ALTENA

The Sixth and the Ninth Symphonies of Vaughan Williams make apt discmates. Both share the same home key of E Minor, and open in dark, dramatic conflict but close in quiet, unresolved mystery. (Regarding the finale to the Sixth, RVW quoted the famous lines from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”) Both also exemplify the exploration of new instrumental colors and more dissonant harmonies that became signatures of the composer’s late period compositions.

The Symphony No. 6 was composed in 1944–47 and premiered on 21 April 1948 by Adrian Boult and the BBC Symphony. Initial reviews were uniformly laudatory, if somewhat patrician in tone, as illustrated by Ernest Newman’s notice in the Sunday Times on 25 April 1948: “Whether Vaughan Williams's new symphony … will soon achieve the popularity of some of its predecessors I cannot say;… but it is clear already that here we have a new Vaughan Williams, and a Vaughan Williams at the height of his powers. Superficially it links up in mood now with the vehement Fourth, now with the mysticism of certain others of his works. But it would be a mistake to regard the No. 6 as merely a re-travelling, even a superior re-travelling, of the old routes. It reveals a new order of ideas and a new logic in the handling of them. It is the work of a mind at once sensitive and powerful that at long last has succeeded in bringing its whole kingdom of thought and emotion under unified control; and in the light of it we shall now be able to listen to the composer's older works in a new way.”

Just as the Fourth Symphony was for some time seen as a harbinger of the violence that overtook Europe in the 1930s and 1940s with fascism and war, the Sixth was likewise initially viewed as a “war” symphony. While such interpretations fiercely annoyed RVW, in the case of the Sixth it fitted the public mood, and the work was embraced enthusiastically. The first two recordings of it were made almost simultaneously, by Leopold Stokowski and the New York Philharmonic on 21 February 1949, and by Boult with the London Symphony on 23–24 February. In 1950 RVW significantly revised the scherzo movement; Boult promptly recorded the new version, which displaced the previous one in 78rpm and LP releases, though CD releases have featured both.

The Ninth Symphony, composed in 1956–57, was premiered by Malcolm Sargent and the Royal Philharmonic on 2 April 1958 (the broadcast of that performance was previously released on PASC234). As with the Eighth Symphony, it left most critics nonplussed; Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times was virtually alone in hailing it “a masterpiece.” In the Manchester Guardian on 3 April, Colin Mason sniffed, “The key is E minor, the same as that of the sixth, and the composer has followed the precedent he set with that work of introducing his symphonies with a facetious analytical programme note of his own, in which he tilts at the professional analysers of musical forms…. Other strange notions nod in this composer's head. There is a march theme in the slow movement described by him as ‘barbaric.’ Later in the movement there is a ‘menacing’ stroke on the gong, introducing a ‘sinister’ recapitulation of an earlier theme…. The gong stroke makes no effect at all, and the supposedly barbaric march theme, in the pseudo-Chinese vein of the Eighth Symphony, is the silliest and poorest music in the work.” Three days later in the same publication, Adam Bell, while more positive in overall tone, observed: “[T]o complain that Vaughan Williams's Ninth lacks a coherent and consistent programme is really another way of saying that it does not quite convince as a piece of music. As a composer Vaughan Williams has always appeared to work best in response to the stimulus of an idea which, in musical terms, may be called philosophic; his most satisfying symphonies – 4, 5 and, perhaps, 6 – are all undeniably ‘about’ something. The new work does not seem (after two hearings) to have been written under the same pressure of experience.” As is now known, the Ninth originally did have a programmatic basis, in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, with draft references to Stonehenge, Salisbury Plain, Wessex, and Tess herself, all deleted before the score was finished. While the Eighth unjustly still languishes as RVW’s least often performed symphony, in recent decades the Ninth has won increased understanding and popularity, as a fitting capstone to the composer’s compositional career.

JAMES ALTENA

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies, Volume 1

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS A Sea Symphony

(Symphony No. 1)

1st mvt. - A Song for All Seas, All Ships

1. (1) Behold, the sea itself (3:28)

2. (2) Today a rude brief recitative (5:04)

3. (3) Flaunt out, O sea, your separate flags of nations! (3:02)

4. (4) Token of all brave captains (4:14)

5. (5) A pennant universal (3:42)

2nd mvt. - On the Beach at Night, Alone

6. (1) On the Beach at Night, Alone (3:53)

7. (2) A vast similitude interlocks all (7:49)

8. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo - The Waves (7:16)

4th mvt. - The Explorers

9. (1) O vast Rondure, swimming in Space (4:12)

10. (2) Down from the gardens of Asia descending (7:30)

11. (3) O we can wait no longer (5:14)

12. (4) O thou transcendent (3:26)

13. (5) Greater than stars or suns (1:25)

14. (6) Sail forth (2:34)

15. (7) O my brave Soul! (4:31)

Isobel Baillie, soprano

John Cameron, baritone

London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra

choir directed by Frederick Jackson

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

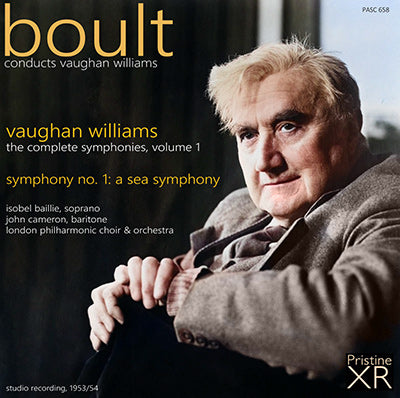

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Recorded 28-30 December 1953 & 1 January 1954, Kingsway Hall, London

Total duration: 67:20

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies, Volume 2

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS A London Symphony (Symphony No. 2)

1. 1st mvt. - Lento - Allegro resoluto (13:20)

2. 2nd mvt. - Lento (11:04)

3. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo (Nocturne) (7:03)

4. 4th mvt. - Finale. Andante con moto - Maestoso alla marcia - Lento - Epilogue (12:33)

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Pastoral Symphony (Symphony No. 3)

5. 1st mvt. - Molto moderato (9:43)

6. 2nd mvt. - Lento moderato (8:19)

7. 3rd mvt. - Moderato pesante (6:22)

8. 4th mvt. - Lento (10:53)

Margaret Ritchie, soprano

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

A London Symphony

Recorded 8 & 10 January 1952

Kingsway Hall, London

Pastoral Symphony

Recorded 12-13 December 1952

Kingsway Hall, London

Total duration: 79:17

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies, Volume 3

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No.4 in F minor

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro (9:10)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante moderato (10:10)

3. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo. Allegro molto (5:44)

4. 4th mvt. - Finale con epilogo fugato. Allegro molto (9:31)

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No.5 in D major

5. 1st mvt. - Preludio. Moderato (11:01)

6. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo. Presto (4:58)

7. 3rd mvt. - Romanza. Lento (10:58)

8. 4th mvt. - Passacaglia. Moderato (10:23)

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Recorded 2, 3 & 5 December 1953, Kingsway Hall, London

Produced by John Culshaw & James Walker

Engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson

Recordings supervised by the composer

Total duration: 71:55

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies Volume 4

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Sinfonia antartica (Symphony No. 7)

1. 1st mvt. - Prelude: Andante maestoso (10:53)

2. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo: Moderato (5:50)

3. 3rd mvt. - Landscape: Lento (11:26)

4. 4th mvt. - Intermezzo: Andante sostenuto (6:22)

5. 5th mvt. - Epilogue: Alla marcia, moderato ma non troppo (10:59)

Margaret Ritchie, soprano

John Gielgud, speaker

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No.8 in D major

6. 1st mvt. - Fantasia: Variazioni senza tema (11:07)

7. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo alla marcia (per stromenti a fiato) (3:55)

8. 3rd mvt. - Cavatina (per stromenti ad arco) (8:08)

9. 4th mvt. - Toccata (5:02)

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Sinfonia antartica (Ambient Stereo)

Produced by John Culshaw & James Walker

Recorded 10,11 December 1953

Recording supervised by the composer

Symphony No. 8 (stereo)

Produced by Christopher Whelan

Recorded 7-8 September 1956

Recorded at Kingsway Hall, London

Engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson

Total duration: 73:42

BOULT A Vaughan Williams Extravaganza

disc one (79:45)

1. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (15:00)

Recorded 12 & 14-15 September 1953, Walthamstow Assembly Hall

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Job - A Masque for Dancing

2. Scene 1: Introduction - Pastoral Dance - Satan's Appeal to God - Saraband of the Sons of God (9:55)

3. Scene 2: Satan's Dance of Triumph (3:43)

4. Scene 3: Minuet of the Sons of Job and Their Wives (4:15)

5. Scene 4: Job's Dream - Dance of Plague, Pestilence, Famine and Battle (4:28)

6. Scene 5: Dance of the Three Messengers (4:56)

7. Scene 6: Dance of Job's Comforters - Job's Curse - A Vision of Satan (4:47)

8. Scene 7: Elihu's Dance of Youth and Beauty - Pavane of the Sons of the Morning (5:27)

9. Scene 8: Galliard of the Sons of the Morning - Altar Dance and Heavenly Pavane (5:01)

10. Scene 9: Epilogue (3:08)

Recorded 9 & 11-13 January 1954, Kingsway Hall, London

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Old King Cole - Ballet

11. Introduction (3:30)

12. Pipe Dance (2:48)

13. Bowl Dance (1:22)

14. Morris Jig: 'Go and 'list for a sailor' (1:24)

15. Folk Song: 'Bold Young Farmer' (2:11)

16. Folk Tune: 'The Jolly Thresherman' (1:34)

17. General Dance (6:16)

Recorded 29 September 1953, Walthamstow Assembly Hall

disc two (73:33)

1. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Fantasia on Greensleeves (5:02)

Recorded 12 & 14-15 September 1953, Walthamstow Assembly Hall

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS English Folk Song Suite

2. 1. March - 'Seventeen come Sunday' (3:24)

3. 2. Intermezzo - 'My Bonny Boy' (3:27)

4. 3. March - 'Folk Songs from Somerset' (3:44)

Recorded 12 & 14-15 September 1953, Walthamstow Assembly Hall

5. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 (10:39)

Recorded 12 & 14-15 September 1953, Walthamstow Assembly Hall

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Partita for Double String Orchestra*

6. 1st mvt. - Prelude (6:27)

7. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo Ostinato (4:26)

8. 3rd mvt. - Intermezzo (Homage to Henry Hall) (4:24)

9. 4th mvt. - Fantasia (6:22)

Recorded 12-13 November 1956, Kingsway Hall, London

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Wasps (Aristophanic Suite)

10. 1. Overture (10:04)

11. 2. Entr'acte (2:58)

12. 3. March past of the kitchen utensils (1:47)

13. 4. Entr'acte (4:32)

14. 5. Ballet and final Tableau (6:17)

Recorded 28-31 December 1953 & 1 January 1954, Kingsway Hall, London

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Special thanks to James Altena

All recordings presented in Ambient Stereo except *Stereo

Total duration: 2hr 33:22

BOULT Vaughan Williams Symphonies Volume 5

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No. 6 in E minor

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro (8:20)

2. 2nd mvt. - Moderato (10:18)

3. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo: Allegro vivace (6:59)

4. 4th mvt. - Epilogue: Moderato (13:19)

5. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Speech after the recording of Symphony No. 6 (1:19)

6. SIR ADRIAN BOULT Introduction to Symphony No. 9 (0:27)

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No. 9 in E minor

7. 1st mvt. - Moderato maestoso (9:17)

8. 2nd mvt. - Andante sostenuto (8:05)

9. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo: Allegro pesante (5:36)

10. 4th mvt. - Andante tranquillo (11:52)

London Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Vaughan Williams

Symphony No. 6 (Ambient Stereo)

Recorded Kingsway Hall, London, 2, 3, 5 & 30 December 1953

Engineered by Kenneth Wilkinson

Produced by John Culshaw and James Walker

Recording supervised by the composer

Symphony No. 9 (stereo)

Recorded Walthamstow Assembly Hall, 26-27 August 1958

Produced by John Carewe

Total duration: 75:32