This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

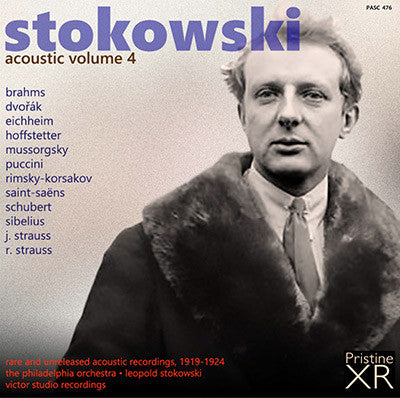

- Cover Art

Final instalment completing all of Stokowski's extant Philadelphia Acoustic recordings

"All

good things must come to an end and that’s the case with this series.

It’s been well compiled and transferred and has provided invaluable

première recordings of rare material. Who could want for more?" -

MusicWeb International

This fourth and final volume completes our set of Stokowski's complete surviving acoustic recordings, and again I'm grateful to Edward Johnson, Mark Obert-Thorn and Ward Marston for their assistance in sourcing these often rare and, again here in three cases, previously unissued recordings. The use of new pitch stabilisation techniques, along with careful re-equalisation and noise reduction, has once again made great strides in bringing us closer to the sound of The Philadelphia Orchestra at the time of its earliest recordings, and despite the massive limitations of the acoustic horn recording process, this is a delightful listen from start to finish.

One final bonus: Henry Eichheim's Chinese Rhapsody, never previously issued in the 93 years since it was recorded, appears here to be a world première release.

Andrew Rose

Johann STRAUSS II (1825-1899)

1. On the Beautiful Blue Danube (An der schönen, blauen Donau, arr. Stokowski), Op. 314 [4:35]

Recorded May 10, 1919

Victor 74627, matrix: C-22825-4

Antonin DVOŘÁK (1841-1904)

2. Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 "From the New World" - 2nd mvt - largo [4:39]

Recorded May 21, 1920

Victor 74631, matrix: C-24128-4

Nikolai RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908)

3. Scheherazade, Op. 35 - Young Prince and Young Princess [3:45]

Recorded March 25, 1921

Victor 74691, matrix: C-24629-10

4. Scheherazade, Op. 35 - Festival at Baghdad [4:14]

Recorded May 9, 1919

Victor 74593, matrix: Victor C-22810-4

Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

5. Samson et Dalila, Op. 47: Act 3 - Bacchanale [4:16]

Recorded December 6, 1920

Victor 74671, matrix: C-24630-5

Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

6. Finlandia, Op. 26 [3:52]

Recorded April 18, 1921

Victor 74698, matrix: C-24988-4

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

7. Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G minor transc. Stokowski [3:37]

Recorded May 21, 1920

Victor 1113, matrix: B-24130-3

8. Symphony No. 3 in F, Op. 90, 3rd mvt. - Poco allegretto [4:16]

Recorded April 18, 1921

Victor 74722, matrix: C-24125-8

Richard STRAUSS (1864-1949)

9. Salome, Op. 54 - Dance of the Seven Veils [7:32]

Recorded December 5, 1921

Victor 74729, 74730, matrices: C-25788-3, C-25789-2

Franz SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

10. Moment Musical No. 3 in F minor, D.780 transc. Stokowski [2:18]

Recorded January 28, 1922

Victor 66098, matrix: B-25941-6

11. German Dances, D.783 [4:42]

Recorded December 4, 1922

Victor 74814, matrix: C-27012-7

Modest MUSSORGSKY (1839-1881)

12. Khovanshchina - Entr'acte [3:54]

Recorded December 12, 1922

Victor 74803, matrix: C-27069-4

HENRY EICHHEIM (1870-1942)

*13. Oriental Impressions - 5. Chinese Rhapsody (arr. Stokowski) [5:49]

Recorded May 1, 1923

Unissued, Matrix Nos. B-27909-1/B-27910-1

Giacomo PUCCINI (1858-1921)

*14. Madama Butterfly - Act II: Prelude (Waiting music) [3:02]

Recorded 22 December, 1924

Unissued, Matrix No. B-31398-1 or 2

Romanus HOFFSTETTER (attrib. Haydn, arr. Stokowski)

*15. Quartet in F, Op. 3, No. 5 2nd mvt. - Andante Cantabile arr. Stokowski [3:03]

Recorded December 31, 1924

Unissued, Matrix No. B-31624-1 or 2

Recorded at Camden Church Studio (Victor Building no 22), Camden NJ, USA

*Previously unissued

Leopold Stokowski, conductor

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Reviews: MusicWeb International & Fanfare

The Blue Danube is truncated to four-and-half-minutes what remains is still very appealing and well recorded for the date, May 1919

This release is the fourth and final installment of Pristine’s series devoted to acoustic recordings made by Leopold Stokowski and members of the Philadelphia Orchestra. In reviewing Volume 3 for 40:2, I expressed some doubts regarding the value of acoustic orchestral recordings, since this primitive recording process was not capable of recording a full orchestra and had to make do with a few members of the orchestra clustered around a recording horn. Those reservations were only partially assuaged by the earlier disc, although I had no doubt that Pristine’s remasterings were probably better in sound than earlier efforts to resuscitate these recordings. That release did contain one item of great historical importance, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s 1924 recording of his own Concerto No. 2. As was the case with Volume 3, the selections on this release vary in sound quality and in the value of the performances, but there is nothing that matches the Rachmaninoff in significance. As before, a notable feature of Pristine’s restorations is freedom from the wow and flutter that one expects in material of this vintage. Even Pristine’s skilled ministrations, however, cannot change the fundamental character of these early recordings, and it should be immediately clear to the listener that they are acoustics, not electrical recordings. Most of the works on the new release are substantially abbreviated in order to fit onto one or two 78-rpm sides.

The 1920 Dvořák recording gives us a little more than one-third of the Largo movement. Although dynamic and frequency range are predictably limited, the sound is smooth and pleasing, and as full as one could hope. Instrumental details are clear. Stokowski recorded the complete “New World” with the Philadelphia in 1925, 1927, and 1934, with the All American Youth Orchestra in 1940, with “His” Symphony Orchestra in 1947, and finally with the New Philharmonia Orchestra in 1973. The 1920 excerpt is similar to the 1934 recording in its choice of tempo and relative steadiness of tempo, although there is more of an acceleration in the minor-key central section in the earlier performance. The 1927 recording is both quicker and more elastic, while the 1940 and 1973 readings are considerably slower—truly glacial, in fact. (I don’t have the 1925 and 1947 recordings.) In Pristine’s restoration of the 1920 recording, one can appreciate the beauty of the playing and Stokowski’s expressive but unexaggerated shaping, only to be disappointed when the selection comes to an abrupt end.

The 1921 excerpt from the third movement of Scheherazade (“The Young Prince and the Young Princess”) gives us a bit less than half the movement. As it opens, it sounds like the sensuous main theme is being played by a solo violin rather than the full section. Otherwise, the treatment is straightforward, with only hints of portamento. When he recorded the complete work with the Philadelphians in 1934, Stokowski’s approach in this movement was a bit more mannered, with more extravagant expressive gestures and more pronounced portamento. The 1919 “Festival in Baghdad” provides only about a third of the movement, skipping the solo violin passages at the beginning and coming to an end well before the shipwreck. The performance is again straightforward and in this case comparatively uneventful. The corresponding passages of the 1934 recording are more exciting, due to stronger dynamic stresses and a more strongly projected rhythm. The limited dynamic range of the acoustic recording may be partially responsible for this contrast.

The 1921 recording of the Poco allegretto from Brahms’s Third Symphony, although less drastically cut than some of the other selections, is not very rewarding. The sound bears little resemblance to a full orchestra, and the performance seems prosaic. The gain in realism in Stokowski’s 1928 Philadelphia recording of the complete work (as reissued by Biddulph) is striking, and aside from issues of completeness and sound, the 1928 version is a better performance, with more expressive playing and more convincing shaping. The pacing is a bit quicker in the later recording, with elasticity that is more pronounced but not excessive. The choppy 1921 solo horn is outclassed by its later counterpart.

With a timing of 7:32, Salome’s “Dance of the Seven Veils,” also recorded in 1921, is much less truncated than many of the other selections on the disc, although the opening flourish is cut. As is true elsewhere in this collection, the recorded sound comes off best in more heavily scored passages, where the thinness of the ensemble is less evident. Stokowski’s rendition here is more urgent and purposeful than sensuous. In his 1959 recording for Everest, with the Stadium Symphony Orchestra (a pseudonym, I believe, of the New York Philharmonic), he employs a more flexible and dramatic approach.

We get about half of the “Bacchanale” from Samson et Dalila (recorded 1920) and a bit less than that of Finlandia (recorded 1921), but the performances are urgent and exciting, and the sound offers a more convincing image of a full orchestra than in some of the other selections. Stokowski performs his own transcription of the Schubert’s Moment musicale in F Minor (recorded 1922). The playing here seems rather slack compared to his 1927 Philadelphia remake, which has greater tension, although the tempos are not much different. Schubert’s German Dances, D 783 (recorded 1922), was originally a solo piano work, but the transcriber is not named. The complete work manages to fit 16 dances into an 11-minute span (in Alfred Brendel’s 1973 recording on Philips). Stokowski provides not quite five minutes, and the playing is once again surprisingly slack.

One would expect Stokowski to excel in the Blue Danube (recorded 1919), but in the roughly half of the piece he gives us his rendition strikes me as mainly brisk and efficient, without much shaping, and does not really capture the joyousness of the music. Perhaps he was constrained by the cumbersome recording process, although as with all of these recordings there were multiple takes in an effort to get it right. The eccentricity for which Stokowski was sometimes known makes its appearance in the Brahms Hungarian Dance (recorded 1920), where the main tempo, which is supposed to be Allegro molto, is outlandishly slow. It doesn’t work. Although Brahms himself orchestrated this piece, Stokowski performs his own transcription, presumably from the four-hand piano original. The Khovanshchina excerpt, labeled here as an Entr’acte, is actually the prelude to act IV, scene 2. As it is playing, the disgraced Prince Golitsyn is being hauled away to exile. Here, too, Stokowski’s tempo strikes me as too slow, although not to the same degree. At this rate, Golitsyn’s journey to Siberia will be a very lengthy one. In terms of sound quality, though, this recording is one of the better ones on the disc. This selection was recorded in 1922; Stokowski rerecorded the piece with the Philadelphians in 1927 at a virtually identical tempo.

The last three items on the disc, by Henry Eichheim, Puccini, and Roman Hoffstetter, have never before been released, and according to Pristine Stokowski’s 1923 effort is the only known recording of Eichheim’s Chinese Rhapsody, which is part of a suite entitled Oriental Impressions. Eichheim (1870–1942) was an American composer, conductor, and violinist who took an interest in the music of the Far East and included some elements of it in his compositions. This one sounds like it could be music for an early Hollywood film set in the Far East, and I don’t find it of much value. The recording appears to be incomplete, as it terminates abruptly. The 1924 excerpt from Madama Butterfly, identified as “Act II: Prelude (Waiting Music),” is actually the “Humming Chorus” that ends act II, scene 1 (without, of course, the humming). The Hoffstetter selection, also recorded in 1924, is a Stokowski arrangement of the familiar Andante cantabile from a string quartet once attributed to Joseph Haydn as his op. 3/5. Stokowski here maintains a firm and fairly brisk tempo, avoiding the daintiness and saccharinity with which some musicians of this era treated 18th-century music.

As is often the case with Pristine CD releases, there are some issues with the accompanying printed matter. There is a typo in “Festival at Baghdad” (the “l” in “Festival” is omitted). The insert states that previously unissued recordings are marked with an asterisk, but no items are so marked. One must go to the Pristine web site to discover that the Eichheim, Puccini, and Hoffstetter pieces are first releases. While the insert for Volume 3 indicated the year when each item was recorded, for this release such information is available only from the web site. A common problem with Pristine inserts is that the track numbers are very small and faint and difficult for my elderly eyes to make out.

There can be little doubt that Pristine has presented these ancient recordings in the best possible sound, and they offer some listening pleasure, but it is equally clear that their inherent limitations in sonic accuracy cannot be completely overcome. That fact, and the fact that most of the selections are heavily cut and some do not show Stokowski at his best, probably limits the appeal of this release to Stokowski completists and those with a strong interest in the history of recording. For those not completely committed but wishing to give it a try, I would recommend going for Volume 3, because of the truly historic Rachmaninoff performance.

Daniel Morrison

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:3 (Jan/Feb 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.

The fourth and final volume documenting Stokowski’s acoustic legacy with

the Philadelphia Orchestra delves back and forth between 1919 and 1924

and provides another raft of rare and stimulating music-making (reviews

of Volume 1 ~ Volume 2 ~ Volume 3).

Again, too, one mustn’t expect much by way of symphonic unity, if one

can put it thus. These are bleeding chunks, abridgements and the rare

intact piece, all products of the recording horn in the days when one

was grateful for what one could get. So whilst the Blue Danube is

truncated to four-and-half-minutes what remains is still very appealing

and well recorded for the date, May 1919. The Largo from the New World

serves to remind one that Stokowski recorded the whole work almost as

soon as electric recording appeared, in 1925 and – by one of those

now-familiar quirks (look at Albert Coates’ legacy, for instance, or

Henry Wood’s) - he was to do so again in 1927. These two readings are

preferable to the 1934 recording but the 1920 torso is revealing for the

bass reinforcements, the sensitive portamenti and the rather abrupt

cut-off.

Thaddeus Rich was a long-serving Philadelphia

concertmaster, assuming the role in 1906 and relinquishing it two

decades later. Inveterate violin collectors may know he left behind a

measly four solo 78rpm sides for Okeh, but one of them was of some

Fauré, so at least the A&R gurus at that small company showed some

taste. He takes the solo in one of the movements from Scheherazade.

Another eminent member of the orchestra was that elite player Marcel

Tabuteau whose oboe weaves its exotic and evocative spell in the Bacchanale from Samson and Dalila. Whilst Finlandia was subject to the usual cuts it is notable for being the first American recording of the piece but with the Allegretto

from Brahms’s Third Symphony, Stokowski went one better. This is the

first recording of any movement from a Brahms Symphony: April 1921 was

the date. Later, as we know, Stokowski was to set down the first

American cycle of the complete Brahms symphonies.

Recorded over a luxurious two sides Strauss’ Dance of the Seven Veils

offers plenty of opportunities for panache and colour. It’s known that

the Philadelphia’s complement in these sessions actually diminished over

time, so by 1922 the Schubert German Dances was played by an orchestra

lining up 7-4-3-3 with winds and including a saxophone and contrabassoon

to get doubling or eking out that all important bass line. The

performance of the Entr’acte from Khovanschina

actually features an audibly bigger band, and appropriately so, for this

outstanding reading shows Stokowski’s Russophile antenna quivering with

power.

The final three items are all first releases. Both the

Puccini and Hofstetter – then commonly attributed to Haydn – are very

welcome to the official discography but the standout piece is Henry

Eichheim’s Chinese Rhapsody from his Oriental Impressions.

Eichheim was a violinist and had been in the Boston Symphony from

1891-1912. The rich tapestry of the winds and the rather fearsome

percussive outburst easily transcend the technology and are heard

splendidly in this restoration. Collectors will know that in the 1930s

Stoky recorded the same composer’s Bali, which can be found in a fascinating Philadelphia Rarities disc on Cala.

All good things must come to an end and that’s the case with this

series. It’s been well compiled and transferred and has provided

invaluable première recordings of rare material. Who could want for

more?

Jonathan Woolf

MusicWeb International