This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

FIRST REVIEW

An indifferent performance of Parsifal easily leads to dark suspicions that most of what its many detractors have said of it may be true. Such a performance confirms that Gurnemanz is the prime bore of opera, that Parsifal is the prototype of Canon Farrar’s Eric, that the Grail scenes are a parody, in the worst possible taste, of the most sacred rite of the Catholic Church, and that the episode of Kundry's attempted seduction of Parsifal, in which she plays on his feelings for his mother, is disgusting. These criticisms can be found, expressed in very outspoken terms, in Runciman's book on the Wagner operas—though the author was a true-blood Wagnerian—and, more temperately, in Hanslick’s review of the first performance of the opera, printed in the recently published English edition of a selection of his criticisms, edited by Harry Pleasants. The performance Hanslick attended must have been, from all accounts, a fine one: but no doubt he would have remained unconvinced even if the cast had been composed of angels, not so much because of his innate dislike (by no means unfairly expressed) for all Wagner's operas after Tannhäuser , but because of the false notion, as he saw it, that “beneath it all lies an unfathomably profound, holy meaning, a philosophic and religious revelation.” He would, as others may, have regarded the “psychological diagram” by Wieland Wagner, printed on the envelope containing the fifth disc of the Decca recording, as typical of the Wagnerites of his time, whose detailed analyses explaining every action and every bar with deadly industry, consumed reams of paper and bemused the reader.

All this is past history: but the Bayreuth Festival performance of last year, when this recording was taken, made a profound impression even on those whose antipathy to the opera was strongest, and though it is a weakness, pointing to real defects, that an indifferent performance of this strange work may rank one with the unbelievers, I do not think one can attribute the compelling power of the work merely to a performance so fine, reverent, and dignified as that which it received at Bayreuth, and which has now been so faithfully and splendidly recorded.

The fact is that the opera deals, however tortuously, with faith and the absence of faith, goodness and evil, in more direct terms than Wagner had ever used before, and that if he could not rise to the height of the great argument, not having the religious nature of Bach, the attempt he made in Parsifal is certainly not to be regarded as theatrical and insincere but, coming from so richly sensuous a nature, as a noble effort to clothe the great theme, as he so often does, with music worthy of it.

Hanslick speaks of “the solemn dullness” of the Prelude to the First Act and finds in its themes “neither charm nor any particular faculty of characterisation,” whereas it has always seemed to me that the opening theme and the way it is orchestrated is one of the finest things in music, expressing both the mystery of God’s love for man and man's anguished sense of remorse at his unworthiness. A universal theme. The purpose of these introductory remarks is to ask the reader to give some serious and unprejudiced thought to Parsifal and not to credit Wagner with intentions he did not have. It will hardly be necessary to say that the most revealing writing on the subject can be found in Ernest Newman's Wagner Nights. He takes pains, in the chapter on Parsifal, to warn the spectator against the too common error of identifying Parsifal vaguely with Christ, a suggestion which angered Wagner. “The idea of making Christ a tenor!—Phew!” he said.

The Decca Parsifal, like the Columbia Meistersinger, is an amalgam of various performances with the best preserved from each. In comparison with the Columbia recording one notices the relative absence of stage noise, although it is only fair to say that there is far less audible action in Parsifal. In some wonderful way, perhaps by tape cutting, we are also spared, except on one or two occasions, the coughing that disturbed some of the quiet moments in Meistersinger, though we are conscious throughout that we are hearing a performance in the theatre.

In the Prelude to Act 1 the five (and four) silent beats before the brass come in with the successive entries of the Faith theme are danger-points for “chatter,” but none can be heard in this recording, and the high wind chords preceding the Dresden Amen are perfectly steady. The previous Decca recording of the Prelude (LX3036) did not wholly avoid these faults, and though beautifully played as a whole, Knappertsbusch surpasses that rendering in the one under review.

The string arpeggios, through which the theme of the Love Feast shines, are finely articulated and lovely in tone, the brass are both massive and magnificent, and the tempo both here, and almost all through the long course of the opera, seems to me absolutely right.

The first scene of Act I, the domain of the Grail, takes up four sides of the discs, and I do not think I could pay a higher tribute to this inspired performance, and above all to the Gurnemanz of Ludwig Weber, than to say that I was continually surprised to find that each of these sides had come to an end. The scene of the morning prayer silently offered by Gurnemanz and the squires is accompanied by brass on the stage, and by strings, with extraordinary beauty of tone, in the orchestra: and it is here, more than anywhere, that Wagner approaches the serene ideal of Palestrina’s writing, which he so much admired.

Weber’s power both to interest and move us shows in the feeling and colour he gives to his words, an excellent example of which comes early in this Act just before the entrance of Kundry. He sings about the healing of Amfortas: “ihm hilft nur eines, nur der Eine!” (“but one thing avails him, but the one man”) and the way he differentiates between eines and Eine is a measure of his artistry.

Martha Mödl gives a remarkably effective performance of the one character in the opera that can so easily seem theatrical and contrived. A suggestion was made that at Bayreuth last year the part should be sung by two different artists in the first two Acts and by a third—an actress, not a singer— in the last Act, so as to bring out more fully the contrasting facets of Kundry’s complex nature. Martha Mödl, however, makes any such procedure unnecessary. In the first Act her speech is constrained and devoid of beauty of tone, in the second Act she is at first a creature in unwilling thrall to Klingsor, wishing only the oblivion of sleep, and then, when she enters the magic garden with the thrilling cry, “Parsifal!” the singer puts, as into the Herzeleide following, all the beauty of tone she can command. In the last Act she has only two words to sing, and it is left to the music, on these discs, to describe, as it most movingly does, her repentance.

The theme expressing the sickness and weariness of Amfortas, one of the most poignant in the opera, comes to us with great beauty of tone ('cellos and bass clarinet) as he is borne in on his litter; and the oboe solo, painting the peace of the forest—a lovely page I had forgotten—is also recorded most faithfully.

George London has the full range, with ample power on the upper notes, for the part of Amfortas, and the slight roughness in his singing makes more poignant the moving accounts, in the two Grail scenes, of his suffering. I have written before of Weber's long narration in Act I and of his singing in the Good Friday music. Here we have this noble singing enhanced in its appeal by the actuality of stage performance, and it is, together with the orchestral playing under Knappertsbusch, certainly the most outstanding glory of the performance. Wolfgang Windgassen is a youthful and appealing Parsifal in the first Act and in the following Acts he manages to convey in his voice some of the change of character made by the attainment of wisdom. The Transformation music between the two Scenes of this Act, which reaches a much more resonant climax than in the earlier studio recording, leads us to the scene in the Hall of the Grail Castle which is the supreme test of any recording of the opera. It is, let me say at once, a complete success, and I found it almost unbearably moving. The chorus of knights is most virile and contrasts with the unearthly beauty of the boys' voices coming from the extreme height of the dome. Here, as in the voice of Titurel coming from the tomb, the perspective is excellent. After Amfortas’s great cry, “Ebarme dich . . .” and the boys' singing of the theme (another great inspiration): “Dutch Mitleid Wissend, der nine Tor” (“Through pity quickened, the guileless Fool”) the Grail is uncovered and the great hall darkens. Anyone who regards this scene as merely theatrically effective must be extraordinarily insensitive and incapable of seeing below the surface of things: and I hope I shall not be misunderstood if I say that more of the deep penance of Amfortas and of the great reverence with which the scene is treated would not be unwelcome in the Christian Church. The little scene between Parsifal and Gurnemanz at the close of the Act is most eloquently done, the voices in the dome exquisitely echoing the Dresden Amen.

The tempestuous Introduction to Act 2 comes out well (though, as elsewhere, soft drum-rolls are lost), and Herman Udhe is convincingly evil as Klingsor. (I hope, for the sake of her voice, a stand-in performed the blood-curdling shrieks uttered by Kundry!) The horns announcing the arrival of Parsifal are a bit muzzy in sound and there was, on my reproducer, a slight lack of brilliance in the orchestral part describing the battle between him and the knights. The Flower Garden scene, on the other hand, is very well recorded. The intonation of the singers is adequate, the antiphonal effects came off well, and the florid orchestral part can at least be heard. After Kundry’s entrance, a wonderful moment, it has always seemed to me that Wagner’s invention faltered, in spite of some beautiful passages, and there is no doubt that the scene is overlong. We get here (and again in the Good Friday scene) two abrupt tape cuts, and I could have wished for a more resounding orchestral climax as the castle sinks and the garden becomes a desert. Apart from a rather noisy surface on the first disc in the Third Act and a moment or two of coarse recording of Parsifal in the first scene and the Knights' Chorus in the second scene, this last Act is very good indeed. The highlight, for me, was the orchestral playing of the music accompanying the bathing of Parsifal’s feet by Kundry up to the point where she is baptised by Parsifal. The radiant music is even lovelier than that especially associated with Good Friday, and it has been recorded with amazing fidelity.

All concerned with this issue have done a magnificent piece of work, but my last word of praise must be for Hans Knappertsbusch whose superb musicianship and deep insight into the opera must have inspired the whole of the cast—in which there is not a weak member—and the orchestra to give of their best.

Alec Robertson, The Gramophone, March 1952

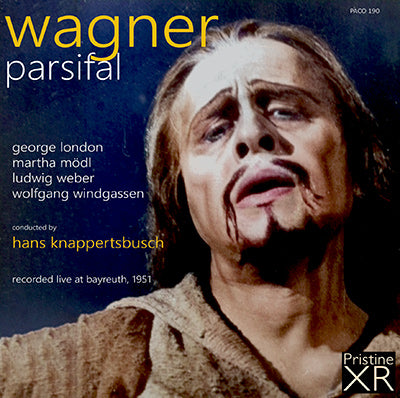

WAGNER Parsifal

disc one (54:49)

ACT ONE

1. Vorspiel (14:21)

2. He! Ho! Waldhüter ihr (5:51)

3. Seht dort, die wilde Reiterin! (3:06)

4. Recht so! - Habt Dank! - Ein wenig Rast (8:21)

5. He, du da! (6:27)

6. Das ist ein andres (5:04)

7. Titurel, der fromme Held (8:39)

8. Vor allem nun: der Speer kehr' uns zurück! (3:00)

disc two (61:32)

1. Weh! Weh! (1:39)

2. Du konntest morden, hier, im heil'gen Walde (4:04)

3. Wo bist du her? (3:20)

4. Den Vaterlosen gebar dir Mutter (3:11)

5. So recht! So nach des Grales Gnade (2:38)

6. Vom Bade kehrt der König heim (2:08)

7. Nun achte wohl, und lass mich seh'n (11:57)

8. Mein Sohn Amfortas, bist du am Amt? (2:41)

9. Nein! Lasst ihn unenthüllt (10:09)

10. Nehmet hin meinem Leib (17:09)

11. Was stehst du noch da? (2:35)

disc three (77:25)

ACT TWO

1. Vorspiel (2:17)

2. Die Zeit ist da (2:25)

3. Ehrwachst du? Ha!. (9:12)

4. Jetzt schon erklimmt er die Burg (4:16)

5. Hier war das Tosen (2:21)

6. Ihr schönen Kinder (2:15)

7. Komm, Komm! Holder Knabe! (5:32)

8. Parsifal! -- Weile (6:40)

9. Ich sah das Kind an seiner Mutter Brust (5:43)

10. Wehe! Wehe! Was tat ich? (5:14)

11. Amfortas! -- Die Wunde! (9:12)

12. Grausamer! Fühlst du im Herzen (6:45)

13. Auf Ewigkeit warst du verdammt (5:47)

14. Vergeh, unseliges Weib! (1:36)

15. Halt da! Dich bann' ich mit der rechten Wehr! (2:37)

ACT THREE

16. Vorspiel (5:33)

disc four (75:40)

ACT THREE continued

1. Von dorther kam das Stöhnen (4:28)

2. Du tolles Weib! Hast du kein Wort für mich? (3:15)

3. In düstern Waffenschmucke? (8:02)

4. Heil mir, dass ich dich wiederfinde! (4:12)

5. O Gnade! Höchstes Heil! (7:31)

6. Nicht so! -- Die heil'ge Quelle selbst (3:53)

7. Du wuschest mir die Füsse (6:35)

8. Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heut zu schön (10:04)

9. Mittag. -- Die Stund' ist da (5:43)

10. Geleiten wir im bergenden Schrein (4:33)

11. Ja, Wehe! Wehe! Weh' über mich! (8:11)

12. Nur eine Waffe taugt (9:13)

CAST

Amfortas - George London

Titurel - Arnold van Mill

Gurnemanz - Ludwig Weber

Parsifal - Wolfgang Windgassen

Klingsor - Hermann Uhde

Kundry - Martha Mödl

Altsolo - Ruth Siewert

Gralsritter - Walther Fritz

Gralsritter - Werner Faulhaber

Knappe - Hanna Ludwig

Knappe - Elfriede Wild

Knappe - Günther Baldauf

Knappe - Gerhard Stolze

Blume - Erika Zimmermann

Blume - Hanna Ludwig

Blume - Paula Brivkalne

Blume - Maria Lacorn

Blume - Lore Wissmann

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra & Chorus

conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Recorded live during performances at the Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, 30 July - 25 August 1951

Producer for Decca: John Culshaw, Sound Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Total duration: 4hr 29:23