This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

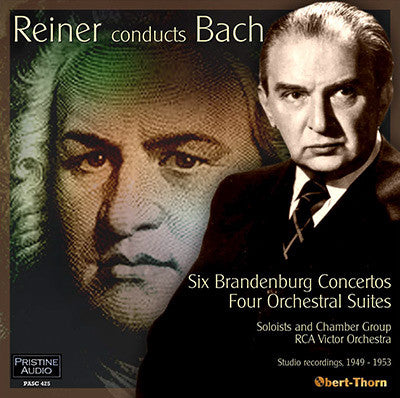

Fritz Reiner's brilliant Bach: The 6 Brandenburg Concertos and The 4 Orchestral Suites

"A virtuoso reading, incisive, with sparkle and rhythmic propulsion" - The Gramophone

A casual observer looking over Fritz Reiner’s pre-Chicago discography might well come to the conclusion that he was as much of a specialist in Bach as he was in the works of Richard Strauss, at least if measured by LP sides. Besides the three discs devoted to the Brandenburg Concertos and the two featuring the Orchestral Suites, Reiner had recorded an earlier version of the B minor suite in Pittsburgh, originally coupled on 78s with Lucien Cailliet’s transcription of the “Little” Fugue in G minor (forthcoming on Pristine). Yet, after becoming music director of the Chicago Symphony, he made only one further Bach recording, the F minor piano concerto with André Tchaikowsky, which was not released until years after Reiner’s death.

Nevertheless, as Philip Hart relates in his biography of the

conductor, “Reiner experimented restlessly with the Baroque.” From his

days in Dresden onward, he would include a harpsichord continuo in an

era when it was not yet fashionable. In his 1946 Pittsburgh Bach B

minor suite, “he added a lower octave to the bass to secure a more

‘symphonic’ nineteenth century sonority.” But in the recordings from a

few years later presented here, he strove for lighter textures. In

this, he was helped by the small forces employed for the Brandenburg

Concerto recordings (four violins, two violi, two celli, two basses,

with other personnel as needed) and by the spare acoustics of Columbia’s

30th Street Studio, which gave a close-up intimacy to the proceedings.

His soloists in the Brandenburgs included the cream of New York

instrumentalists. Violinist Hugo Kolberg had been Reiner’s

concertmaster in Pittsburgh; trumpeter William Vacchiano and violinist

William Lincer were playing in the Philharmonic, while oboist Robert

Bloom and flutist Julius Baker were at the time teaching and

freelancing. Landowska pupil Sylvia Marlowe was harpsichord soloist in

the Fifth Brandenburg and Fernando Valenti played continuo elsewhere.

The style, both here and in the later Orchestral Suite recordings, was what Hart called “a modified ‘authentic’ approach to Bach”, played with modern instruments but aiming at Baroque textures and tempi. This was a period of transition for Baroque performance in general, between the monumental Romantic approach heard in, for example, Stokowski’s Brandenburg Second (1929) and Furtwängler’s Brandenburg Third (1930) and the period instrument revival that would come to the fore in the 1960s. Seen in the context of their time, Reiner’s Bach recordings were on the progressive side of Baroque interpretation. Still, he could not resist allowing some string slides in the Third Suite’s famous Air; and the Second Suite, while perhaps lighter in texture than the earlier Pittsburgh version, is nonetheless markedly slower in tempo.

While Columbia kept the Brandenburgs in the catalog throughout the 1950s on three successive imprints (full-price Masterworks, then on their budget Entré and Harmony series), they have not seen an “official” reissue in over half a century. French RCA re-released the Suites on LP in the early 1980s, but not subsequently on CD. The present transfers were made from Harmony LPs for the Brandenburgs and the French pressings of the Suites.

Mark Obert-Thorn

Soloists and Chamber Group

Conductor: Fritz Reiner

Recorded in the Columbia 30th Street Studio, New York City

First issued on Columbia ML 4281 through 4283

• Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F, BWV 1046

Hugo Kolberg (solo violin); Weldon Wilbur (solo horn); Robert Bloom (solo oboe).

Recorded 28 October 1949.

• Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F, BWV 1047

William Vacchiano (trumpet); Felix Eyle (solo violin); Julius Baker (flute); Robert Bloom (oboe).

Recorded 2 December 1949.

• Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G, BWV 1048

Recorded 26 October 1949.

• Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G, BWV 1049

Hugo Kolberg (solo violin); Julius Baker, Ralph Eichar (Tracks 10 & 12) and Frederick Wilkins (Track 11) (flutes).

Recorded 21 October 1949.

• Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D, BWV 1050

Sylvia Marlowe (harpsichord); Hugo Kolberg (solo violin); Julius Baker (flute).

Recorded 3 November 1949.

• Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B flat, BWV 1051

William Lincer and Nicholas Biro (solo violins).

Recorded 27 October 1949.

BACH The Four Orchestral Suites

RCA Victor Orchestra

Conductor: Fritz Reiner

Recorded in Manhattan Center, New York City

First issued on RCA Victor LM-6012

• Orchestral Suite No. 1 in F, BWV 1066

Recorded 14 October 1952

• Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067

Julius Baker (flute)

Recorded 30 April 1953

• Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D, BWV 1068

Recorded 8 October 1952

• Orchestral Suite No. 4 in D, BWV 1069

Recorded 23 October 1952

Fanfare Review

Reiner’s Bach is awash in delicious orchestral colors and subtle nuances of phrasing

I first came in contact with Fritz Reiner’s Bach in 1979, when my Harvard roommate—Leonard Bernstein’s godson—showed up with one of the LPs of the 1949 Brandenburgs. Now we have the complete Brandenburgs plus the 1952–53 orchestral suites on CD, and I have to say they are an essential part of the Reiner discography. As Reiner was born in 1888, one might expect him to partake of the German Romantic tradition in Bach, perhaps best exemplified by Willem Mengelberg. Actually, Reiner’s Bach is unusually forward-looking for its period, especially the Brandenburgs. The one notable Romantic touch throughout all these recordings is a tendency to end movements with a sizable ritard. The absence of a Romantic outlook is not to say that Reiner’s Bach lacks warmth. In fact, these are some of the most emotional performances of the concertos and suites I’ve ever heard. Pablo Casals said that Bach should be played like Chopin, in other words, passionately. Reiner agreed. If you find this surprising from the stern-faced martinet who dominated orchestras, it’s well to recall that Reiner married three times and fathered a child out of wedlock. As with Sergei Rachmaninoff, an icy exterior masked a tinderbox of emotions. Reiner’s Bach is awash in delicious orchestral colors and subtle nuances of phrasing. He was in his 60s when he made these recordings, and they are the fruit of a lifelong search by a master conductor for the sound and meaning of Bach.

Reiner’s Brandenburgs are played by a small chamber group of strings joined by wind and brass soloists, plus a barely audible harpsichord continuo performed by the great Fernando Valenti. About another decade would pass before Max Goberman made the first recording of the Brandenburgs featuring one player per part (Pristine should consider reissuing the vast trove of great stereo recordings by Goberman). You might question why a titan of the orchestra like Reiner should consider directing these concertos with an ensemble that clearly could have performed them without a conductor. I think Reiner particularly enjoyed the challenge of taking a small group of instrumentalists and getting them to play with the maximum of expressivity. For example, we have his wonderful 1956 Chicago recording of Richard Strauss’s music for Le bourgeois gentilhomme, featuring less than 40 players. At the time of his death, Reiner was scheduled to record Mozart’s Serenade No. 10 for 13 winds. This was a type of music-making Reiner excelled at. My high school music teacher used to say there is nothing to conducting Bach; you just start and it goes. Reiner’s Bach, like Leopold Stokowski’s very different take on the composer, belongs to a wholly different level of sentiment. For instance, Oscar Levant in A Smattering of Ignorance writes of Reiner’s pursuit of the smallest audible string sounds, played with a bowing Levant calls “Reiner-paralysis.” It’s there in his Brandenburgs.

Reiner’s First Brandenburg is a majestic conception, with beautifully integrated, relaxed tempos. The Adagio is particularly flexible and searching, as emotional a miniature in its way as the Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana. In No. 2, trumpeter William Vacchiano, Gerard Schwarz’s teacher, makes a glorious sound. Reiner here weaves a tapestry of intricate rhythms and piquant colors. The first movement of No. 3 goes at a stately tempo, like a courtly dance. Reiner gets the maximum variation in dynamics from his strings. The last movement features a whirlwind of spiccato bowing from the violins. No. 4’s opening movement is wonderfully airy and bright, like a spring breeze. The string tone in the Andante is reminiscent of Vivaldi, whose Four Seasons only recently had been recorded for the first time. Reiner revels in the counterpoint of the concluding Presto. Sylvia Marlowe substitutes for Valenti in the Fifth Concerto, giving an exceptionally fluid performance in the first movement, including use of a lute stop, on a beautiful harpsichord. One wonders how much Reiner was involved in the slow movement, where the three soloists, heard by themselves, play with gorgeous ensemble. I’ve always felt that the last movement contains a quote of the aria “Bring Back My Acis,” from Handel’s opera Acis and Galatea. Reiner gets an exceptionally rich string sound in the last concerto. William Lincer and Nicholas Biro are listed as solo violinists, rather than violists, on the album cover, when in fact there are no violins in the piece. Lincer was principal viola of the New York Philharmonic, where he made a superb recording of Berlioz’s Harold in Italy with Leonard Bernstein.

The RCA Victor Orchestra in the orchestral suites is a fairly large ensemble, although not with as many strings as a full symphony orchestra. Reiner adopts slow, stately tempos for the introductory sections of the four overtures, but for the most part his speeds are fairly sprightly. Yehudi Menuhin said that the test of a performance of the suites is whether you feel like dancing to them. Reiner certainly meets this requirement. The Overture of the First Suite has a glorious, burnished sound, with a more audible harpsichord continuo than in the Brandenburgs. In the Forlane, Reiner secures an undulating feel like a flowing stream. Flutist Julius Baker is as much the star of the Second Suite as the conductor is. Reiner revels in the suite’s autumnal colors. He already had recorded it once, in Pittsburgh in 1946. The Sarabande evinces a depth of feeling drawn from the dance’s Renaissance roots. In the second Bourée, the harpsichordist sensitively uses the lute stop to accompany Baker. If you wish to explore the art of Julius Baker further, I would recommend his recording of Mozart’s Second Flute Concerto with Felix Prohaska. In the middle of the Third Suite’s Overture, Reiner employs a solo violin in place of the whole section, adding to the rhythmic verve. The continuo instrument changes to organ in the famous Air, helping, along with pizzicato basses, to make this an especially tender moment. Only the sailors of the H. M. S. Pinafore could have danced the concluding Gigue at the breathless tempo Reiner sets for it. The opening of the Fourth Suite’s Overture is especially slow, with a sonority reminiscent of a Renaissance wind band. Reiner’s tempo for the main section is jaunty, conjuring up visions of Fred Astaire. The second Bourée in Reiner’s treatment feels like the work of Lully or Marais. For the second Menuet, Reiner chooses one instrument per part, along with the harpsichord’s lute stop—decades before the Akademie fur Alte Musik, Berlin would make the first one instrument per part recording of all the suites.

Pristine has provided me with a mono release of these recordings, although there are downloads available in ambient stereo. Mark Obert-Thorn has secured agreeable sound throughout. I have one of the Harmony LPs Obert-Thorn used as source material for the Brandenburgs. The LP sounds crisp and bright. Obert-Thorn has gotten a somewhat warmer tone out of it than I would have expected, along with the excellent balance typical of Columbia’s 30th Street Studio in New York. The resonant, dark acoustic of the Manhattan Center contributes to the burnished sound quality of the suites. If you want these works on period instruments, I would recommend Philip Pickett in the concertos and Trevor Pinnock in the suites. Should you require stereo versions on modern instruments, my preference for the concertos is Alexander Titov directing Orchestra “Opera” on High Definition Classics. In the suites, I like Yehudi Menuhin. There is nothing quite like Reiner, though. Everything about his performances bespeaks a technical expertise and emotional connection rarely found in this music. These are interpretations to live with.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:5 (May/June 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.