This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

This release commemorates the 150th anniversary of the death of Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869) by presenting recordings by two of his greatest conductorial advocates: Sir Hamilton Harty and Pierre Monteux. Harty’s complete commercially-recorded Berlioz repertoire is collected here in its entirety for the first time (a 1991 Pearl CD featured all but the King Lear Overture), coupled with Monteux’s complete pre-war recordings of the composer’s works.

Irish composer/conductor Sir Hamilton Harty (1879 – 1941) considered Berlioz and Mozart as his two musical deities, due to what he perceived as their shared intuitive approach toward composition. His longest conductorial post was with the Hallé Orchestra of Manchester (1920 – 1933), whose founder, Charles Hallé, had been a friend of Berlioz. Hallé had begun a tradition of Berlioz performance with his ensemble which Harty continued and expanded into the then-new realm of recordings.

Beginning with acoustic versions of the Hungarian March from The Damnation of Faust (1920) and the Roman Carnival Overture (1924) for English Columbia, Harty presided over a string of nearly annual electrical sessions featuring Berlioz works. After leaving the Hallé, Harty made several recordings as a guest conductor of Beecham’s newly-formed LPO before making a final series for Decca in his last post as music director of the LSO, although the latter were hampered by the use of a small hall, inferior engineering and noisier pressings. Throughout, Harty’s immense vitality and disciplined ensemble playing have rightly made his Berlioz discs legendary.

For Pierre Monteux (1875 – 1964), an association with an orchestra steeped in the Berlioz tradition was also instrumental in developing his approach toward the composer. While still in his teens, Monteux became principal violist of the Colonne Orchestra, whose founder, Édouard Colonne, had known Berlioz and championed his works by presenting annual cycles. As Monteux’s former pupil and biographer, John Canarina, notes, “Monteux felt he gained great insight into Berlioz’s music through Colonne’s understanding of the composer’s scores.”

Although he conducted a wider array of Berlioz’s music, Monteux’s recorded repertoire of the composer was small, comprising besides the three works presented here only Romeo and Juliet and the Faust Hungarian March. While he went on to record the Symphonie Fantastique four more times after the 1930 Paris version, Canarina relates that Monteux considered this early effort his favorite, adding that “to this day, it is considered one of the greatest recorded performances of the work.”

The Harty transfers were made from the best portions of pre-war American Columbia and early laminated English Columbia pressings, while the Monteux recordings came entirely from US Victor “Z” pressings. Multiple copies of each record were located in order to ensure the best sources were used.

Mark Obert-Thorn

HARTY and MONTEUX conduct BERLIOZ

Symphonie Fantastique

Overtures, Marches and Orchestral Excerpts

Studio Recordings ∙ 1927 – 1935

CD 1 (68:51)

1. Beatrice and Benedict – Overture (7:45)

Recorded 2 November 1934 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

Matrix nos.: CAX 7331-2 & 7332-2 (Columbia LX 371)

2 Romeo’s Reverie and Fête of the Capulets (from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 17) (11:29)

Léon Goossens (solo oboe)

Recorded 5 September 1933 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

Matrix nos.: CA 13894-1, 13895-2, 13896-1 & 13897-2 (Columbia DB

1230/1)

3. Queen Mab Scherzo (from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 17) (7:26)

Recorded 2 May 1927 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix nos.: WRAX 2658-2 & 2659-1 (Columbia L 1989)

4. Dance of the Sylphs (from The Damnation of Faust, Op. 24)

(2:52)

Recorded 2 May 1927 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix no.: WRAX 2662-2 (Columbia L 2069)

5. Hungarian March (from The Damnation of Faust, Op. 24)

(3:51)

Recorded 2 May 1927 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix no.: WRAX 2663-2 (Columbia L 2069)

6. Royal Hunt and Storm (from Les Troyens) (9:45)

Recorded 10 April 1931 in Central Hall, Westminster, London

Matrix nos.: WAX 6062-1 & 6063-2 (Columbia DX 291)

7. The Corsair – Overture, Op. 21 (8:43)

Recorded 2 November 1934 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

Matrix nos.: CAX 7333-2 & 7334-1 (Columbia DX 664)

8.

Funeral March for the Last Scene of Hamlet (No. 3 from Tristia, Op. 18)

(8:02)

Recorded 18 April 1935 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

Matrix nos.: CAX 7525-1 & 7526-2 (Columbia LX 421)

9. Roman Carnival Overture, Op. 9 (8:58)

Recorded 12 February 1932 in Central Hall, Westminster, London

Matrix nos.: CAX 6277-2 & 6278-2 (Columbia LX 172)

London Philharmonic Orchestra (Tracks 1, 2, 7 & 8)

Hallé Orchestra (Tracks 3 – 6 & 9)

Sir Hamilton Harty (conductor)

CD 2 (79:33)

1. King Lear – Overture, Op. 4 (11:43)

Recorded 15/16 October 1935 in Thames Street Studio, London

Matrix nos.: TA 1985-II, 1986-III & 1987-III (Decca K 792/3)

2. Marche Troyenne (from Les Troyens) (4:00)

Recorded 16 October 1935 in Thames Street Studio, London

Matrix no.: TA 1988-II (Decca K 793)

London Symphony Orchestra

Sir Hamilton Harty (conductor)

3. Les Troyens – Prelude to Act 3 (4:09)

Recorded 31 January 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix no: CF 2830-1 (Disque Gramophone W 1142)

4. Benvenuto Cellini – Overture, Op. 23 (10:44)

Recorded 30 January 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix nos.: CF 2827-2, 2828-1 & 2829-2 (Disque Gramophone W 1141/2)

Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14

5. 1st Mvt.: Rêveries – Passions (13:04)

6. 2nd Mvt.: Un bal (5:56)

7. 3rd Mvt.: Scène aux champs (16:10)

8. 4th Mvt.: Marche au supplice (4:41)

9. 5th Mvt.: Songe d’une nuit de sabbat (9:07)

Recorded 20, 23 & 27 – 29 January and 3 February 1930 in the Salle

Pleyel, Paris

Matrix nos.: CF 2757-1, 2758-3, 2799-2, 2786-2, 2787-1, 2800-1, 2807-2,

2808-2, 2801-3A, 2806-2, 2816-2 & 2817-3A (Disque Gramophone W 1100/5)

Orchestre Symphonique de Paris

Pierre Monteux (conductor)

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Special thanks to Nathan Brown, Michael Gartz and Charles Niss for

providing source material

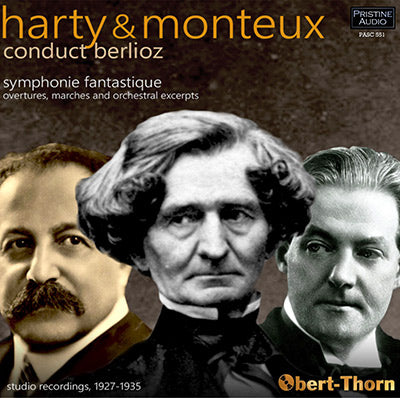

Cover artwork based on photographs of (L-R) Monteux, Berlioz & Harty

Total duration: 2hr 28:25

Fanfare magazine review

These are extremely old recordings, but the orchestral playing throughout is of an astonishingly high standard, and the recording quality is outstanding

Hamilton Harty was one of that very rare species, an instinctive Berlioz conductor—but that is an understatement. He had an exceptional understanding of this unique composer and produced terrific performances with all the essential Berlioz qualities, especially imagination. The electricity he generates in these recordings has rarely, if ever, been equaled. In terms of sheer exposure—performances and recordings—Colin Davis did more than anyone to establish Berlioz—not just the few popular overtures, of course, but the operas and other large-scale works—but he tended to normalize this eccentric music, moving towards moderation where fire and a sense of danger are essential. Munch’s performances of the overtures are generally more characterful than Davis’s, but still Harty is in a different class again. Immediately, with Beatrice and Benedict Overture, he is just perfect for this quicksilver piece—the prelude to an opera which Berlioz described as “a caprice written with the point of a needle.” Rather than wearing the concrete boots seemingly preferred by numerous other conductors of this piece, Harty has borrowed Mercury’s winged feet.

Many performances of Romeo’s Reverie (or, more accurately, Romeo seul … Tristesse … Concert et bal … ) suggest the young man is in a comatose state, but Harty’s pulsates with life, developing into passion, even in the Romeo seul section. Maybe the passion is not so necessary here, but it is infinitely preferable to the many faceless, bland, dreary versions committed to disc. As for the Fête of the Capulets—wow!—thrilling. This is so often flat-footed, but here—will the real Berlioz please stand up!—is a performance of magnificent drive, with flames leaping out in all directions. It’s incredible to hear an orchestra (London Philharmonic) from 80 or so years ago playing as though their lives depended upon it. What an inspiring conductor Harty must have been.

In the Damnation of Faust excerpts Harty is delightful and charming in the “Dance of the Sylphs,” but his “Hungarian March” is a little too fast (Berlioz’s marking of minim = 88 is usually ignored). Nevertheless, there is so much to admire here—the sheer vitality and panache, the spat-out grace-notes, the clear bass drum, the swagger, incisive brass, the swell up and down on the final chord—that the less than ideal tempo is easily overlooked. His acceleration may not be to everyone’s taste but it is undeniably stirring.

The Royal Hunt and Storm has atmosphere and, later, elemental power and demonic energy. Harty achieves superhuman playing—this time from the Hallé in 1931. The return of the slow music (Berlioz marks un poco ritenuto twice) relaxes maybe a little too much, but it is not indulgent. The beginning of The Corsair is brisk without any sacrifice in clarity. The following section—marked Adagio sostenuto—initially seems too slow, so that one feels an eighth note pulse rather than quarter, but Harty shapes it beautifully. However, on checking with the score, I find that Berlioz does actually mark an eighth note pulse (eighth note = 84), so this tempo turns out to be soundly judged. Subsequently, back in the swashbuckling music, he gets up a head of steam and one can feel the players on the edge of their seats.

How did Harty know of the Hamlet Funeral March back then? This impressive piece is very rarely played even today. Harty builds to a powerful climax and then a moving conclusion. To end Disc 1, Roman Carnival receives a rousing performance, then King Lear begins Disc 2. I have never come across this particular Harty recording, so bravo to Pristine. There is a devilishly good Beecham recording on BBC Legends, but Harty is even better. In the introduction he takes Berlioz’s marked tempo of Andante non troppo lento ma maestoso, avoiding the usual pomposity while also observing the staccato dots. His Allegro disparato ed agitato assai is dangerous in the best sense.

I have been a great fan of Hamilton Harty’s Berlioz (his Enigma Variations also is revelatory) for the past 40 years, so it is wonderful to see these performances reissued again. There could be no greater cause for celebration in this 150th anniversary year, though I hope I will be proved wrong in the coming months. I have already had one exceptional CD to review—François-Xavier Roth’s Harold in Italy and Nuits d’été, so who knows? There may be unsuspected Berliozians out there.

Monteux’s Benvenuto Cellini has plenty of energy, but also some over-deliberate passages, such as the Cardinal’s theme in the bass. Monteux made five recordings of the Symphonie fantastique, of which this is the first, but he was not generally regarded as an outstanding Berlioz conductor (some may disagree), in spite of being one of the few to record Romeo and Juliet many decades ago. The symphony is a problem piece (and, incidentally, among my least favorite Berlioz), accommodating both the Classical and the grotesque, with both characteristics essential. Monteux’s 1930 version has many strengths. It is never lethargic, avoiding the potential longeurs in the slow movement, and often intense and muscular—sometimes rather too emphatic. The contours are bold. There is no dreamy, pseudo-Impressionism. The “March to the Scaffold” has a steady tempo, nearer than most to what Berlioz, I believe, had in mind. Again, at a few points throughout the work, there is some walloping over-emphasis, but this is preferable to half-heartedness. Monteux evokes the necessary ferocity and can conjure up a devil of a storm. His finale is especially fiery and brimful of character. This is genuinely scary, larger than life—taken as seriously as it should be. Witches were much more present in peoples’ minds in those relatively superstitious times.

I realize that I have devoted much more space to Harty than to Monteux, but hopefully this is justified by his exceptional performances and his lower profile in terms of recording history. Finally, I must quote from Harty: “Berlioz and Mozart … are the two great intuitive composers as distinguished from the great logical ones.… And it is intuition that I count as the supreme thing in music. Call it heart against head if you will. In Berlioz, as in Mozart, you are always coming upon a beautiful, fresh-sprung melodic line such as no amount of head-work could have suggested. In Wagner, much as I love his music, I feel sometimes a mechanical process at work which makes me rate him below Berlioz.”

These are extremely old recordings, but the orchestral playing throughout is of an astonishingly high standard, and the recording quality is outstanding. Mark Obert-Thorn has worked his usual remastering magic.

Philip Borg-Wheeler