This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

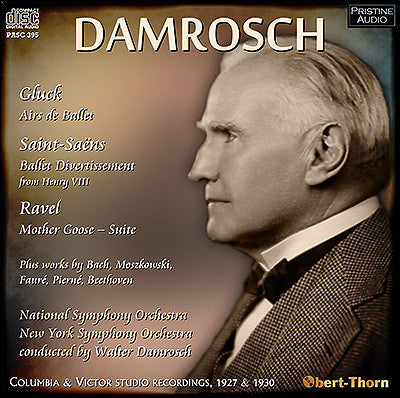

Walter Damrosch conducts Gluck, Saint-Saëns, Ravel and more

The great musical communicator in fine new transfers by Mark Obert-Thorn

For seven decades, Walter Damrosch (1862 – 1950) occupied a singular place in the American musical scene as conductor, composer and commentator. The son of conductor Leopold Damrosch, he emigrated from Germany with his family to America in 1871. Beginning his career at the age of 19, he returned to Germany for a period to study under Hans von Bülow, and became an assistant conductor for the fledgling Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1884. The following year, he led the first (non-staged) American performance of Parsifal only three years after its première, and succeeded his father as music director of the New York Symphony Orchestra.

It was with that ensemble that Damrosch began his recording career in 1903 for Columbia, setting down the first record made by an American orchestra under its own music director. He recorded only sporadically, returning to Columbia for another series with the NYSO in the 1920s. The selections here comprise his complete electrical recordings save for a 1928 Brahms Second Symphony. On them, we hear well-disciplined (for their time) ensembles, which use string portamento surprisingly sparingly. We also hear a conductor who can bring out both the colorful excitement of the Saint-Saëns and also the heartfelt tenderness of the Ravel (and sometimes both at once, as in the final movement of the Gluck).

The Beethoven lecture brings up another important aspect of Damrosch’s career, that of popularizer/explainer of Classical music to the masses. David Sarnoff appointed Damrosch to be the music director for NBC; (indeed, the National Symphony Orchestra which performs here is not the ensemble created in 1931 in Washington, DC, but rather the National Broadcasting Company’s house orchestra, a forerunner of the NBC Symphony). From 1928 to 1942, Damrosch hosted the Music Appreciation Hour radio program, broadcast weekdays for use in school classrooms, through which a generation of students was exposed to Classical music. While the type of “analysis” Damrosch presented, which envisions the Eroica Funeral March as highly-detailed program music, may strike modern listeners as, at best, naïve, it provided a convenient entry point for neophytes.

The sources for the present transfers were pre-war Victor “Gold” label pressings for all of the National Symphony recordings except for the first two sides of the Saint-Saëns, which came from a late Orthophonic disc; American Columbia “Viva-Tonal” editions for the Beethoven talk, the Pierné and the last movement of the Ravel; and Columbia “Full-Range” label pressings for the remainder of the Ravel. The Bach and Moszkowski sides were apparently only issued in inferior-sounding dubbed editions.

Mark Obert-Thorn

GLUCK (arr. Gevaert): Airs de Ballet

- 1 - Air from Iphigenia in Aulis

- 2 - Slaves’ Dance from Iphigenia in Aulis

- 3 - Tambourin from Iphigenia in Aulis

- 4 - Gavotte from Armide

- 5 - Chaconne from Iphigenia in Aulis

Recorded 13 May 1930 in Liederkranz Hall, New York City

Matrix nos.: CVE 59788-1, 59789-3 and 59790-1

First issued on Victor 7321 and 7322

6 - BACH (arr. Leopold Damrosch): Gavotte in D (from Sonata No. 6 for Solo Cello)

Recorded 20 May 1930 in Liederkranz Hall, New York City

Matrix no.: CVE 59797-3R

First issued on Victor 7322

SAINT-SAËNS: Ballet Divertissement from Henry VIII

- 7 Introduction and Entrance of the Clans

- 8 Scotch Idyl

- 9 Dance of the Gypsy

- 10 Jig and Finale

Recorded 16 and 20 May 1930 in Liederkranz Hall, New York City

Matrix nos.: CVE 59793-2, 59794-2, 59795-1 and 59799-3

First issued on Victor 7292 and 7293

11 - FAURÉ: Pavane, Op. 50

Recorded 18 September 1930 in Liederkranz Hall, New York City

Matrix no.: CVE 63663-3

First issued on Victor 7323

12 - MOSZKOWSKI: Perpetual Motion (from Suite No. 1, Op. 39)

Recorded 20 May 1930 in Liederkranz Hall, New York City

Matrix no.: CVE 59798-2R

First issued on Victor 7323

13 - PIERNÉ: Entrance of the Little Fauns (from Cydalise et le Chêvre-Pied)

Recorded 9 June 1927 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98367-2

First issued on Columbia 67345-D in Set 74

RAVEL: Mother Goose – Suite

- 14 - Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty (1:57)

- 15 - Hop o’ My Thumb (4:55)

- 16 - Laideronette, Empress of the Pagodas (3:36)

- 17 - Conversations of Beauty and the Beast (4:07)

- 18 - The Fairy Garden (3:38)

Recorded 7 and 9 June 1927 in New York City

Matrix nos.: W 98363-2, 98364-3, 98365-2, 98366-3 and 98368-2

First issued on Columbia 67343-D through 67345-D in Set 74

19 - Funeral March from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 (Eroica) explained at the piano by Walter Damrosch

Recorded 8 February 1927 in New York City

Matrix nos.: W 98313-1 and 98314-3

First issued on Columbia 7122-M

National Symphony Orchestra (Tracks 1 – 12)

New York Symphony Orchestra (Tracks 13 – 18)

Walter Damrosch (conductor)

Producer and audio restoration engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Walter Damrosch

Total duration: 71:54

Fanfare Review

This is a beast that makes an impression. I love it.

A couple of issues ago I quoted extensively from “Geniuses, Goddesses, and People,” by Winthrop Sargeant, a former violinist in the New York Symphony Orchestra and, later, the New York Philharmonic. The book contains his tongue-in-cheek descriptions of Willem Mengelberg’s rehearsal technique. Having given him his say about Mengelberg, I may as well use the occasion of this review to give him his say about Walter Damrosch, who led the New York Symphony Orchestra until its 1928 demise. We begin in a Paris hotel suite where Sargeant, an aspiring composer who also played the violin and French horn, is about to audition for Damrosch, hoping for a position in the New York Symphony Orchestra: “I really needed the job and, in order to make the best possible impression, I decided to attack him on three fronts. I would play the violin for him. I would then play the horn, to show what a useful fellow I could be around a symphony orchestra; and then I would show him one of my compositions, to demonstrate, if not my talent, at least my general musicianship. To load the dice still further in my favor, I picked the César Franck Violin Sonata to play, knowing that he would accompany me and that it had a very difficult piano part which would probably keep his mind, to some extent, off my fiddle-playing. Damrosch greeted me with senatorial calm, sat down at the piano, didn’t even open the music to the sonata but proceeded to accompany me entirely from memory. He listened to my reasonably accurate tooting on the horn, gave a patrician nod and turned to my composition. It was a dreadful composition, showing little evidence of talent, and written in all the extreme dissonant idioms that were popular among “advanced” composers of the 1920s. The only impressive thing about it was its sheer complexity. It was scored for an oversize symphony orchestra, and its parts—from piccolo to double bass—were spread over a formidable conductor’s score some forty lines deep. It was, in fact, so complicated that I had been certain until that moment that even a conductor of Damrosch’s ability would scarcely be able to make head or tail of it without laboriously taking it apart and studying it line by line. I felt reassured because I knew there wouldn’t be time to do that, and I thought he might be superficially impressed by the mere quantity of notes it contained. Damrosch picked up the score, looked at it absently for a few minutes, and took it over to the piano. Then, to my amazement, he proceeded to play the whole thing as if it were a simple piece of piano music, getting all my abstruse and complex dissonances exactly right and even adding an interpretive flourish or two that gave the piece a sense of form and climax. It was a tremendous feat of musicianship. Later on I shall have something to say about Damrosch as a conductor. Owing to certain peculiar limitations he was not a great one. But among the great ones, I have never met one who had a more penetrating knowledge of the technical side of music....”

“Walter Damrosch belonged to an era in American musical life that is now extinct. Its protagonists were people like his father Leopold and the great Middle Western symphonic pioneer, Theodore Thomas. It was an era of rough-and-ready performances, when personality was more important than technique and when the sheer glamor of a hundred-man orchestra outweighed the finer details of its symphonic workmanship. A modern metropolitan audience would swoon at what we sometimes offered as performances. It was not unusual for a whole section to get lost in the middle of a composition, adroitly fake its way through a mass of musical confusion, and find itself again in time to bring down the symphonic curtain with a well-chosen final chord. This was particularly apt to happen in the case of unfamiliar and dissonant ‘modern music.’ Since the music was dissonant anyhow, a few extra impromptu dissonances didn’t seem to matter much. The audience, in any case, seldom noticed the discrepancies and undoubtedly attributed the strange sense of harmonic confusion to the progress of the technique of modern composition. Damrosch performed an enormous amount of ‘modern music’—first performances of new works by composers like Hindemith, Schoenberg, Honegger and Stravinsky….”

“Damrosch had two qualities which ideally suited him for this missionary work: an absolute imperturbability—if the theater blew up it could be confidently predicted that he would be found somewhere in the wreckage calmly waving his baton—and an uncanny ability to handle audiences. He would often stop the concert to make speeches—and in a senatorial, fatherly way he was an admirable speaker. Considered strictly as a conductor, he was a curious case. His knowledge of music was extraordinary. He knew more scores, and knew them better, than many a far more polished and technically adroit maestro. He was a composer of some distinction, and an excellent pianist. But in the peculiar art of conveying musical ideas by means of gesture—an art that constitutes the conductor’s most fundamental gift—he was without any trace of talent whatsoever. His baton would swing automatically—down, left, right, and up again—like the mechanical pendulum of a grandfather clock, indicating nothing whatever of the passion or excitement which he undoubtedly felt as a musician. The only thing that could be said for Damrosch’s “beat” was that it was perfectly clear. Even the New York Symphony found it difficult to get lost with that relentless, foursquare gesture patiently ticking off the measures of the music.”

In addition to its interesting contents, this CD has a sample of Damrosch’s ability as a lecturer, trying to bring the slow movement of Beethoven’s “Eroica” to life for an unseen (in this case) audience. I assume that the Gluck Airs de Ballet Suite is a concoction of his own, which works quite well with what sounds like a smallish orchestra. I am puzzled about the final dance, a chaconne that is supposedly from Iphigenia in Aulis. I suppose Gluck could have used it there but I associate it with the Orfeo ballet music. The Henry VIII dances are a divertissement that concludes the second act of Saint-Saëns’s opera. I’m surprised that it doesn’t get recorded more. Damrosch includes five of the seven dances. Jacques d’Amboise once made a very agreeable ballet called Irish Fantasy using this music—I wish the New York City Ballet would revive it sometime. The three short pieces by Fauré, Pierné, and Moszkowski would benefit from less “boxy” sound. The Moszkowski is an interesting discovery that should please any purchasers of this disc. The strangest and most intriguing performance on the CD is that of Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite. The use of a small-sized body of players and the fairly close miking don’t just give the performance an appropriate intimacy, they also expose hitherto seldom-noticed and fascinating details of orchestration that poke through the thin sonority. Damrosch leads the slowest Pavane and “Petit Poucet” I have ever heard and he’s in no hurry in “The Conversations of Beauty and the Beast.” Given a contrabassoon that almost snarls like a serpent (the instrument, not the reptile), this is a beast that makes an impression. I love it. Happily, Damrosch acknowledges the sentiment of the music and the sheer exposure of detail is a delight. You may draw your own conclusions about his “foursquare beat.” Incidentally, the “National Symphony Orchestra” is not the one in Washington that Hans Kindler founded but, rather, an ancestor of the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:4 (Mar/Apr 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.