This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

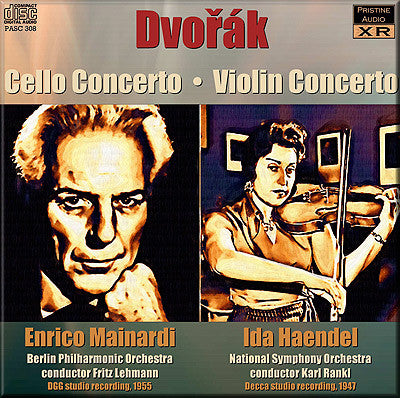

Superb 32-bit XR remasters of the Dvořák string concertos

Mainardi and Haendel on top form for these excellent studio recordings

I had two LP copies of the Mainardi to work from - the original DGG issue and the mid-60s Heliodor fake-stereo reissue. In terms of surface quality and fidelity the later pressing was infinitely preferable to the original, in near mint condition and with superb sound quality. I was able to strip out the Heliodor stereo processing and remove any phasing artefacts prior to 32-bit XR remastering, which proved highly successful in bringing further treble clarity to the recording.

From the LP the recording was pitched at A=451Hz. However, analysis of mains electrical hum suggested a true tuning of A=450Hz and this has been used for the final remastered version. Likewise the Decca Haendel 78s transferred at around A=451Hz but electrical hum indicated a performance pitch of A=445Hz, which is what is heard here.

Decca's ffrr 78s date from the final months of direct-to-disc recording, prior to tape, and here indicate just how successful this method had become by 1947. The sound is clear, the frequency range well-extended, and with XR remastering little hint remains of the shellac origins of the concerto, which stands up very well in comparison to the cello recording.

Andrew Rose

Recorded 24 January 1955

Jesus Christus-Kirche, Berlin

First issued as DGG 18236

Transfer from Heliodor LP 89 520

Enrico Mainardi cello

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Fritz Lehmann conductor

Recording producer: Victor Olaf

Recording Engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson

Recorded 30-31 July 1947

Kingsway Hall, London

First issued September 1948

Transfer from Decca 78s AK.1744-47

Matrix Nos: AR.11472-79

Takes 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2

Ida Haendel violin

The National Symphony Orchestra

Karl Rankl conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, September 2011

Cover artwork based on photographs of Enrico Mainardi and Ida Haendel

Pristine Audio is grateful to Al Schlachtmeyer for the generous donation of the Haendel discs

Total duration: 69:00

MusicWeb International Review

Her playing of the finale’s folk incidents, and associated crisp chording, is a pleasure to hear

These two concerto performances make contrasting claims on the listener.

Ida Haendel’s 1947 recording of the Violin Concerto was made in

Kingsway Hall, accompanied by the pick-up National Symphony Orchestra

under Karl Rankl. This was composed of first-rate musicians, but they

didn’t always form a first rate orchestra. There are moments of rhythmic

uncertainty, and a slight feeling of under-engagement from time to time

which, whilst hardly an impediment to the soloist, means that the

recording as a whole is slightly less impressive than it might have

been. Haendel’s tone is quite fervent, but it’s well controlled, and

never seems out of scale - albeit her vibrato has a tendency to seem a

touch fast on occasion. Her phrasing is eloquent, maybe a touch

unidiomatic at a few paragraphal points, but her playing of the finale’s

folk incidents, and associated crisp chording, is a pleasure to hear.

Dutton issued this recording well over a decade ago, as part of an

all-Haendel disc - the Tchaikovsky with Basil Cameron was the other main

work. The transfers represent the divergent aesthetics of these two

labels - a somewhat dampened treble from Dutton, a more expansive top to

bottom range from Pristine.

I know two of Mainardi’s other

performances of the Concerto. I’ve reviewed the live one with Jochum on

Tahra 638-39; then there’s the wartime inscription with van Kempen and

the Staatskapelle Berlin, on 78s. On neither of these occasions has he

ever much impressed. He always started with a sluggish, wan, almost

sullen first entry, and things progressed from there. It may chart some

kind of emotive development for him, but it rather flies in the face of

the composer’s express markings He never had an especially beautiful

tone but he was always a tactful player, even if he is raspily-toned

here in places and his downward scale is ponderous. In fact Lehmann and

the orchestra prove to be luxury casting - outstanding winds, commanding

bass line - and rather upstage the dogged soloist. It’s telling that

one listens to little rhythmic emphases from Lehmann and to the

contributions from the orchestra’s principals with as much interest as

one does to the soloist. I do admire Mainardi - just not in this work.

Coupling historical performances like this makes some sense, but to

saddle a good performance of the Violin Concerto with a rather

(soloistically) nondescript one of the companion work will cause

problems for potential purchasers.

Jonathan Woolf