This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Vaughan Williams' Sixth Symphony in E minor was premiered with Boult conducting in April 1948, and Boult's first recording of the piece followed in February of the following year, just three days after Stokowski had made the premiere recording. Boult was to return to the piece in the Decca studios in the early 1950's with the London Philharmonic - by this stage the Scherzo had been revised by the composer.

What we hear in this recording is the original Scherzo - HMV did also later issue an alternative disc with the revised Scherzo as part of this album.

It's interesting to look back to a review of the day - from The Record Guide (which gave it a star), written at a time when the work was still new and the composer had yet to complete his life's work:

"In the massive, brooding sadness of this extremely powerful work Vaughan Williams unites, as never before in his career, the two moods of his vision. It has the nature of a symphonic poem rather than of a symphony proper, and the four movements, although clearly divided, are played without a break. The Epilogue, which preserves an undeviating pianissimo for about twelve minutes, is an astounding imaginative feat. The muted orchestra weaves a cat's-cradle of glassy filaments through which shines a dead white light. It is like the final echo of a vanishing world - a human cry lost in the cold of interstellar space. The only other works which produce an impression at all similar are Sibelius's Tapiola and the Finale of Chopin's Sonata in B flat minor. The performance on the whole is admirably recorded, but the pianissimo in the Epilogue is not quite consistently preserved, and the woodwind solos at the end are distractingly near. In every other respect this is an issue worthy of a great work. (Since the Symphony was recorded the composer has revised the Scherzo in one or two places. The revision is very slight - indeed, scarcely noticeable; but the movement was re-recorded and the disc containing the new version is that now issued with the rest of the set.) "

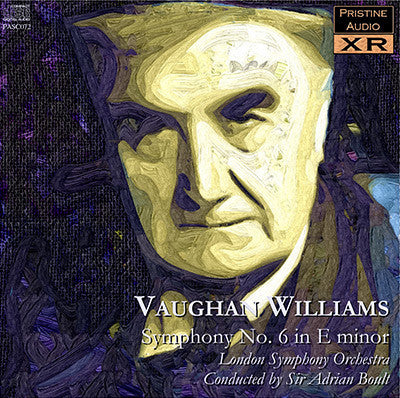

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Symphony No. 6 in E minor

Conducted by Sir Adrian Boult

Recorded at Abbey Road Studios, London, 23-24th February, 1949

Issued as HMV C.3873-6, Matrix numbers 2EA 13623-30.

All first takes except side one, take two.

Natural Sound remastering by Andrew Rose March 2007

Duration 32:54

Fanfare Review

Pristine’s re-mastering is simply phenomenal

Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Symphony in E Minor, written during and after World War II, is often considered to be one of the composer’s finest and most emotional works, capturing the horrors of war and the spirit of hope that arose during that conflict. My own feelings about the score may differ from yours, but I found much of the first movement harmonically and rhythmically interesting but bombastic in expression.

Fortunately, the music does not lie there, nor does it become repetitive or predictable. The development of mood seems to me as or more important than the actual musical structure, which in scoring and musical expression is very close to movie music. (Not that I have a problem with movie music per se, only that I believe such music is meant to accompany the visual images of the film and not to be listened to as an independent entity.) Like Richard Danielpour’s opera Margaret Garner, which I have seen and heard but which has not been recorded, the composer’s deep personal convictions and feelings often transcend music that in other hands would be derided as derivative or insincere. The still, quiet ending of the work, so different from its splashy beginnings, almost seems a resignation of man’s fate in the face of insuperable odds.

This symphony has several fine readings available on CD, among them Kees Bakels’s 1994 release on Naxos and Bernard Haitink’s with the London Philharmonic on Angel. I found Bakels to be more supple in rhythm than Boult, but less powerful, gripping, or sure of the dramatic impetus of the music. Haitink has the power and some of the feeling, but he conducts the work—particularly the opening section—with a far stiffer rhythm than even Boult. Thus, I would still have to recommend Boult for an overall concept of the work, though Bakels would make a fine digital alternative.

Adrian Boult has always been one of my conducting heroes, vastly underrated and for the most part underrecorded. I have long treasured his 1959 recording of the Mahler Symphony No. 1 for Everest, in which he was deputized at the last moment for an indisposed Jascha Horenstein, and of course his earlier recordings (mono in 1945, stereo in 1961) of Holst’s Planets are considered important historical readings. His very obvious commitment to this work is as sincere as the composer’s vision, which lifts it above the rather shallow yet spectacular recording made by Leopold Stokowski three days before this one, which was made on February 24, 1949. Yet I feel hesitant in recommending this disc without reservation because of my somewhat ambivalent view of the music, which might strike other listeners as less valid than I found it. I would rather suggest that an auditor new to this work sample it (the Scherzo, later slightly revised by the composer, is available online). As is the case with all of the recordings I’ve heard, Pristine’s re-mastering is simply phenomenal, bringing out clarity and warmth not previously noticeable in this historic performance.

Lynn René Bayley