This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

"The work and the interpreters are as happily met as one could wish" The Gramophone

Sir Hamilton Harty demonstrates why his Hallé was "the soundest orchestra in the country" in 1928!

The sources for the present transfers were primarily American Columbia pressings from the late 1920s through the late 1930s a “Royal Blue” shellac copy for the Smetana; a combination of a blue “microphone” label pressing and a laminated Australian Columbia for the Liszt; “Full-Range” era copies of the Brahms pieces and the Dvorak Slavonic Dance; a “Viva-Tonal” pressing of the Carnival Overture; and a c.1935 “large-label post-Viva” set for the New World Symphony, with two sides taken from a “Viva” copy.

The New World posed particular restoration problems in that it required not only significant pitch corrections throughout each side, but also volume level adjustments to counteract the frequent gain-riding of the original engineers. Once fixed, however, this early set rather surprisingly revealed the best recorded sound of any of the discs, with a level of detail and breadth of frequency range associated with recordings made a decade later.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

SMETANA The Bartered Bride - Overture [notes / score]

Recorded 17 November 1933 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 1

Matrix nos. CAX 6995-2 and 6996-1 • First issued on Columbia DX 562

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Sir Hamilton Harty conductor

-

LISZT (arr. Doppler) Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 [notes / score]

Recorded 10 April 1931 in the Central Hall, Westminster

Matrix nos. WAX 6060-3 and 6061-2 • First issued on Columbia LX 132

- BRAHMS (arr. Parlow) Hungarian Dance No. 5 [notes / score]

-

BRAHMS (arr. Parlow) Hungarian Dance No. 6 [notes / score]

Recorded 11 February 1929 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix nos. WA 8539-2 and 8540-1 • First issued on Columbia 5466

-

DVOŘÁK Carnival Overture [notes / score]

Recorded 30 April 1927 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix nos. WRAX 2556-1 and 2557-2 • First issued on Columbia L 2036

-

DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 (“From the New World”) [notes / score]

Recorded 2 May 1927 in Free Trade Hall, Manchester

Matrix nos WRAX 2671-2, 2672-1, 2673-1, 2674-1, 2675-2, 2676-1, 2677-2, 2678-2, 2679-2 and 2680-2

First issued on Columbia 9770 through 9774

Hallé Orchestra

Sir Hamilton Harty conductor

-

DVOŘÁK Slavonic Dance No. 1 in C major, Op. 46, No. 1 [notes / score]

Recorded 17 October 1933 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3

Matrix no.: CA 14066-1 • First issued on Columbia DB 1235

Myra Hess & Sir Hamilton Harty piano duet

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

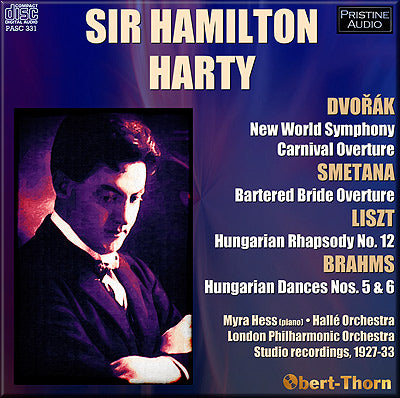

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Sir Hamilton Harty, c.1920

Special thanks to Nathan Brown and Charles Niss for providing source material

Total duration: 65:36

DVOŘÁK New World Symphony

The Dvorak is thus divided: first movement on one record ; second on three sides ; Scherzo on sides 6 and 7 ; Finale on last three sides. This re-recording is in the same hands as the original performance. The Hallé, in the opinion of most critics, is at present the soundest orchestra in the country, and though it would be possible to add even to it certain graces of style, there is no better example of cohesion, of the rich fruits of careful, consistent and long-continued work under a wise and balanced conductor, to be heard amongst us. The strings sometimes are a little rough (that is not a prominent quality in this performance, though), and the woodwind has not quite the polish of our best London men—Murchie, Goossens, H. Draper, for instance. The wind chorus is not easily to be beaten for well bound, round, sweet playing. I find the solo bits in the Largo somewhat loud. This movement might conceivably be made still more winsome. The strings never bite too much, and don't become shrill. There is room for plenty of personal preference as to how this work should be interpreted. For myself, I should have liked just a shade more of spaciousness for the tunes; but that isn't a grumble. Indeed, I have none to make. The work and the interpreters are as happily met as, knowing both intimately, one could wish.

K. K., The Gramophone, May 1928

Fanfare Review

Transfers that astound with their life and color

Hamilton Harty (Sir Hamilton to you Brits) lived from 1879 to 1941. He led Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra from 1920 to 1933 and the London Symphony from 1932 to 1935, after which his conducting career was cut short by illness. As a composer, he was best known for his arrangements of Handel’s Water Music and Royal Fireworks Music, which became the standard versions played throughout the world, until the period-practices movement consigned them to oblivion. Harty’s 1933 recording of the Overture to The Bartered Bride supports his reputation as a spirited interpreter, and the London Philharmonic plays impeccably. It is so fine, so absolutely right, that, sight unseen, I would have sworn it to be by a Czech orchestra and/or conductor.

The 12th Hungarian Rhapsody may be the most dreadful piece of so-called classical music I’ve ever been forced to listen to. Perversely, it receives the finest sound here; although the distortion of the strings is typical for its time, woodwinds and harp solos belie its 1931 date by half a century, with virtually no surface noise. The performances of the Brahms dances strike me as nothing special and have some mushy attacks. Harty’s Carnival Overture is unusually well-balanced, capturing its high spirits, as most performances do, but also relaxing appropriately for its tender moments, as few do. A lack of ambient reverberation enables us to hear a few details obscured by most modern recordings.

Paul Ingram waxed ecstatic over these Dvořák performances (on the Hallé Orchestra’s own label) in Fanfare 28:4, saying he would rather hear this 1927 “New World” than any later recording. I won’t go that far, but I understand his point: This is a well-played performance that avoids most extraneous effects, including some tempo changes that have become consensus. This leaves a first impression that the performance is too fast (33:41, with no exposition repeat), but on a second hearing, Harty seems eminently right. Having set the Allegro molto for the exposition, Dvořák wrote no tempo indications (according to my 1937 score). Harty errs only in speeding up for the final 29 measures of the coda. Unfortunately, the opening chord of the Largo is not together, the only serious blemish in the performance. A few phrases in the finale sound awkward; perhaps consensus has since smoothed over an odd moment or two—the matter is too subtle for me to decipher in the score. Again Harty races through the coda; this time it sounds like a cheap trick, something one might do in a live performance but not on a recording. Such a distinction was probably not yet recognized by most performers at that time.

The bonus track has Myra Hess and Harty playing the original piano four-hands version of a Dvořák Slavonic Dance. They are obviously enjoying themselves, as do we.

Mark Obert-Thorn has produced transfers that astound with their life and color. There is considerable distortion in the strings, but that was common to such early electrical recordings. Since Obert-Thorn goes to great lengths to find the best possible sources, these are probably the best we will ever get. In his (always fascinating) notes, he claims that the symphony, after many pitch corrections and “volume adjustments to correct the frequent gain-riding of the original engineers,” has the best recorded sound of anything here. It certainly captures the fine hall ambience. As producer of his CD, he has cleverly put the recordings (except the bonus track) in reverse chronological order—from 1933 to 1927—so that our ears may adjust gradually to the ancient recordings, preparing us for this disc’s pièce de résistance, the “New World.”

James H. North

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:1 (Sept/Oct 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.