This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

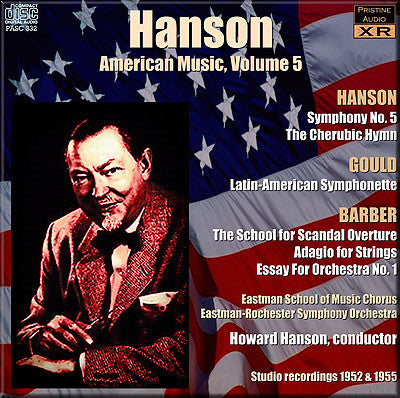

Hanson conducts his own 5th Symphony, plus music by Morton Gould and Samuel Barber

More American treasures from one of the finest interpreters of this music

The Barber and Gould recordings, both made on the same day in the autumn of 1952, displayed a distinct loss of top-end treble. In the case of the Gould this was particularly acute with a very steep drop-off of around 15dB above 10kHz that suggests a quite severe filter was used in mastering the original LP. I've done what I can to try and restore what remains above these frequencies in both recording, more successfully perhaps in the Barber. The 1955 recordings of Hanson's own works show a more typical "Living Presence" lift of the lower treble, though happily not as severe as on some of their recordings of this era, and it's an anomaly which happily makes for lower hiss levels after XR remastering has corrected the tonal balance.

All of the recordings displayed degrees of pitch instability consistent with the tape recording equipment of the day, allowing the orchestral tuning to wander slowly between about A=440Hz and A=446Hz. Standard concert pitch seemed a reasonable point to re-tune the recordings to, something which appeared to be confirmed by the copious amounts of mains electrical hum (with multiple harmonics) I have removed. Each of these recordings was transferred from original, near-mint 1950s US Mercury pressings.

Andrew Rose

- HANSON Symphony No. 5, Op. 43, "Sinfonia Sacra"

-

HANSON The Cherubic Hymn

Recorded May 1953 (Cherubic Hymn) and 1954

NB. Some sources suggest 8 May 1955 - this is not supported by the original LP sleevenotes

Issued as Mercury MG-40014

Eastman School of Music Chorus

-

GOULD Symphonette No.4: Latin-American Symphonette

- BARBER Overture to "The School for Scandal", Op. 5

- BARBER Adagio for Strings

-

BARBER Essay for Orchestra No. 1, Op. 12

Recorded 20 October 1952

Issued as Mercury MG-40002

Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra

Howard Hanson conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, April 2011

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Howard Hanson

Total duration: 70:49

Review (Barber & Gould - original LP issue)

I'm not sure that the two sides of this record fit very well together; but each, considered separately, is certainly a winner. The recording is throughout clear and vital, though perhaps lacking something in warmth; a deficiency that does altogether less damage here than it would in the classics, and which is in any case set off by many virtues in other respects—the brass and percussion in particular coming off extremely well.

Samuel Barber is the only contemporary American composer even reasonably well represented in the English catalogues but even so, the gaiety of the School for Scandal overture throws for us a new light on him. The quick-witted vein is an attractive one, and the piece is well presented by the orchestra.

So is the Adagio for Strings. This is more familiar; as well as some SPs there is a LP (Decca LX3042) called, I suppose unarguably correctly, Music of the Twentieth Century, which includes this piece in a hurried but rich-toned performance by the Boyd Neel Orchestra, along with an enveloping hum and some incongruous piano and 'cello pieces. Here there is no aggressive hum, though the string sound is not quite so rich as on the Decca ; but principally there is a considerably more intense performance, which reveals the moving elegy the better.

The Essay for Orchestra is not quite so convincing; it seems on the short side for what it has to say—the allegro molto section does not immediately declare itself capable of supporting the weight of the andante sostenuto which precedes it. But the three pieces taken together, and most admirably performed, give a most useful conspectus of Barber's achievement in the smaller forms.

One had always supposed that Morton Gould must have written something other than the Pavane, and here it is. A four-movement Sinfonietta is no novelty, but one based on four Latin-American dances is orchestral arrangements of a rumba, tango, guaracha, and conga by good musicians are no novelty, but ones done with musical rather than commercial ends in view seem, unfortunately, to be so.

Those four dances form the four movements, taking on something like the classical balance. The rumba has a first-movement fullness; the tango, of the Argentinian variety, is developed into a singularly attractive slow movement, with wisps of sound that are so wholly appropriate, but which could never be written for the audiences to whom Gould, or any other first-class arranger, normally has to direct his music, tango-style or otherwise. A guaracha is less familiar, but it forms an effective scherzo; the finale is a conga that begins and ends in a blaze, but has sober expanses in the middle, and is not quite the irresistible "orgiastic" affair the sleevenote led my baser instincts to hope for.

The whole work is played in great style the Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra seem completely at home with it. Few symphony orchestras can encompass this sort of music wholly satisfactorily - usually the brass section make it clear that the transition is too much of a strain. But here the style is changed with no apparent strain at all; and the brass and percussion are certainly beautifully caught by the fine recording.

The choice of coupling remains curious. But it has, arguably, one advantage; with two sides so diverse and each so good in its own way, it would be cantankerous indeed to dislike both of them at once.

M.M. - The Gramophone, June 1954

Fanfare Review

Howard Hanson was a national treasure. This disc is an important part of his legacy.

Jorge Luis Borges’s fictional author Pierre Menard declared that “censuring and praising were sentimental operations which had nothing to do with criticism.” Faced with this Howard Hanson CD, I must confess that I become a sentimental critic. Howard Hanson was not just a great advocate for American music; he also was a marvelous conductor. His approach to music is flexible—every bar means something. His dynamics are always just so, never approximate. Hanson is as much a master of orchestral balance as George Szell. In fact, for sonic reasons I prefer to hear Hanson’s monaural recordings instead of his stereo ones. Mercury’s single-microphone technique is more truthful to Hanson’s balances than its later three-microphone stereo is. This CD is a marriage of often great music, great performances, and truthful sound. One never can have enough of Howard Hanson the conductor.

Not that I intend to belittle Howard Hanson the composer. His Fifth Symphony, the “Sinfonia Sacra,” puts me in mind of the mystical, later works of Einojuhani Rautavarra, although Hanson’s piece is more carefully constructed. The string writing is masterly, and there is great beauty of sound throughout. As an expression of the self, the “Sinfonia Sacra” resembles a Shakespeare soliloquy. Though a romantic composer, Hanson here achieves a kind of mature Sibelian objectivity. It’s a lovely work. In the Cherubic Hymn, Hanson’s choral writing is straightforward and declarative. Unfortunately, the online program notes omit the hymn’s text. Hanson’s piece possesses a slight oriental coloring, as in some of the choral works of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Hanson’s hymn is reverential rather than ecstatic, relying on massed choral sound for excitement. As usual, Hanson’s performances of his own music can be considered authoritative.

One of the lamentable facts about our current concert life is the decline in performances of Morton Gould’s compositions. His music always is direct and beautifully constructed. He orchestrates in points of color, like Ravel, and his sound is splendidly transparent. I first heard the Latin-American Symphonette in Maurice Abravanel’s workmanlike recording, the flip side of the LP containing his classic version of Gottschalk’s First Symphony, “A Night in the Tropics.” Gould himself recorded the middle two movements, in demonstration-quality sound. Hanson’s performance is outstanding. In the Rhumba, Hanson displays great rhythmic subtlety, and elicits expressive solo playing. The movement recalls Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole. Next, the Tango seems less sexually overt than like a reverie. It is melodically captivating, sort of an idealized tango rather than a physical one. The Guaracho functions as a scherzo. Its winsomeness recalls Leroy Anderson, although Gould’s music is far subtler. For the last movement, one can envision a line of conga dancers, and Gould really breaks out the percussion. In Hanson’s hands, this symphonette is an important piece of music.

Hanson always has a sure touch in Samuel Barber. His Overture to The School for Scandal reminds me of a concert performance I heard by Joseph Silverstein conducting the Waterloo Festival Orchestra. With measured tempos, Hanson dwells lovingly on details, particularly the polyphony in the strings. The solo oboe in the second section sounds especially beautiful. In the Adagio for Strings, Hanson secures a full-toned rendition, with lots of body to the string sound. Hanson doesn’t go after angst, as Thomas Schippers does, but rather elegiac beauty. In the Essay No. 1, Hanson is passionate, but at all times the structure and harmony are clear. This is the best performance I know of the piece. Throughout the disc, Andrew Rose accomplishes beautifully balanced transfers of these recordings. His remasterings possess a warmth rarely found on Wilma Cozart Fine’s Mercury Living Presence CDs. I hope I have justified my sentimentality in approaching this collection. Howard Hanson was a national treasure, and his memory deserves a hallowed place in our musical life. This disc is an important part of his legacy.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:1 (Sept/Oct 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.