This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

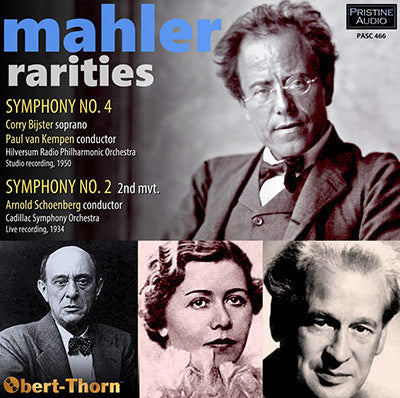

Two incredibly rare symphonic Mahler recordings unearthed and restored!

"The

performance is exceptional: pointed, fabulously controlled, yet

bursting with Viennese swagger and charm ... it’s the only surviving

example of one of the 20th century’s two great composers conducting

someone else’s music"

- Fanfare

The present release brings together two supreme rarities within the Mahler discography, one of which only exists in a single source, and the other so scarce it might just as well be the sole copy.

The broadcast of Arnold Schoenberg conducting the second movement of Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony stems from a unique radio transcription recording, probably taken down on a pre-grooved aluminum disc, which has circulated on a tape transfer. There is a gap in the middle, music most likely lost during a changeover to another record while using a single cutter.

The performance is rare not only in the scarcity of its source, but also for being the only recorded example of Schoenberg conducting a work by a composer other than himself. Unlike other acolytes and members of Mahler’s inner circle who left complete recordings of one or more of his symphonies (Bruno Walter, Willem Mengelberg, Otto Klemperer and Oskar Fried), Schoenberg left only this movement, making it all the more valuable.

The choice of this work for the opening of a concert with the “Cadillac Symphony” (most likely a sponsor-dictated pseudonym for NBC’s in-house Blue Network Orchestra), given shortly after Schoenberg’s arrival in America in 1934, is a tribute to Mahler’s early championship of the younger composer. Perhaps surprisingly for someone not primarily remembered as a conductor, Schoenberg leads a performance with a distinct personality, featuring a controlled rubato and a sure sense of pacing. (I might add that as noisy as this broadcast still sounds, I have cleaned up a good many of the transient noises that plagued the original transfer, as well as correcting the pitch.)

If the huge rallentando at the end of the opening phrase of Paul van Kempen’s 1950 recording of the Mahler Fourth brings Mengelberg to mind, there is good reason. For a few years beginning in 1913, van Kempen played in the violin section of the Concertgebouw orchestra, and knew the elder conductor’s way with the symphony very well. After that, however, it becomes more distinctly a van Kempen interpretation, with swift tempi and flowing lines.

This was van Kempen’s sole commercial recording of a Mahler work. It was never released on LP, and its only previous CD appearance was as a supplement to a very expensive Mahler discography. It has been restored here from a CD-R containing the unjoined 78 rpm sides provided by a private collector, as original sets are so scarce none could be located to transfer directly.

The recording is problematic in many ways. There is much volume manipulation by the original engineers, some of which I was able to counteract; but other portions (principally the climax toward the end of the third movement) were so extreme as to be unfixable. Add to this the distant miking of the soloist in the fourth movement and some faint recording elsewhere, and one can understand why this recording never received an “official” reissue. This new transfer at least makes it more accessible to interested listeners than it has ever been before.

Mark Obert-Thorn

MAHLER Symphony No. 2 in C minor, "Resurrection" - 2nd mvt.

Arnold Schoenberg, conductor

Cadillac Symphony Orchestra

From the NBC broadcast of 8 April 1934 in New York City

MAHLER Symphony No. 4 in G major

Corry Bijster soprano

Paul van Kempen conductor

Hilversum Radio Philharmonic Orchestra

Recorded January, 1950 in the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam

Matrix nos.: 035751/62

First issued on Telefunken SK 3862/7

Fanfare Reviews

On the cusp of “Mahler that never was,” two rare recordings escaped oblivion, much to our benefit

Still a controversial figure in his native Holland—as is his old boss, Willem Mengelberg—the Dutch conductor Paul van Kempen began his career playing in the second violin section of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. During the World War I he served as the concertmaster of various German orchestras and by the late 1920s had moved on to conducting. Those who take issue with his behavior during World War II—in addition to conducting the Dresden Philharmonic from 1934 to 1942, he also led regular morale-boosting concerts for the Wehrmacht—tend to forget (if they knew it in the first place) that he had become a German citizen in 1932. Unlike Mengelberg, whose close collaboration with the Nazis led to a lifetime ban on further work in the Netherlands (which was later reduced to six years), van Kempen was allowed to return, though not without serious protest. At one concert in 1951, the heckling became so intense that more than half the orchestra walked off the stage (whether in solidarity with the audience or out of sheer exasperation remains unclear). Ironically enough, it was in that same year that van Kempen began that extraordinary COA series of Tchaikovsky recordings upon which so much of his posthumous reputation rests, including an eviscerating version of the “Pathétique” Symphony and the maddest ever Capriccio italien, a performance whose manic tempo upheavals—while admittedly thrilling—should not be listened to without a precautionary dose of Dramamine.

If the mammoth rallentando in the opening bars of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony suggests a similar moment in the famous Mengelberg recording, then what follows for the most part is a fairly straightforward, superbly-played Mahler Fourth in flawed but generally acceptable early 1950s recorded sound. The producer, Mark Obert-Thorn, explains the sonic limitations as follows: “There is much volume manipulation by the original engineers, some of which I was able to counteract; but other portions (principally toward the end of the third movement) were so extreme as to be unfixable. Add to this the distant miking of the soloist and some faint recording elsewhere, and one can understand why this recording never had an ‘official’ issue.” As the climax of the third movement is the crowning glory of the entire work, after all—and if Obert-Thorn says he can’t fix it, then nobody can—for many listeners this will rule the recording completely out of court. The distant miking proves a mixed blessing in the final movement, as Corry Bijster manages the fairly astonishing feat of sounding tremulous and matronly simultaneously.

Arnold Schoenberg’s recording of the second movement of the “Resurrection” Symphony poses other technical problems, including a gap in the middle—“most likely lost during a changeover to another record while using a single cutter” (Obert-Thorn again)—and the usual aircheck clickpops and other noise. The performance, on the other hand, is exceptional: pointed, fabulously controlled, yet bursting with Viennese swagger and charm. Furthermore, the fact that it’s the only surviving example of one of the 20th century’s two great composers conducting someone else’s music sets the seal on its unquestioned historical importance. Is it worth Pristine’s premium price for 11 minutes of Schoenberg’s Mahler movement and a Mahler Fourth you’ll probably only listen to a couple of times—if that? Unquestionably.

Jim Svejda

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:1 (Sept/Oct 2016) of Fanfare Magazine

Titling this new release from Pristine Audio Mahler Rarities is no exaggeration. As producer Mark Obert-Thorn tells us in a brief note, “The present release brings together two supreme rarities within the Mahler discography, one of which only exists in a single source, and the other so scarce it might just as well be the sole copy.” Inveterate collectors love to hear such words, and it’s primarily for them that these historic recordings will be enticing. For his restoration Obert-Thorn worked from problematic sources. The second movement of the “Resurrection” Symphony conducted by Arnold Schoenberg—the only surviving account, evidently, of him leading any piece on disc other than his own music—comes from a privately circulated transfer of pre-grooved aluminum 78s whose origins are murky.

Schoenberg had just come to America, and despite his fearsome reputation, we hear a radio introduction by Milton Cross where he is called “the renowned composer,” and the orchestra, presumably named after a car-company sponsor, is probably a pseudonym for NBC’s Blue Network Orchestra. The new restoration has reduced surface noise and corrected pitch, yet it’s still gritchy and narrow in dynamic range. At one point in the middle there’s a gap, presumably while the disc was being changed on a single cutter.

For all that, it’s invaluable to hear one of Mahler’s earliest champions conduct this music, since unlike other disciples and acolytes—Klemperer, Walter, Mengelberg, Fried, and Horenstein—Schoenberg left no commercial Mahler recordings. The pacing and phrasing here are not unusual. There is controlled rubato and a prevailing affectionate mood (which may surprise Schoenberg-phobes). Enough personality comes through for us to judge that Schoenberg’s approach is slightly brisk and efficient, being neither as warm as Bruno Walter’s Mahler nor as malleable as Mengelberg’s.

Van Kempen’s 1950 studio recording of the Fourth Symphony never received an official LP release. Its only previous appearance was as a supplement to a very expensive Mahler discography. That source was unobtainable, so Obert-Thorn worked from a CD-R in a private collection that held the unjoined 78-rpm sides. There were sonic challenges here, too, mainly consisting of manipulated volume levels by the original engineers and too-distant miking of the soprano in the finale. But since this was van Kempen’s only commercial recording of a Mahler symphony, it has obvious historical value.

Van Kempen played under Mengelberg in the violin section of the Concertgebouw for a few years beginning in 1913, but only the rallentando at the outset of the first movement declares any resemblance between them. Van Kempen’s pacing is swift, in the vein of Benjamin Britten and Pierre Boulez, who both recorded notably fast first movements. (Van Kempen takes 15:24 compared with Boulez’s 15:17 with the Cleveland Orchestra on DG.) On the evidence of this performance, van Kempen’s Mahler is intriguingly personal, the very opposite of subscription fare. The first movement is one of the least bucolic I’ve ever encountered, with actual fierceness at times. Every note is decisively placed. On its own, velocity is neither positive nor negative; van Kempen uses it, like Toscanini at his best, in the service of intense concentration.

For whatever reason, the sound gets dimmer and more faraway in the second movement, robbing it of impact, most notably at the beginning. The solo part for a mistuned “devil’s fiddle” isn’t brought forward but blends into the ensemble, another drawback. Through all this one can still detect—and enjoy—van Kempen’s natural, flowing manner in this music. One has to be prepared for patchy, diminished sonics, however. Because the Adagio is string laden, it comes across better as a listening experience. The tenderness and lyric simplicity of van Kempen’s interpretation would arouse envy in many Mahler conductors today. Unfortunately, the climactic opening of Heaven’s gates is suppressed dynamically. The finale is imbued with charm—not a quality I usually associate with van Kempen—and soprano Corry Bijster is a relaxed, warm-voiced soloist. If only she had been miked a little closer.

This release can’t be recommended to every lover of Mahler, but if you have any historical inclinations, it will prove fascinating. On the cusp of “Mahler that never was,” two rare recordings escaped oblivion, much to our benefit.

Huntley Dent

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:1 (Sept/Oct 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.