This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

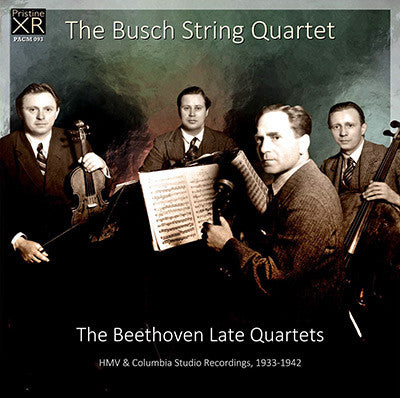

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

Pioneering Busch String Quartet brilliant with Brahms

"The Busch Quartet are at the top of their form ... exceedingly good" - The Gramophone

These recordings of the late quartets of Beethoven were recorded in HMV at Abbey Road Studios between 1935 and 1937, supplemented by Columbia's recordings of 1941/42 at the Liederkranz Hall in New York City. As with some previous Pristine restorations I've found the best results have come from LP transcriptions of the original 78s, transferred and issued in the days before digital remastering. With limited options for improving sound quality, the onus on engineers was to get the very best from the original masters, often by either playing the metal plates directly or by pressing quiet vinyl copies from them in order to make their transfers. Although it's unclear here which methods were used, both the CBS and EMI vinyl reissues of later decades proved excellent starting points for the present set.

In each case XR remastering has made significant improvements in sound quality, with the higher frequencies now far clearer than before, especially in the otherwise better-recorded Columbia takes. The slightly boxy sound of the HMV studio recordings has also opened out considerably, and overall the impression is of a much fuller, richer and more dynamic sound than might be anticipated from recordings of this era.

The pitching of the original transfers varied considerably. There was also some pitch variance within individual recordings. Here I've chosen to pitch all of the recordings to standard concert pitch. The use of pitch stabilisation software has also enabled the elimination of wow from the original discs, as well as other pitch anomalies.

The Late Quartets don't normally include the 7th Quartet; with the five quartets, 12-16, complete there was a perfect Quartet No. 7-sized gap in CD1, hence its inclusion here.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 7 in F, Op. 59, No. 1 "Rasumovsky"

Recorded 15/25 May 1942, Liederkranz Hall, New York

Cat. Nos. Columbia 71474-D - 71479-D

Matrices XCO.32832-37; 32869-73

-

BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 12 in E flat, Op.127

Recorded 2/16/17 November 1936, Abbey Road Studio 3

Cat. Nos. HMV DB.3044-48

Matrices 2EA.4401-07

-

BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 13 in B flat, Op.130

Recorded 13/16 June 1941, Liederkranz Hall, New York

Cat. Nos. Columbia 71220-D - 71224-D

Matrices XCO.30695-704

-

BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 14 in C sharp minor, Op.131

Recorded 2 March 1936, Abbey Road Studio 3

Cat. Nos. HMV DB.2810-14

Matrices 2EA.3120-29

-

BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op.132

Recorded 7 October 1937, Abbey Road Studio 3

Cat. Nos. HMV DB.3375-3380s

Matrices 2EA.5464-68/71-76

-

BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op.135

Recorded 13 November 1933, Abbey Road Studio 3

Cat. Nos. HMV DB.2113-16

Matrices 2B.5436-43

The Busch String Quartet:

Adolf Busch violin

Gösta Andreasson violin

Karl Doktor viola

Hermann Busch cello

ARTICLE: "The Busch Quartet" (excerpt)

Only the Busch ensemble, in my experience, have presented the Beethoven quartets on record in their full majesty - and daring. Among the qualities that made Adolf Busch a great violinist were his uniquely long bow strokes, controlled with profound intensity and invested with a strong spiritual charge. Believing that the late quartets had to be taken to extremes, he played fast movements very fast - often up to Beethoven’s controversial markings - and slow movements very slowly. With a rhythmic sense as rigorous in broad tempi as it was exhilarating in quick tempi, he inspired his colleagues to match him in exceptional feats of concentration. Acting as his own producer, with a trusted HMV engineer such as ‘Chick’ Fowler, he generally made just one take of each side in a slow movement, so as to keep the intensity going from take to take. The luminous beauty of the Busch Quartet’s playing can snatch your breath away in any of their repertoire, but the uninitiated should start with late Beethoven.

Tully Potter, Gramophone, November 2013

REVIEW 1976 LP reissue

Before the war the Busch Quartet played Beethoven better than any other ensemble, and they still sound marvellous. They were always at their best in the late quartets and with the arrival of these two discs their newly transferred performances of all but the Grosse Fuge are now available. The playing seems more spacious than that of the best modern ensembles; they uncover the musical thought at their leisure. This impression results in part from the very slow tempo in the stow movements, but they can also sound almost leisured even when, according to my watch, the tempo is normal, as in the Scherzo of the F major. I think this is because they seem less prone than modern ensembles to push their own technical accomplishments. Everything is subservient to the music. The slow movement of the E flat is most beautifully done; quaver lengths hardly vary in spite of all Beethoven's changes of tempo, but if the tempo is slow enough at the start they don't need to. The slow movement of the C sharp minor is so thoughtfully played that the Quartet as a whole takes three or four minutes longer than usual, and very moving it sounds. In the very difficult Scherzo that follows the rhythm is uneven in places; here alone complete success eludes the players.

Though the Busch Quartet scooped much less than most ensembles of the 1930s the 1976 listener will certainly notice such scoops as there are. The trick is applied with curious inconsistency. For instance in the first allegro theme of the E flat Busch himself sometimes slides up from the first crotchet to the second (as in the first bar) and sometimes doesn't (as when the same phrase is repeated four bars later); when this phrase is developed by all four players there is similar inconsistency. It must follow that during rehearsals there was never any discussion between the players as to whether they should scoop or not; it was just left to chance like a touch of eighteenth-century improvisation. I do not myself find the trick in any way worrying. Indeed in the first movement of the E flat one can even persuade oneself that it adds a touch of emotion to the sound. The illusion of leisured thinking is here at its very best; the last page seems to me the very perfection of playing. Here and elsewhere pianissimos are a constant wonder.

Bearing in mind that all this music was recorded forty years ago and more, the quality is splendid; furthermore these excellent performances of superb music are very reasonably priced. Strongly recommended.

R.F., Gramophone, November 1976, review of LP reissue on World Records

Fanfare Review

As exemplars of mid-1930s performance practices, the Busch’s Beethoven is unmatched

Reviewing this set of Beethoven’s late quartets performed by one of yesteryear’s pre-eminent string quartet ensembles requires me to make an exception to my longstanding, and by now tiresome, pledge not to review recordings of these works wherein the Grosse Fuge from the op. 130 Quartet is shifted to after the alternate finale or worse, placed on another disc altogether. Neither is the case here, since the Grosse Fuge is nowhere to be found on these three discs. Whether the Busch String Quartet ever recorded the Grosse Fuge in its original form, I don’t know, but the ensemble did record it in an arrangement by Felix Weingartner, which was included in a three-disc EMI set of the complete late quartets, reviewed by Mortimer Frank in 31:6.

As Frank and other Fanfare reviewers have noted, these Busch Beethoven studio recordings, made between 1933 and 1942, have long circulated in various configurations on various labels—Biddulph, Dutton, CBS/Sony, EMI, and Preiser. These are the same recordings at hand, cleaned up, of course, and remastered by Andrew Rose for these Pristine discs.

If you’re already familiar with the performances on one or another of the above-named labels, your only question is likely to be about the sound of these Pristine restorations; and on that count I can tell you that what Rose has achieved is quite remarkable.

No, you won’t think you’re listening to the latest SACD to come off the press, but comparing Pristine’s “XR” processing to the Dutton transfers I’ve heard, Pristine’s sound is definitely more open (i.e., not as damped sounding), lending greater separation to the voices, and providing an extended sense, perhaps perceived rather than actual, of high and low frequency response. Purely on the merits of recorded sound, these Pristine versions are superior and preferable to the Dutton versions I’ve heard. I can’t speak to the Biddulph transfers because I haven’t heard them.

If you’re not already familiar with the performances, I can tell you that the Busch Quartet was in its prime and recording these Beethoven quartets at virtually the same time that its approximately contemporaneous rival, the Budapest String Quartet, was recording some of its earliest Beethoven, also in the mid-1930s. Those performances, recorded in London by HMV, can be heard in transfers on Biddulph, and comparison to the Busch Quartet in terms of aesthetic style and approach is instructive.

One already hears in the Budapest’s playing readings that are transitioning to a more modern interpretive stance and understanding of the music. Tempos are a bit swifter, there’s less portamento, and vibrato is more modulated in accordance with dynamic and expressive markings. The Busch’s readings, in contrast, project a warmth that’s somewhat downplayed in the Budapest’s readings, and it’s that warmth that gives the Busch’s performances a wonderful inner glow and feeling of devout concentration. But by today’s standards, the unalleviated vibrato and especially the profusion of portamento—too few position shifts and intervals of greater than a third are navigated without a slide—really do become cloying in fairly short order.

As exemplars of mid-1930s performance practices, the Busch’s Beethoven is unmatched. Accepted on their own terms, these readings represent the very best in string quartet playing of their time, and these magnificent Pristine refurbishments enhance our understanding of why this ensemble was—and for many still is—so highly regarded. Jerry Dubins