This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

- Historic Review

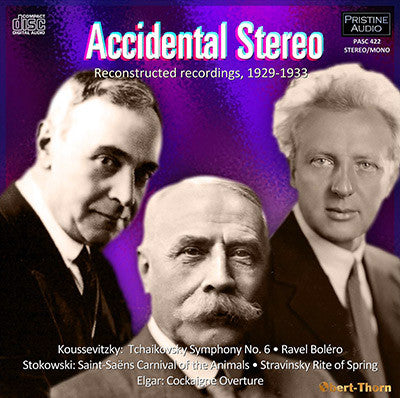

Amazing "accidental" stereo 78rpm recordings made by Elgar, Koussevitzky and Stokowski

New technologies and techniques produce astonishing stereo results from these unexpected early electric recordings

Shortly after the introduction of electrical recording, it became standard practice to make backups for wax matrices by simultaneously recording on a second cutting table, with the takes from the first being numbered 1, 2, etc. and the ones from the second 1A, 2A, etc. In the vast majority of cases, the two cutters were fed from the same microphone. Occasionally, however, each was run from its own microphone; and where those matching takes survive and have been released, it is possible to combine them to produce what has come to be called “accidental stereo”.

Since this phenomenon was first brought to light some thirty years ago, a number of matching “plain” and “A” takes have been proposed as possible stereo pairs; but until recently, the technology did not exist to prove whether they were or not. The problem lay in perfectly synchronizing the two sides: there could be differences in speed between the original cutting turntables, within each recorded side, or in the playback turntables. There was also the problem of “wow” caused by warping of the original discs or imperfect centering on the turntable. Any one of these factors could lead to a false positive – identifying two recordings made from the same setup as stereo based on subtle variations which caused them to be out of sync with each other.

The recent development of Celemony’s Capstan pitch-stabilizing program, used in conjunction with phase alignment software, finally enables these problems to be solved with a degree of accuracy hitherto unattainable. In successfully synchronizing some proposed stereo sides, others have proven to be only in mono. For example, Side 4 of Koussevitzky’s 1930 Tchaikovsky Pathétique came out in takes labeled 1 and 1A; however, analysis has proven that at least one of them was mislabeled, and that they are in fact identical. Similarly, two 1941 Stokowski recordings previously released in what was believed to be accidental stereo were shown to be no more than slightly out-of-sync mono.

The present release brings together nearly all the sides that have been identified publicly so far as Classical accidental stereo recordings. As the name implies, accidental stereo was never intended to be heard in synchronized form, and was not miked the way a stereo recording would have been. Most likely, one microphone was centered on the orchestra, while the other was pointed slightly off to one side. However, the joined-up results do suggest some directionality that accords with what is known of the orchestras’ seating patterns under these conductors. For example, a 1947 picture of Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony on stage at Symphony Hall displays the basses lined up to the left and back with the timpani stationed on the right – exactly as we hear them in the Tchaikovsky.

One can best appreciate the added dimension accidental stereo brings at those points where the music blossoms from mono into stereo. Suddenly, what has been the auditioning of a historical artifact takes on a presence and a reality that puts us in the concert hall 85 years ago – a time machine like no other.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

SAINT-SAËNS Carnival of the Animals

Aquarium – Personages with Long Ears – The Cuckoo in the Heart of the Woods [stereo]

Olga Barabini and Mary Binney Montgomery(pianos)Recorded 27 September 1929 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CVE-51883-2/2A

First issued on Victor 7201 in album M-71 -

STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring

Part 1: The Adoration of the Earth

Introduction [stereo]

Games of the Rival Tribes – Procession of the Wise Elder – Adoration of the Earth – Dance of the Earth [stereo]Recorded 24 September 1929 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CVE-37471-4/4A and 47975-1/1A

First issued as Victor 7227 and 7228 in album M-74

The Philadelphia Orchestra ∙ Leopold Stokowski

-

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 (Pathétique)

1st Mvt.: Adagio – Allegro non troppo [mono/stereo]

2nd Mvt.: Allegro con grazia [stereo]

3rd Mvt.: Allegro molto vivace [stereo/mono]

4th Mvt.: Adagio lamentoso – Andante [mono]Recorded 14 - 16 April 1930 in Symphony Hall, Boston

Matrix nos.: CVE-56824-2, 56825-2, 56832-2/2A, 56833-1A, 56826-2/2A, 56827-2/2A, 56828-1/1A, 56829-2, 56830-2A and 56831-2

First issued as Victor 7294 through 7298 in album M-85 -

RAVEL Boléro [mono/stereo]

Recorded 14 April 1930 in Symphony Hall, Boston

Matrix nos.: CVE-56820-1A, 56821-2/2A and 56822-2/2A

First issued on Victor 7251/2 [later in album M-352]

Boston Symphony Orchestra ∙ Serge Koussevitzky

-

ELGAR Cockaigne Overture (In London Town), Op. 40 – conclusion [stereo]

Recorded 11 April 1933 in Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

Matrix nos.: 2B 4176-1/1A

First issued on HMV DB 1936

BBC Symphony Orchestra ∙ Sir Edward Elgar

When Mark Obert-Thorn first suggested a collaboration on this project a few months ago, neither of us really knew what to expect. Mark's theory that Capstan might prove helpful in synchronising these independently-cut recordings was just that, a theory. I was less sure that Capstan would be as consistant as would be required, particularly in certain passages of heavily-rhythmic music, or where microphone placement might cause different instruments to dominate the mix, thus stressing different harmonics and changing, if only minutely, the software's analysis of pitch.

As I began to work on the first recordings sent to me, it was clear that we were onto something - and also that my involvement would have to be greater than originally envisaged. With Capstan doing at least 95% of the "grunt work" on most of the sides, there was still a considerable amount of additional work involved, preparing the sides specifically for this project prior to their analysis and repitching to minimise risk of error, and then identifying minor mismatches between two post-Capstan sides and adjusting manually for this when mixing them together to produce the stereo result. Finally each side had to be fine-tuned using phase-alignment software to identify commonality between the two channels to a very fine resolution and adjust them to fit exactly.

Previous to this technology the results have been at times ambiguous. We made a number of dicoveries in the process of producing this release which strip away this ambiguity and introduce, for the first time, certainty to the identification of these recordings as genuine "accidental stereo". After apparently successfully mixing "stereo" sides together I came to a pair of Stokowski recordings that had already been identified and released elsewhere as accidental stereo recordings. My technique proved otherwise. By bringing a level of unprecendented accuracy to the pitching and matching of the two "channels" I discovered that both were actually identical, and thus the claims for accidental stereo here were erroneous, based on phase errors and wishful thinking. No matter how I approached the recordings in question, I always ended up with the same result: mono.

By contrast, the final recording on our release, Elgar conducting his Cockaigne Overture, has been specifically highlighted as a recording in which "accidental stereo" would be impossible, due to working practises at EMI's Abbey Road studios at the time, based on testimony of people who had worked there. Some very eminent names have been quoted, stating that any suggestion of accidental stereo here can only be down to the kind of phase error and wishful thinking that we found in the case of the Stokowski. They are wrong. There is absolutely no doubt that this is genuine accidental stereo in the case of this wonderful recording, and it's a fantastic find, given the work and its composer/conductor here.

Finally, I was originally thrown by recordings which seemed to wander around the stereo soundscape from left to right and then back again. Was this an error in my method? No. It became particularly obvious in the third side of the Tchaikovsky symphony that someone was "gain riding" the output to the disc cutter that produced our left channel, whilst the right channel was being recorded "straight" from the microphone, without any interference with levels. Once this was established it was a relatively straightforward job to correct for this and stabilise the stereo imagery, with the added bonus of accurately losing the effect of gain riding by a nervous sound engineer keen not to overload his recording equipment.

The end results have been some of the most satisfying of my career in audio restoration. There is a real sense of wonder in the recordings where a mono sound suddenly opens out into a glorious - if perhaps a little confused - stereo picture. And when listening on headphones, one finds oneself more "there" in the recording studio than I've ever felt before in any recordings of this era. It is a truly remarkable result that I would recommend highly to anyone, regardless of their interest (or otherwise) in the pieces being performed or the musicians involved. They only sweeten the pie!

Andrew Rose

Historic Review: Stravinsky & Tchaikovsky

NB. This is how the original reviews of these two highly unusual accidental stereo releases appeared in The Gramophone in 1931. It is an incredible coincidence that they not only appeared in the same review column, but that one followed directly on from the other. It's also instructive to find the music being reviewed over and above the performances at this point in time.

It is not disrespect that forces me to deal with the Stravinsky work so briefly. The month is overwhelming! I wish I had space to argue the Rite and the wrong of it. Parts of the work are so extraordinarily powerful (taking the composer on his pagan ground) that it is a pity the rest does not come up to sample. Is it too long? And are we not now too far from the ballet to get the flavour of the work? The music is obviously born for the ballet, like all the best of Stravinsky. Outside that, and his nationalistic colour and rhythm, I can find next to nothing in him. But the part that is powerful cannot be forgotten, and should not be under-estimated. As far as I can tell without the score at hand (and it is a score one cannot well claim to know by heart!) this performance stands up to the music magnificently. The parts are thus labelled :— First Part: Earth Worship—Introduction, Immanence of Spring, Adolescents’ Dance, Symbolic Scene of the Rape; D1920 : Dances in Honour of Spring, Mock Conflicts of Rival Communities, Procession of the Elder, Earth Worship, Dance of the Earth; D1921 : Second Part—The Sacrifice: Introduction, Mystic Circles of the Adolescents, Glorification of the Chosen Virgin ;D1922 : Evocation and Ritual of the Ancestors, and Sacred Dance of the Chosen One. There is in that strange opening something sad, primitive and elemental : there the composer gets nearest to imaginative reality. The short- windedness of so much of the music, and its rhythmic complications, which do not always come off, its (to some of us) depressing primeval peasantism, prevent us from enjoying half the work. Still, those who like the work as a whole will be glad to have this, than which it would be difficult to imagine a clearer, more rapt performance.

The Tchaikovsky is of course a “ big noise ’’ (not in the bad sense). Inevitably, a man like Koussevitzky is the right match for his compatriot. Here is another side of the Russian, but Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky are scarcely to be compared, in spite of the former’s admiration for the earlier writer. Here is cultivation—to excess, I feel: that is partly why some musicians find Tchaikovsky rather unhealthy. It is not only the gloom, which one can take in the stride : and there is no disparagement of workmanship, which indeed, we enormously admire. The ideas are not wearing well—so we feel. The gloopiness is just a little too slick; but what stuff to give ’em in the nineties! I like Koussevitzky’s basses, his precision with the brass, the strings’ persuasiveness and their whoops aloft, the lighter wind whiffs, the delicate phrasing in the 5-4 movement, with the touch of gravity here (needed for balance, since the March is rowdy, repetitive, but full of gusto). The First and last movements, by the way, take two discs each, the second and third one each. The March is never loud enough for me; the trouble is that it cannot, accumulate force at every one of the (too many) repetitions. At the last, JL want to see every door of the hall burst open, and a brass band march in at each : the organist springing on his seat and drawing every stop he possesses, Only thus can. we and the composer enjoy ourselves in the glad old time with which he delighted to paint the town red. This recording of the work has a wholeness, a built-up-ness, that seems to me to go past any other I know. There are some small defects of balance, but they matter little. If you hanker after a Pathetic,this is the top-notch of dexterity, to my mind; and after all these years there may not be, for some, much left in it but that. Let us praise the famous man, however, for his real virtues, and not now bother about the rest of him!

W. R. Anderson, The Gramophone, April 1931 - Orchestral section, His Master's Voice new releases

Fanfare Review

If only there had been more accidents like this!

What an odd and fascinating collection this is—“Aquarium,” “Personages with Long Ears,” and “The Cuckoo in the Heart of the Woods” from the Carnival of the Animals; the Introduction, “Games of the Rival Tribes,” “Procession of the Wise Elder,” “Adoration of the Earth” and “Dance of the Earth” from The Rite of Spring; and the last four minutes or so of the Cockaigne Overture, coupled with a complete “Pathetique” and Boléro. In his annotations the producer, Mark Obert-Thorn, explains what “accidental stereo” is: “Shortly after the introduction of electrical recording, it became standard practice to make backups for wax matrices by simultaneously recording on a second cutting table….In the vast majority of cases, the two cutters were fed from the same microphone. Occasionally, however, each was fed from its own microphone and where those matching takes survive and have been released, it is possible to combine them to produce what has come to be called “accidental stereo.”

I don’t know how many readers will want this CD; it’s the sort of novelty you might play to surprise your friends. If your curiosity gets the better of you, here’s what I suggest: start off with the Boléro, preferably with a headset. Side one of the original 78s is monaural. Then you arrive at side two and suddenly the sound stage widens and blossoms into a rich, slightly directional sonority that I found astonishing and continues that way to the music’s conclusion. Koussevitsky was apparently someone who didn’t heed Ravel’s description of the piece as “seventeen minutes of noise without music” and dispatches the piece in 13:25. There’s a story that Ravel once burst into Koussevitsky’s dressing room after hearing him race through the Boléro, shouting “It was a thousand times too fast … a thousand times!” The maestro’s cynical rejoinder was, reputedly, “Really sir … hardly a thousand times.” Anyway, I detest the performance (I don’t like his later recording, either) but was thrilled by the sound. For another dramatic comparison, try Koussevitsky’s 1930 Tchaikovsky Sixth, which starts out with two channels. Then, on side eight, midway through the third movement, we suddenly lose our second channel and the sound flattens out into (I have to say it) dull, flat monaural the rest of the way, and what a letdown it is. I’m surprised that, given the recording’s 1930 origin, Victor didn’t have him rerecord the piece later, instead favoring Ormandy, Stokowski, and Toscanini.

The rest of the CD is stereophonic and frustrating because the sound is so remarkable and unexpected. If you thought Stokowski’s Philadelphia stuff sounded good in one channel, wait until you hear what it could have sounded like with two, even with a narrow stereo spread. Even the brief Elgar excerpt, with its under-nourished strings, sounds remarkably vivid. If only there had been more accidents like this!

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:4 (Mar/Apr 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.