This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Stoki's Chicago debut - just 53 years into his professional career!

First release of two packed CDs-worth of quintissential Stokowski

Leopold Stokowski had for several decades been one of the world's most well-known and respected conductors when, on 2nd January 1958, he stepped onto the podium at Chicago's Orchestra Hall to conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for the first time as its guest conductor. Between 1958 and 1968 he was to appear with the orchestra in six seasons of concerts; this release brings out for the first time what has been preserved from his debut concerts at the beginning of 1958.

The recordings presented here are not, it would appear, actual live broadcasts from Chicago, but were taken from rebroadcasts shortly later from a New York radio station - despite the announcer's assertions that they are live in Orchestra Hall, these were probably voice-overs from the New York radio studio. The rebroadcasts omitted music by Wagner which had formed the bulk of the second part of the first concert, following the Toccata of the little-known Polish composer, Boleslaw Szabelski.

The first half of that opening concert (which was repeated on 3rd January) consisted of traditional fare - Stokowski's orchestrations of Bach's Chorale Preludes and the Brahms symphony. The second programme, again repeated over two concerts, was an all-Russian affair, beginning with the Shostakovich and Glière and continuing after the interval with the Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky suites.

As usual, the orchestra and audience got full value for money from Stokowski. In addition to his own orchestrations of the Bach, he was also responsible for the orchestration of Shostakovich's Prelude in E flat minor very shortly after its composition. The composer himself later orchestrated the piece for a 1944 film entitled Zoya, a name which has stuck to a degree to the prelude - however it is, of course, the conductor's orchestration we hear in this concert.

The selections from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet are somewhat skirted over by the announcer, as in fact they derive not from a single suite but from both the first and second suites. Meanwhile Stokowski has again gone his own way with his Swan Lake Suite, which does not correspond to the published suite. Indeed it took a certain amount of musical detective work to identify precisely which parts of Tchaikovsky's music had been used for some of the sections presented here.

Finally, it has been suggested that without Stokowski's efforts, Glière's mighty 3rd Symphony may well have been entirely forgotten. The full work runs to a sprawling 75 minutes or longer - by skilful editing, Stokowski reduced it to something more manageable and digestible and was thus able to programme it on several occasions and thus keep it alive.

Technically the sound quality of the recordings here is generally quite good to excellent, although there are some uneven areas. I have had to play with the running orders in order to fit all of the surviving material onto two discs, and have corrected an error by the announcer, who mistakenly introduced Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet as Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake - he himself had corrected this in the back-announcement to the piece.

Andrew Rose

- BACH Chorale Preludes

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 599

Komm, susser Tod, BWV 478

Mein Jesu! was vor Seelenweh, BWV 487

Wir glauben all' an einen Gott, BWV 437

- Boleslaw SZABELSKI Toccata (1938)

- SHOSTAKOVICH Prelude in E flat minor, 'Zoya', Op. 34, No. 14 (orch. Stokowski)

- PROKOFIEV Romeo and Juliet Suite

Suite No. 1, Op. 64bis: VI. Romeo and Juliet

Suite No. 2, Op. 64ter: VI. Dance of the Antilles Girls

Suite No. 2, Op. 64ter: VII. Romeo at the Grave of Juliet

- TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake Suite

1. Act 1 Introduction - Moderato assai

2. Act 1 No. 5 - Pas de deux

3. Act 2, No. 10 - Scène

4. Act 2, No. 13 - Danse des Cynges

5. Act 3, No 20a - Danse Russe

6. Act 3 No. 21 - Danse Espagnole

7. Act 4, No. 27 - Danse des petits cygnes

8. Act 4, No. 29 - Finale

- BRAHMS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

-

GLIERE Symphony No. 3 In B minor, Op. 42, “Il'ya Muromets”

Live concert recordings from Orchestra Hall, Chicago:

2nd January 1958 - Bach,Brahms, Szabelski

9th January 1958 - Shostakovich, Glière, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

conductor Leopold Stokowski

Transfers from the collections of Edward Johnson and John Kelly

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, August-September 2010

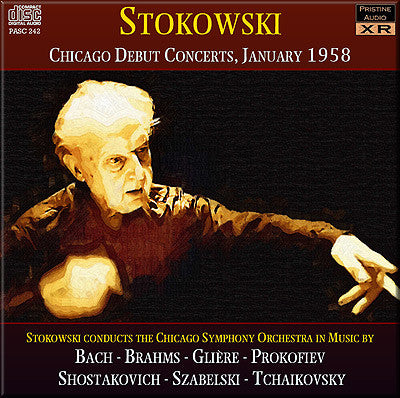

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Leopold Stokowski

Total duration: 2hr 37:58

Fanfare Review

Unfortunately, I was on Christmas vacation from college when Leopold Stokowski, at age 75, made his first appearance with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (he remarked that they must have been waiting for him to reach maturity). By the following week, I was back in town and did hear the Friday matinee concert on January 10. The concerts must have been considered a success because Stokowski kept returning in subsequent seasons and even made some studio recordings with the orchestra. Sadly, only one season of the Fritz Reiner era was taped, that of 1957–58, and it was done by a New York radio station (WBAI) that was operating on a very limited budget. WBAI’s engineer/producer would fly to Chicago, tape the Thursday evening concert, and then head back to New York the next day. I would guess that the concerts were broadcast on Saturday night in New York, but it’s been a long time. One night, Reiner, who must have been pleased that someone was broadcasting his concerts, offered WBAI’s man a lift back to his hotel. Not wanting to reveal what a low-budget enterprise he was involved in, the WBAI producer asked Reiner to drop him at the posh Palmer House. He entered the lobby, waited about five minutes, and when the coast was clear, exited and headed for the local YMCA where he was actually staying! Fortunately, the orchestra and now Pristine Audio have been able to use copies of the WBAI tapes to, at least, preserve one Reiner season in respectable sound (the CSO also did regular TV appearances, but those kinescope recordings are sonically compromised).

But back to Stokowski. No one’s Bach transcriptions throb quite like Stokowski’s, especially if he was conducting them. These four are Stokowski standards and he and the orchestra deliver the goods. They are effective even though they are a half-tone flat and, while I’m on the subject, the Shostakovich Prelude in E♭-Minor, orchestrated in a very Shostakovich-like way, plays back in D Minor. As far as I can tell, nothing else on either CD is below pitch.

The Polish composer Boleslaw Szabelski lived from 1896 to 1979. After late-Romantic beginnings, he began to compose atonal music during the 1950s. He was a student of Karol Szymanowski and was a teacher of the late Henryk Górecki. The Toccata, a busy 1938 showpiece for orchestra, predates his switch to atonality. Did Stokowski ever conduct it again?

The sheer warmth of the Prokofiev excerpts inspire wishes that he had recorded the complete score (but please, no cuts!). He recorded some selections with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1954. Unfortunately, all he did was “Romeo and Juliet,” “Romeo at the Tomb of Juliet,” which are included here, and three others. He recorded excerpts from acts II and III of Swan Lake with “his” symphony orchestra, brilliantly played but somewhat streamlined probably to squeeze as much music onto the LP as possible. As for the Chicago performance, I wish I could hear the entire ballet performed with such suppleness and warmth, and the playing is as good as you might imagine. For some reason, the Hungarian Dance is labeled “Danse Russe.”

The two symphonies take up the second CD. With respect to the Brahms, I haven’t heard Stokowski’s late-career recording with the National Philharmonic but I do have the early Philadelphia Orchestra version on hand. Aside from Chicago’s being a shade faster and little more “punctuated” for emphasis, the Chicago and Philadelphia performances are similar. They are pretty much mainstream readings. As expected, the Chicago taping is more detailed and has louder brass playing. Compared with the Philadelphia recording, there’s little use of portamento. The CSO really digs into the last movement.

Sometime during the first season of Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center, I decided to test the acoustics of Verizon Hall, the Philadelphia Orchestra’s new home. I thought that Glière’s “Ilya Murometz” Symphony would be a decent test piece and Neeme Järvi was scheduled to conduct it. I had already heard Stokowski conduct it twice, once in Chicago and once in New York, but for some people, including me, the “Ilya Murometz” is one of life’s guilty pleasures so I decided to take in a Friday matinee so I could return home after the concert. The concert was to open with Thomas Zehetmeier playing Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4. As two o’clock approached, there was a lot if milling around on stage, with players coming and going and the audience getting restless. Finally, after about 15 minutes, someone came out on stage and gave one of those “due to circumstances beyond our control” announcements to the effect that the Mozart would not be performed and, since the Glière symphony required a much larger orchestra, some of the players had not arrived yet. I assured a woman sitting next to me that, since the uncut Glière Third is longer than some Bruckner and Mahler symphonies, we would still come close to getting our money’s worth. Finally, all the players showed up and Neeme Järvi came on stage and led what I thought was a restrained performance of the symphony (he was recovering from a heart attack), and I thought the sound of the hall too dry for my taste, if not as dry as that of the Academy of Music. At the time, the place was still a work in progress and I don’t know what it sounds like nowadays. As for Zehetmeier, he later explained that he didn’t realize that the Friday concert was a matinee until it was too late!

Stokowski said that, early in his Philadelphia career, he had the opportunity to discuss the symphony with Glière and the composer (supposedly) agreed that his symphony could be performed with certain cuts. He also met Glière when he visited the Soviet Union in 1931. In 1940 he recorded the symphony with the Philadelphia Orchestra. A complete, uncut “Ilya Murometz” runs between, say, 75 and 78 minutes. Stokowski’s 1940 recording runs 46 minutes. It’s hard to believe that the cuts were all Glière’s idea. In later years, Stokowski favored a more heavily cut edition that runs 38 minutes on his recording with the Houston Symphony Orchestra and about a minute longer on this Chicago broadcast. One addition to the shorter edition is that, whereas the Philadelphia recording fades out quietly, on the Houston and Chicago recordings, he uses Glière’s solemn, louder ending, which applies a more decisive period to the piece. Each conductor who has cut the piece for a recording has done his own cuts. In ascending order of completeness, the ones I’ve heard are the two later Stokowskis, the Rachmilovich, Stokowski/Philadelphia, Fricsay, the two Ormandys, Talmi, Rakhlin, and the uncut ones of Botstein, Downes, Johanos, Scherchen, and Farberman—that last one, thanks to some sight-reading tempos, stretching out beyond 90 minutes; he conducts as if he relishes every note in the score. Now there’s a spread: 38 minutes to 92 minutes! What you won’t get on Stokowski’s Chicago performance are the high frequencies; what you won’t get on the Houston performance is the sheer massive power of the Chicago brasses and some interesting wind details. On the Houston recording, you can hear Stokowski’s eccentric placement of the orchestra, with all the winds and brass on stage left and the violins, violas, and cellos taking up most of what space remains, with the basses lining the back of the stage. You won’t hear that on the CSO performance, which is a mono recording. Both, like his 1940 effort in Philadelphia, are animated, intense performances. I suppose an uncut Stokowski “Ilya Murometz” was too much to hope for.

Obviously, this pair of CDs preserves two important concerts in the CSO’s history—the first guest appearances by one of the 20th century’s most import maestros. Stokowski recorded most of this music earlier and/or later, but there seems to have been good chemistry between him and the CSO—several of the players were alumni of his All-American Orchestra.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 34:4 (Mar/Apr 2011) of Fanfare Magazine.