This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

Horenstein is masterful in this brilliant, previous unreleased 1960 Vienna Mahler 9

"This performance is the Horenstein Mahler Ninth to own"

- Fanfare

Conductor Jascha Horenstein has long been regarded as one of the finest exponents of the music of Gustav Mahler. His 1952 studio recording of the Ninth Symphony was the first such recording to be commercially released (the 1938 Walter was partly or entirely live; a 1950 studio effort by Scherchen only appeared long after it was recorded). A small handful of other recordings, made between the mid-1950s and the late sixties and generally live, have appeared over the years, but never this particular rendition from the Vienna Festival of 1960 which, over three weeks, celebrated Mahler's centenary. The conductor's cousin, Misha Horenstein, who has once again generously supplied the source recording for this release, writes eloquently on the background to this performance on our website (see above).

Technically the remastering proved trickier than first hearing suggested it might. Although there were no major or obvious flaws beyond one or two instances of tape dropout, microphone positioning, coupled with a mono sound, made for a somewhat uncomfortable listen during louder passages, with a mid-range stridence in the upper strings that took some effort to tame without sacrificing the direct energy and vivacity of the central movements.

This is a mono recording, but the aforementioned issues aside, it's now a very good one - especially given Pristine's Ambient Stereo treatment, which I strongly recommend here. The orchestral sound is especially clear, full, direct and vivid.

Happily the audience generally saved their coughing, shuffling and throat-clearing for lengthy gaps between movements which, in order to fit the music to CD duration, have been edited down significantly. The result is one of the great Ninth performances, offered for the first time, and in superb sound quality.

Andrew Rose

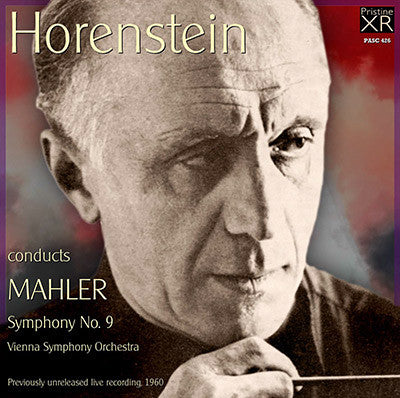

MAHLER Symphony No. 9

Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Jascha Horenstein, conductor

Recorded 22 June 1960, Konzerthaus, Vienna

Closing concert of the 1960 Vienna Festival «Wiener Festwochen»

Recording from the archive of Misha Horenstein

First publication of this recording

This recording documents the closing concert of the 1960 edition of the Vienna Festival «Wiener Festwochen», part of which was devoted to a celebration of the centenary of Mahler’s birth. This included performances of his music, lectures, publications and an exhibition called “Mahler and his Time,” and was the first occasion since the Second World War that Vienna celebrated the life and work of one of its most illustrious citizens.

Besides Horenstein, other conductors appearing at the festival included Bruno Walter in Mahler’s Fourth; Herbert von Karajan, who presented “Das Lied von der Erde” with the Vienna Philharmonic; Josef Keilberth, who conducted Mahler’s Eighth; Klemperer and the Philharmonia orchestra in a complete cycle of all the Beethoven symphonies, and Karl Böhm, who led a concert performance of Alban Berg’s opera “Lulu”. In this lineup, Horenstein was not the star attraction.

The choice of the Mahler’s Ninth Symphony to end the three-week long festival was not without controversy. Erwin Ratz, President of the International Gustav Mahler Society, complained that “because of its extraordinarily pessimistic and sombre character”, the Ninth was not a suitable work for a final celebratory concert. His preference was for the Seventh Symphony, a much more suitable and appropriate choice but also motivated by self-interest, since his organization had recently published the score as the first volume in the critical edition of Mahler’s complete works. Ratz’s suggestion had been overruled by higher powers and in a letter to Horenstein he appealed for support:

“I am making this suggestion to you because I can already predict how people will react to the Ninth. To my great dismay I have also had to experience this not only in Vienna but also in Amsterdam and other places. It is, above all, in the ironic and bitter nature of the two middle movements that people see their own reflection and to which they then react so bitterly."[1]

Ratz was right. Unlike in London and New York, Mahler's music in general and the Ninth Symphony in particular did not find a receptive home among peers and audiences in Vienna during the early 1960s. It had to wait until Leonard Bernstein persuaded them a few years later that Mahler was a composer worthy of attention.

Horenstein’s concert was given in the Konzerthaus auditorium by the same orchestra and in the same venue that hosted his professional debut as a conductor thirty-eight years previously, when the work played was Mahler’s First symphony. Although the concert in 1960 was Horenstein’s first appearance on a Viennese stage since before the rise of Hitler, he had worked extensively in the Austrian capital, and with the same orchestra, as a recording artist for Vox Records during the 1950s. These included his now celebrated account of Mahler’s Ninth on that label, which for many years served as the standard by which all subsequent recordings were judged.

Although raised and educated in Vienna, Horenstein never managed to convince the Viennese public to embrace him with the same enthusiasm they bestowed on some of his colleagues, and this June 1960 appearance was no exception. Part of the reason was that the orchestra did not warm to him personally or as a conductor, while for the Viennese public Mahler’s music was still under the cloud of anti-Semitic rejection.

Reliable documentation can back up this claim. Witnesses who attended both the rehearsals and the performance have testified that Horenstein had to “coax” the music out of “an unwilling and hostile orchestra” that treated the work with scorn and derision. "Immer-an-der-Wand-lang / Immer-an-der Wand-lang", they intoned, mocking the opening bars of the Scherzo movement, and did their best to sabotage the proceedings by “intentionally inaccurate playing.” Horenstein himself found the going rough and was “stressed out” during the rehearsal breaks.[2]

Under these circumstances, it is amazing that the result here is as good as it is. Horenstein’s absolute identification with the Mahler idiom, his unerring instinct for proportion and organization, his perfectly timed climaxes resulting from the music’s natural flow, are here as evident as in any of his other five preserved recordings of this momentous and monumental work.

[1] Cambridge Companion to Mahler, p.221

[2] Hans Wollschläger, Moments musicaux - Tage mit T.W.Adorno, Wallstein Verlag, 2005

Fanfare Review

The finest live performance of the Mahler Ninth that I’ve ever heard.

This is the finest live performance of the Mahler Ninth that I’ve ever heard. I’ve been fortunate to hear two excellent renditions in concert, one by Christoph von Dohnányi and the Cleveland Orchestra, the other by Jacques Lacombe and a greatly augmented New Jersey Symphony. Horenstein’s surpasses them in understanding and dramatic tension. The conductor’s cousin Misha Horenstein writes that this symphony in 1960 had not yet been accepted by the Viennese players and public, and that the orchestra gave the conductor a rough time in rehearsals. Horenstein must have worked some magic at the concert, for the playing is stupendous. This was the final concert of the 1960 Vienna Festival, which included a tribute to Mahler on his centenary. It was Horenstein’s first appearance on a Viennese stage since before the Second World War, despite having recorded extensively in Vienna for Vox in the 1950s. I believe the conductor had a very personal message for his audience in programming this symphony on his return. Never in my experience has Mahler’s bitterness at unreasoning hatred—namely the anti-Semitism which drove him from his Viennese post a year prior to his starting work on this symphony—been better expressed than by Horenstein, particularly in the middle two movements. I’m sure Horenstein identified with this personally. Leonard Bernstein wrote in his Norton Lectures that Mahler had foretold all the disasters of the 20th century in this symphony. I’ve always found this to be a rather grand pronouncement, but upon hearing the present performance, I can believe it.

Horenstein regards the Ninth as an intensely modern work, conducting it with sharp accents and shrieking orchestral colors. Listeners familiar with his superb Arnold Schoenberg LP for Vox will not be surprised at this predilection. Horenstein’s tempos, slightly on the brisk side throughout, are beautifully integrated to show the work’s structure. The struggles in rehearsal probably contributed to the overwhelming atmosphere of tension in the performance. The opening movement vacillates between death as a noble leave taking and the torturous ache of Yeats’s “foul rag and bone shop of the heart.” At times the composer needs to catch his breath from all that pressure. One wonders if this music also is about the European humanistic culture Mahler may have felt was dying with him. Horenstein is one of the few conductors to observe Mahler’s instruction “very rough” in the next movement. Here the wicked treatment of the Ländlers demonstrates how a folk culture can develop a collective neurosis, as in Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. This cynical take on a traditional form parallels what Ravel would do later in La valse. The third movement is an intensely bitter experience, a nightmare of mockery. Even a section of nature poetry, recalling the composer’s “Blumine,” has fatal overtones. The last movement reminds us of Mahler’s admiration for the pathbreaking slow finale of Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique” Symphony. This is like the death of the hero in epic poetry, the operatic death scene Mahler never wrote—with hints of Siegfried’s Funeral Music. We hear Horenstein stamping on the podium along with a phrasing he wants. A slight disagreement over an entrance in the strings near the end barely mars the total experience.

Andrew Rose has taken a monaural master tape that clearly had some problems and contrived sound that is full, warm, and well balanced, with an excellent dynamic range. Heard in Pristine’s ambient stereo, the sonic perspective is especially luminous. My favorite recording of the Ninth in true stereo is the 1969 Philips version by Bernard Haitink. Among digital accounts, I like Kurt Sanderling with the Philharmonia and Lorin Maazel in Vienna. The present Horenstein concert now is one of the essential Ninths in my collection, a riveting and harrowing experience you will not easily forget. If Mahler was a prophet, then the Horenstein recording is his Talmudic exegesis.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:5 (May/June 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

Horenstein made the first studio recording of Mahler’s Ninth with this same orchestra in 1952 for Vox (the earlier Bruno Walter recording with the VPO was either mostly or entirely live). That recording has long been admired by collectors and critics, but all have noted its rather dry sound and somewhat scrappy orchestral playing. That has been supplemented by two live performances before this one: one with the London Symphony and one with the French National Radio. A 1966 LSO performance was first issued on Music & Arts. BBC Legends “officially” released a 1966 LSO performance, which I had always assumed was the same as the Music & Arts version but with better sound (Christopher Abbott reviewed it in Fanfare 25:1). In fact, a close listening to both in preparation for this review shows that they are not the same performance. Coughs in the audience differ, the audience applauds after the first movement on the BBC edition but not the M& A, and the finale is notably slower on the M& A. Since M& A does not provide a date any more specific than “1966,” we cannot be certain of its provenance. Additionally, there is a 1969 American Symphony Orchestra performance on Music & Arts that has not been reviewed in Fanfare, and that is not as well focused and purposeful as any of the earlier ones. A look through the Fanfare Archive will bring you a number of reviews of different Horenstein performances of this work.

The general favorite among not only Fanfare reviewers but many collectors has been the BBC Legends stereo release of the September 15, 1966 LSO performance at the Royal Albert Hall from a Proms concert. Given that this is monaural (though Pristine’s XR Ambient Stereo process gives a very nice sense of air and space around the orchestra) and given that the Vienna Symphony Orchestra is not the premier orchestra in Vienna, one might expect the BBC Legends release to continue to be preferred. It is not so simple. Both are wonderful performances, and Pristine’s sound is excellent. It is reported by Misha Horenstein (the conductor’s cousin) on the Pristine web site that the Vienna orchestra was hostile both to Mahler’s music and to Horenstein at this time, but you would never know it. They play with commitment and intensity throughout.

Horenstein’s Mahler has always inhabited a special world between the extremes of other conductors. Not as overtly emotional and intense as Bernstein, nor as gentle and warm as Walter, nor as granitic as Klemperer, but encompassing all of those elements in balance, Horenstein was without question one of the great Mahler conductors of the 20th century. His affinity for the style led him to demand, and get, a tasteful use of portamento from his string players (wonderfully effective in his studio LSO recording of the Third Symphony’s finale), so that even while his rhythms are always taut and firmly sprung, there is lyrical beauty to be heard throughout. The inner movements here are wonderfully grotesque, and potent at slightly faster tempos than the LSO performance. The long final Adagio is, as always with Horenstein, deeply moving without becoming maudlin. Horenstein’s ability to incorporate in a balanced way all of the extremes in Mahler’s music, to give shape to the overall without slighting the drama of the moment, was unique. It is that sense of proportion that is a main hallmark of his Mahler performances.

If you already own the BBC Legends performance this is probably an extravagance unless you are (as I am) a committed fan and collector of this conductor. But if you don’t, one could easily make the case that this performance is the Horenstein Mahler Ninth to own. It has a slight edge over the BBC in firmness, without giving up any of the music’s beauty. Once again, Pristine has performed a real service.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:4 (Mar/Apr 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.