This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

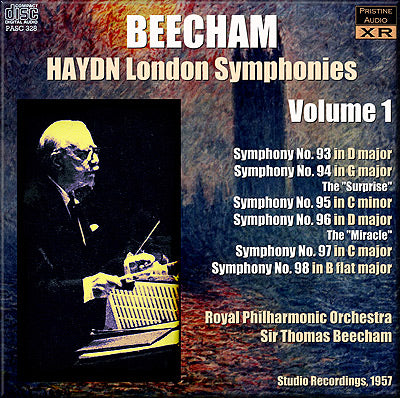

Beecham's supreme musicality exemplified in Haydn's symphonic masterworks

First six 'London' symphonies in superb new 32-bit XR-remastered transfers

Fanfare Review

This is the issue to get ... we get a truer picture of the Royal Philharmonic and of Beecham’s Haydn

What, again? EMI reissued these recordings on CD in 1992, in 2004, and in 2011. We’ve been talking about escaping the “Papa Haydn” syndrome for half a century, and these are the performances we’ve been trying to escape. In Fanfare 28:3, I damned them as “overbearing … stolid … square … affected, more Beecham than Haydn … little sense of spontaneity or joy.” In 35: 2, Richard A. Kaplan, reviewing a 34-CD Beecham set, found these Haydn symphonies “inappropriately weighty, even pompous.” Kaplan’s description of Beecham’s Mozart (“alternately stodgy and quaint”) fits my view of his Haydn even more closely. I’ve listened to only the first CD of the first set (Symphonies Nos. 93, 94, and 95), as that’s what arrived in the mail, but I’ve known these recordings from time immemorial. A second disc is supposedly on its way; if it brings any surprises, I’ll get back to you.

The second set arrived complete. The opening Vivace assai of No. 99 in E♭ is played slowly, depriving it of all vigor and sparkle; the following Adagio is softened and sentimentalized. Beecham’s Minuet is a prime example of the Papa Haydn syndrome, powdered wig and all; the carefully isolated chords have no force of attack, and the Trio is unbearably sweet. The Vivace finale tiptoes along at a very moderate pace. One of Haydn’s most dynamic, potent symphonies has been reduced to a series of charming effects. I could go on and on, but to what point? With such performances the norm in the first half of the 20th century, it’s no wonder that Haydn was considered a minor composer. Beecham (1879–1961) was locked into that time; in 1958 he still used error-ridden scores from an earlier era, ignoring all of Robbins Landon’s corrections as well as most repeats. By this time, Hermann Scherchen’s recordings and many on the Haydn Society label had demonstrated how vital Haydn’s symphonies are. There are a few movements that go well in Beecham’s performances, notably the opening Allegro of No. 104, the “London” Symphony.

If you must have these recordings, however, this is the issue to get. The performances in the first set (Symphonies 93–98) have suffered great indignities from EMI’s executives and engineers. First, this English orchestra traveled to Paris in October 1957 to record five of these six symphonies at Salle Wigram, perhaps the only major recording site not equipped for stereo at the time. All of EMI’s reissues have been in an electronic stereo version. Pristine’s Andrew Rose has restored true mono, and then added his “far more subtle Ambient Effect” as an option, heard on the review copies. The second set is in stereo. Rose also has rectified a number of pitch irregularities that have plagued previous issues. The result is that we get a truer picture of the Royal Philharmonic and of Beecham’s Haydn. Which engenders a disturbing paradox: Now that the orchestra can be heard properly, all the problems that Kaplan and I complain about stand out even more clearly.

James H. North

James H. North

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:1 (Sept/Oct 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.