This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

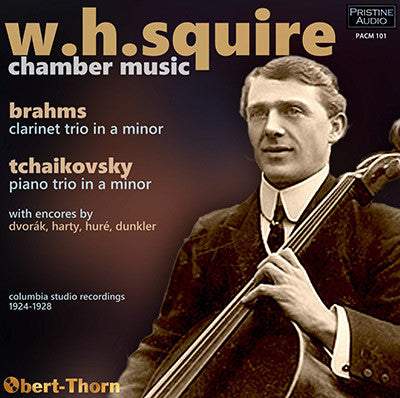

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

W. H. Squire's brilliant chamber music brought back to life by Mark Obert-Thorn

"A splendid virtuoso and also one of the wisest and most broadminded of men" - Hamilton Harty

During a recording career that stretched from the late 1890s to the

early 1930s, British cellist William Henry Squire (1871-1963) set down

many sides of short encore pieces and two cello concertos (the latter

featured on Pristine’s earlier release devoted to Squire, PASC 393).

Although he, along with violinist Arthur Catterall and pianist William

Murdoch, made a series of acoustic recordings of movements from chamber

works usually abridged to a single side, Squire only participated in

three complete chamber music recordings: Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio

(on Pristine PACM 073), and the two A minor trios presented here.

It

is remarkable that at a time during the acoustic recording era when few

chamber works were available complete on disc, Columbia would have

chosen to record Brahms’ less well-known Clarinet Trio. The clarinetist

is Haydn Paul Draper, nephew and pupil of the more well-known Charles

Draper (who also recorded chamber music for Columbia around the same

time). Hamilton Harty (not yet “Sir” – his knighthood would come the

following year) is the pianist, as he was on many of Squire’s solo discs

in the acoustic era. Brahms had declared his composing days at an end

with his G major String Quintet in 1890; but hearing clarinetist Richard

Mühlfeld inspired him to write this trio the following year, along with

his Op. 115 Clarinet Quintet.

Tchaikovsky was initially

reluctant to write a traditional piano trio, feeling that the sound of

the piano did not mesh well with the violin and cello. However, the

death of his close friend, the pianist/composer/conductor Nikolai

Rubinstein in 1881 prompted his Op. 50, his only work with this

combination of instruments. Squire here is joined by British violinist

Arthur Catterall and Australian pianist William Murdoch, frequent

chamber partners of his both in concert and on disc. The recording is

not quite complete; the Finale section of the second movement was cut to

about half its length, probably to avoid going to an additional odd

side. Based on the ample reverberation to be heard, the session may

have been held in Wigmore Hall, as was the Beethoven “Archduke” with

Sammons, Squire and Murdoch from a few days earlier. However, the

original engineering here seems to be more distant and recorded at a

lower level.

Concluding our program are four cello encores of the

type for which Squire was most famous on disc. Squire’s frequent

collaborator as conductor and accompanist, Harty, is heard here as a

composer. French organist and composer Jean Huré (1877-1930) wrote his

“Air” to be accompanied by either piano or organ, and Squire recorded it

both ways, the first acoustically and the second, heard here,

electrically.

The sources for the transfers were mainly American

Columbia discs – a “New Process” set for the Brahms, and “Viva-Tonal”

pressings for the Tchaikovsky, Harty and Huré works. The Dvǒrák and

Dunkler pieces came from an Australian Columbia disc.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

BRAHMS Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. 114 (acoustic recording)

H. P. Draper (clarinet) ∙ Hamilton Harty (piano)Recorded 21 October 1924 in London

Matrix nos.: AX 692-1, 693-2, 694-1, 695-1, 696-1 & 697-1

First issued on Columbia L 1609/11 -

TCHAIKOVSKY Piano Trio in A Minor, Op 50, “To the Memory of a Great Artist”

Arthur Catterall (violin) ∙ William Murdoch (piano)Recorded 23 December 1926 in London

Matrix nos.: WRAX 2311-2, 2312-2, 2313-1, 2314-2, 2315-2, 2316-2, 2317-1, 2318-1, 2319-1, 2320-2, 2321-3, 2322-1

First issued on Columbia L 1942/7 -

DVǑRÁK (arr. Grünfeld) Songs my mother taught me, Op. 54, No. 4 (from Gypsy Songs)

With piano accompaniment

Recorded March, 1928 in London

Matrix no.: WA 7085. First issued on Columbia D 1620 -

HARTY Scherzo, Op. 8

With piano accompaniment

Recorded 13 April 1927 in London

Matrix no.: WAX 2571-2. First issued on Columbia L 2115 -

HURÉ Air

George Thomas Pattman (organ)Recorded 3 October 1928 in the St. John’s Wood Synagogue

Matrix no.: WAX 4128-1. Issued on American Columbia 50214-D -

DUNKLER La fileuse (The spinning wheel), Op. 15

With piano accompaniment

Recorded March, 1928 in London

Matrix no.: WA 7088

Issued on Australian Columbia 03611

W. H. Squire, cello

Brahms Clarinet Trio

Among Brahms’ last and most mature works

are four in which the clarinet is used, with remarkable facility, and

with a perfect perception of its powers. His employment of the

instrument in this late chamber music was largely influenced by' hearing

a very fine clarinet player, Mühlfeld. The work is recorded uncut.

First Movement.

Allegro

(quick).—Very characteristic of Brahms are both the leading themes used

in this movement. Their arpeggio nature is a favourite device of the

composer, and the first conforms even more closely to one of his habits

of mind in building tunes, by commencing with the four notes of the

key-chord. In order to keep the tonal balance, the ’cello frequently

plays in its high register, the piano filling up the middle of the

compass. The second main theme begins at the top of page 5, on the

’cello, and is in the major key. The first theme, when it returns after

the development (in the ’cello) is considerably altered. In particular,

there is an increase of the rushing scalic work of which we had a taste

on the second page, just before the entry of the second subject. The

quick leaping figures of this movement are finely contrasted with the

more broadly moving yet still agile even-beat stepping (cf.. e.g., pages

12 and 13). A passage of scales and arpeggios, over piano chords,

brings the movement to an end.

Second Movement,

Adagio

(slow).—Clarinet (answered by ’cello) has a descending- and-mounting

theme, in leisurely stride, varied (top of page 15) by another which the

clarinet has first, in a minor key. The treatment is free, the dialogue

moving serene and eloquent, unhurried yet unflagging. On page 16 the

clarinet has a version of the first theme in which its main melody notes

are emphasised, the smaller, more quickly-moving notes being omitted.

(The ’cello’s plucked notes here are not quite of the sweetest; and

throughout its highest notes have a trace of whine). The leading theme

is heard again on page 17, bottom line, upon the ’cello.

Third Movement.

Andantino

grazioso {slowish, gracefully).—This is called “ scherzo ” on the

label, but it is more like the older minuet. (Compare its feeling with

that of the Mozart B flat Quartet, noticed elsewhere.) It is slight, and

scarcely of interest equal to that of the other movements. A point of

interest is the long sweep of the first tune—an extended melody. After

this has been repeated by the piano, a minor-key section ensues,

followed by a partial repetition of the first portion of the movement.

Then comes a new section, with the clarinet moving in sweeping

arpeggios. A return of the first theme (’cello) brings the movement to

an end.

Fourth Movement.

Allegro (quick).—The time is

given as 2/4 (6/8)—two in a bar, but the beats sometimes divided into

two parts, sometimes into three. This makes for that diversity of rhythm

that Brahms was so fond of. The leaping tune that begins (in the

’cello) comes very often, in some shape or other. So does the

five-semiquaver figure that the piano has in the second line. (Already

we have our alternation of beat-division, it will be noticed.) At the

seventeenth bar comes a tune, the complement of the first—leading up (at

the two bars of slower notes, bottom of page 31) to the second chief

theme, distinguished by its being partly two-in-a-bar and partly in

three. Its second half (bottom of page 32) is given by piano alone.

After only eight bars of this, the first chief tune returns (piano), its

complementary portion being delayed by a little development and by a

kind of “false start” (bottom of page 34), The piano, as before, has

this portion to itself. Follows a repetition of the alternated

two-and-three-beat section, in its two parts (second this time given to

clarinet and ’cello), and a coda wherein some joyous arpeggios round off

the movement.

The only fault I find in the playing is that the

’cello is sometimes a thought too strong for the reed instrument (most

beautifully played); and that the piano tone, though pretty good

(sometimes notably so) fails on occasion to give full sonority. If any

are a little surprised to see Mr. Harty in the ranks of pianists, it may

be recalled that before becoming known as a conductor he was one of the

finest accompanists we had. His sensitive playing here is in the

highest degree effective, and the limitation spoken of, I am sure, is

purely that of the piano, not of the player.

K. K., The Gramophone, February 1925

Tchaikovsky Piano Trio

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Trio in A minor “To

the Memory of a Great Artist” played by Arthur Catterall, W, H Squire

and William Murdoch L.1942-47 (12in., £1 I9s., in an album). It is good

that this work has been recorded in its entirety. The Theme and

Variations out of it, on one record, was among the precious early

chamber music records of pre-electric days, but that sort of thing is

not good enough to-day: and therefore the same three artists have played

the whole work on six records, very much to the credit of Columbia. The

performance is good though it never breathes quite so deeply as was

intended by the composer. The best playing is to be found in the

variations, which also are more in chamber music style than the first

movement, where a dramatic line is maintained not unlike that of the

symphonies. (It is queer that Tchaikovsky in his operas is lyric and in

the symphonies and for instance this trio is dramatic to a great extent.

The operas, by the way, are not out of repertory to-day, as the analyst

of the album will have it, Onegin and even Pique Dame being in steady

demand on the Continent.) Nevertheless it is an extremely enjoyable

performance which is sure to be welcomed by the many lovers of this fine

work. There is no need for me to add anything in the way of analysis,

since this is well done in the album itself

C. J., The Gramophone, July 1928

Fanfare Review

Recommended to collectors of historic recordings - the leading British cellist of his generation

William Henry Squire (1871–1963) was the leading British cellist of his generation; despite his longevity, however, his recording career seems to have lasted only into the early 1930s. In addition to the works offered here, he also recorded concertos of Saint-Saëns and Elgar, Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio (all also available from Pristine), and numerous shorter works such as the four encores included on this CD. The recordings here were all made between 1924 and 1928 for English Columbia, and the two major works were first recordings.

Squire’s collaborators were all well known as well. Haydn Draper was the nephew of the famous clarinetist Charles Draper, who recorded both the Mozart and Brahms Quintets with the Léner Quartet; Arthur Catterall and the Australian pianist William Murdoch have both fallen into obscurity, but were leading recording artists of their day. Hamilton Harty, best remembered as a conductor, was a triple threat, and is documented here in his other two roles, those of pianist and composer. He was knighted the year after this recording was made.

Despite the able ministrations of producer Mark Obert-Thorn, there’s no mistaking the acoustic origin of the 1924 Brahms recording; the sound is boxy, with a bit of an edge to Squire’s tone. The balance favors the cello, which probably was closer to the recording horn than the other two instruments. Nevertheless, one can tell that Draper had a pure sound—the ascendancy of Reginald Kell, who was to change English clarinet playing, for better or worse, for three generations, was still in the future—and that Harty acquits himself well. The interpretation is rather mainstream, but the tempo of the last movement is somewhat unbending, perhaps partially owing to the four-and-a-half minute limitation of the 78-rpm side.

The sound is much better in the 1928 recording of the Tchaikovsky Trio, which was extravagantly spread over 12 sides—and that with a sizeable cut in the finale. There is, for the time, an unusual amount of reverberation in this recording; Obert-Thorn says in his note that this trio was recorded at a lower level, which might explain the atypical amount of surface noise that remains in the transfer. The performance is more free-wheeling than that of the Brahms, with plastic tempos and lots of portamento from both string players. Murdoch plays his share of wrong notes; of course, editing of recordings was impossible in those days.

The four encores document a kind of cello playing not heard anymore, with frequent, generous slides. Here, far more clearly than in the sonically compromised Brahms, or even in the Tchaikovsky, where the violin predominates, Squire displays a fine tone and a tasteful vibrato. The Harty and Dunkler pieces also show that he had a healthy technique.

Given the limitations of the originals, Obert-Thorn’s transfers are exemplary; the side joins are undetectable even if you know where they are, and aside from the Brahms, the sound is as natural as you could hope for, considering the nearly 90-year-old originals. Now perhaps Pristine can be persuaded to devote a CD or two to the all-but-forgotten Catterall, who recorded two concertos and four sonatas for Columbia in the 1920s. Recommended to collectors of historic recordings. Richard A. Kaplan