This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

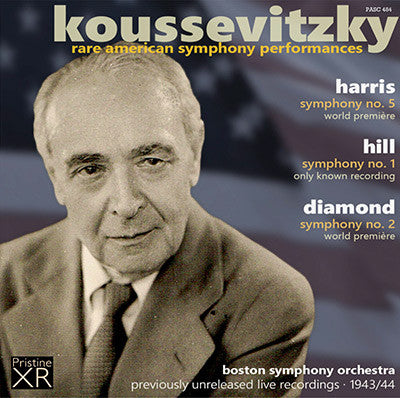

- Cover Art

- Original Programme Notes

Three previously unissued American symphonies - including two world premières

"Vivid

performances in clear historic sound that captures the tragedy, up-beat

excitement and sheer valour of the times in which they were performed"

- MusicWeb International

All three recordings on this release are truly historic documents, not only of the works and performances concerned, but of Serge Koussevitzky and the BSO's tremendous work in promoting and commissioning new works. Edward Burlingame Hill's Symphony No. 1 was premièred by Koussevitzky in 1928 (to be followed by two more symphonies) - this was its final BSO performance of nine.

The Harris and Diamond symphonies here are both premières (to be technically correct they had received their first performances the previous day in Friday matinee concerts, duplicated the evening after from which these recordings derived). Resurrecting these previously unheard acetate off-air recordings has been a monumental task, with numerous significant technical hurdles to be overcome, including massive pitch issues particularly with the Harris and Hill.

Surface noise was a constant and at times chronic problem, and unfortunately some peak distortion remains, particularly in the finale of the Diamond. The latter also required two minor patches to cover side changes, which I hope I have rendered undetectable. Cross-talk and other radio interference have been removed, though the frequency and dynamic limitations of AM radio remain.

That said, the finished result of my efforts will prove, I hope, entirely enjoyable. The Harris and Diamond symphonies may be familiar to some; however this appears to be the only known recording of Hill's Symphony No.1.

Andrew Rose- ROY HARRIS Symphony No. 5 (1942) - WORLD PREMIERE

- EDWARD BURLINGAME HILL Symphony No. 1 in B flat, Op. 34 (1927) - ONLY KNOWN RECORDING

Recorded live at Symphony Hall, Boston, 27 February 1943

- DAVID DIAMOND Symphony No. 2 (1943) - WORLD PREMIERE

Recorded live at Symphony Hall, Boston, 14 October 1944

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Serge Koussevitzky, conductor

ORIGINAL CONCERT PROGRAMME NOTES

Programme notes for the concerts of 26 and 27 February 1943:

SYMPHONY in B-flat major, No. 1, Op. 34 (Composed in 1927)

By Edward Burlingame Hill

Born in Boston, Mass., September 9, 1872

This symphony was composed in 1927 and first performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Boston, on March 30, 1928. The symphony has also been performed March 22, 1929, and December 21, 1934.

The orchestration includes four flutes and two piccolos, two oboes and English horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contra-bassoon, six horns, four trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle, tambourine, glockenspiel, piano and strings. The score is dedicated to Serge Koussevitzky.

The First Symphony, so Mr. Hill explains, “has no descriptive basis, hints at no dramatic conflict or spiritual crisis. It attempts merely to develop musical ideas.

“After three measures of introduction, the principal theme is announced by the horns. After the usual transition, the second theme, given mainly to strings, appears in the mediant major. The conclusion theme emphasizes the same tonality. The development is based upon the principal subject, and the conclusion theme up to the passage which leads to the restatement. The'second theme is then given more orchestral emphasis. The coda is brief, and the end quiet.

“In the slow movement, a section in E-flat minor gives way to an episode in the relative major. After some development, the first section returns somewhat varied, and closes with an allusion to the central episode.

“The finale is virtually in rondo form. The first theme is rhythmical; the second lyrical. Towards the close of the movement, the second theme is given to the brass, leading to a brief coda.”

Mr. Hill has composed three symphonies. The Second, in C major, was introduced at these concerts February 27, 1931, and the Third, in G major, December 3, 1937. The Sinfonietta, in one movement, was played March 10, 1933, and the String Sinfonietta April 17, 1936.

By David Diamond

MusicWeb International Review

Koussevitzky was a boon to American composers of the first half of the twentieth century and this disc adduces three substantial pieces of evidence bearing out the assertion

For such a diminutive outfit, Pristine are astonishingly productive

in terms of quality and quantity. Add to this, that, to their credit

they will not allow slight blemishes - even ones that cannot be 'healed'

to prevent the issue of valuable and enjoyable rare material. They have

also had the integrity to reissue their recordings where improved originals have surfaced after initial release.

Pristine's foray into the historical recorded legacy music of America

from the first half of the twentieth century is expansive. It takes in

the prodigious work of Howard Hanson as composer and as conductor (review review review review) as well as a blistering account of Hanson's opera Merry Mount (review), a selection of rarities from 78s including the Piston Second Symphony (review) and Piston's Third as conducted by Koussevitzky and recorded in 1948. Add to these two very special Harl Macdonald discs (review review review).

Now Andrew Rose - who is Pristine Audio - adds an impeccably

fully-loaded CD of 1940s vintage recordings of live performances, all in

his trademark XR re-mastering. These three previously unissued mono

inscriptions of rare American symphonies are in historic sound

originating in the AM radio signal of the 1940s. They blossom under

Pristine's care. All that punctilious surgery on clicks, cracks,

distortion and ambience must have been time-consuming. It was worth the

effort.

Two of the symphonies (Harris and Diamond - products of

war-time) are heard in their premieres so have documentary standing

quite apart from their intrinsic musical values and pleasures.

Koussevitzky was a boon to American composers of the first half of the

twentieth century and this disc adduces three substantial pieces of

evidence bearing out the assertion.

Koussevitzky had a belief

in Harris the symphonist in which he was not alone among North America's

great conductors and orchestras. His practical commitment to the cause

can be traced back to his 1934 recording of Harris's First Symphony

1933: Pearl GEMM CD 9492 and before that on LP Columbia Masterworks

ML5095 from the original 78s. Then, so far as record collector

enthusiasts are concerned, there was the standard-bearer for Harris

during his years of neglect: Koussevitzky's 1939 recording of the Third

Symphony (Great Conductors of the 20th Century

on EMI CZS 5 75118-2 originally released on RCA LCT-1153 circa 1955

from RCA 78s). The latter also included Koussevitzky and the Bostonians

in Sibelius 5 and Pohjola's Daughter. This was my initiation

into the world of Roy Harris via RCA Victrola VIC 1047 in their

Sovereign LP series. I bought the Victrola LP secondhand as a student

from a small record shop in Bristol not far from Gloucester Road. You

can add to this roll-call the Harris Sixth Symphony which was issued by

AS Disc on AS 563: Boston Symphony Hall, 15 April 1944.

The

Harris has a vital energising kick and those eight horns belting out in

unison only emphasise this. The first movement stands as one of Harris's

most heroic and determined inspirations. Koussevitzky does nothing to

mask the gallantry; rather he presses and pushes forward. The slow

middle Chorale growls and rumbles with tragedy; there's a cough

at one point but it is soon gone. The pressurised writing here reminded

me several times of RVW 4. The final Fugue is not a typical

rigid fugue, so worry not. Harris suffuses that movement with nervy

electricity and pliantly dancing optimism. Some of this can be felt also

in the Fourth Symphony's purely instrumental movements. Fast-stabbing

attack characterises the movement as does the sound of massed violins in

high tension neon cantabile. Yes, the sound crumbles at the

periphery in the violin 'songs' but never so much that you cannot follow

and revel in this very special music-making. This disc presents Harris 5

in its original version. Harris continued to make revisions to the

work. There have been two modern recordings of the Fifth Symphony (Naxos and First Edition). This Pristine one occupies a position in relation to them rather similar to that of the 1938 Bruno Walter Mahler Ninth to the market-leader digital Mahler 9s; see also here. The same can be said of this Diamond Second Symphony.

I wonder if anyone out there has the William Steinberg/Pittsburgh

Symphony LP of the Fifth. It's on Pittsburgh Festival of Contemporary

Music PFCM-CB-165. I would very much like to hear it.

It's such

a pity that, after the Sixth, Harris symphony premieres seemed to move

away from Boston and Koussevitzky. Harris dedicated the Fifth to "the

heroic and freedom-loving people of our great Ally, the Union of Soviet

Socialist Republics". He reportedly suffered during the McCarthy era for

his pro-Soviet stance; but then so did Copland. Even so, Ormandy in

1956 recorded the Seventh Symphony (Albany TROY 256) and it is nothing

less than a glory of recorded sound. The Seventh stands as the pinnacle

of Harris' achievement, even more so than the multiply-recorded Third.

There has been well-merited praise for the music of Edward Burlingame Hill not least for the Fourth Symphony (Bridge) and the Violin Concerto (West Hill). In fact the 'trigger' for me was Bernstein's venerable recording of Hill's orchestral Prelude - a lush impressionistic work seemingly influenced by Daphnis and by Spring Fire.

The lushly passion-saturated three-movement First Symphony is fresh and

has a Franckian propulsion. The finale has some swooning Baxian writing

too; no wonder that the same forces had premiered Bax's Second Symphony

only two years after this work was premiered there. The Hill is a

winning work and its success lies in the Boston/Koussevitzky factor. I

have been disparaging of Koussevitzky's much vaunted commercially

recorded Sibelius

but these live performances are quite another matter. There's the

occasional dim and distant cough and applause at the end but little to

detract.

The four-movement David Diamond Second Symphony surges

forward with luxuriously Barber-like lungs - elongated singing lines

and great emotional concentration. Its first movement is, after all, an Adagio funebre. The following Allegro vivo has the fierce tempestuous pulse of Ulysses Kay's contemporaneous overture New Horizons

and at about 1:20 Diamond introduces a euphoria that tempers the

preceding grittily embattled writing. The third movement is a serene

eclogue. Its Andante espressivo is most moving, as indeed is

much of this symphony. Once again those intense strings suffer from a

degree of audio spalling but their import remains clear. The vibrant Allegro vigoroso

promises victory in heroic language that has much in common with the

Harris. Its life-enhancing pizzicato recalls similar pages in Harris's

Fourth. This Diamond symphony has enjoyed a good modern recording

originally on Delos DE3093 but adopted into the Naxos family. It has also had at least one broadcast outside the USA: Gerard Schwarz conducted the BBCPO in 1990 in Manchester.

The splendidly detailed and accessibly written original programme notes for all three works can be found at the Pristine website.

Thanks to Pristine for this triumphantly successful revival of three

grand-hearted American symphonies. They are given vivid performances in

clear historic sound that captures the tragedy, up-beat excitement and

sheer valour of the times in which they were performed. I hope that

Pristine will continue quarrying this vein with other American

symphonies of the 1940s and 1950s.

Rob Barnett