This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

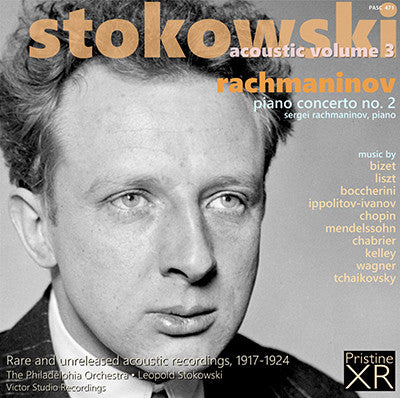

- Cover Art

Rachmaninov plays his 2nd Concert with Stokowski in truly astonishing sound quality for an acoustic recording!

"What is truly remarkable, however, is the piano sound, which is full, rich, solid, and completely stable in pitch" - Fanfare

This is the third of four volumes which aims to present all of the

surviving acoustic recordings made by Leopold Stokowski with the

Philadelphia Orchestra at the studios of the Victor recording company

between 1917 and 1924. The somewhat drawn-out nature of this project has

allowed us to track down a number of rare and unreleased sides, several

of which appear for the first time on this release.

Since

beginning the series, a number of technological advances in the field of

sound restoration have appeared, allowing each time for greater

fidelity to be extracted from the limited opportunities found in the

grooves of acoustically-recorded discs, with their highly limited

frequency and dynamic range.

One such advance is in the control

of pitch instability - the "wow and flutter" inherent to one degree or

another in all analogue recordings, and generally found to greater

degrees as recordings get older. To be able to restore solidity of pitch

to Rachmaninov's piano is to give it a degree of realism never heard

before. Despite the aforementioned technical limitations, a few moments

listening to the solo piano in the opening bars of the Piano Concerto

No. 2, not originally issued, may have you pinching yourself - surely

this is not the sound of a piano captured through a horn, cut into a

disc being driven by weights, just months before the introduction of

microphones? The delicacy of touch, the immediacy of the sound, the

solidity and (relative!) realism of the piano's tone is quite remarkable

to hear.

For many, the performance given by Rachmaninov and

Stokowski here was preferable to their 1929 electrical remake. Here we

take a step closer to that performance, alongside a panoply of single

sides and previously unissued Wagner, Tchaikovsky and one Edgar Stillman

Kelley, a composer who was new to me. My sincere thanks to all who make

this release possible. A fourth and final volume in the series will

follow within a month.

Andrew Rose

Sergei RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

1-3. Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 [30:38]

rec. January 3 and December 22, 1924

Sergei Rachmaninov, piano

1st mvt: Unissued, matrices: C-31395-2, C-31395-2, B-31397-1

2nd mvt: Victor 89166-68, matrices: C-29233-4, C-29234-3, C-29235-4

3rd mvt: Victor 89169-71, matrices: C-29236-3, C-29251-2, C-29252-2

Georges BIZET (1838-1875)

4. Carmen – Prelude [2:13]

rec. May 8, 1919, matrix: Victor B-22812-4

Victor 64822,

5. Carmen - Changing of the Guard transc. Stokowski [3:35]

rec. April 30, 1923

Victor 66263, matrix: B-27903-2

6. Carmen - March of the Smugglers transc. Stokowski [3:32]

rec. April 30, 1923

Victor 66264, matrix: B-27902-1

7. L'Arlésienne - Spanish Dance [1:40]

rec. January 28, 1922

Victor 1113, matrix: B-25942-5

Franz LISZT (1811-1886)

8. Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 orch. Karl Müller-Berghaus [3:59]

rec. May 20, 1920

Victor 74647, matrix: C-24126-4

Luigi BOCCHERINI (1743-1805)

9. Quintet in E, Op. 11, No. 5 - Minuet transc. Stokowski [2:36]

rec. January 28, 1921

Victor 66058, matrix: B-25943-4

Mikhail IPPOLITOV-IVANOV (1859-1935)

10. Caucasian Sketches Suite No. 1 - Procession of the Sardar [3:20]

rec. April 29, 1922

Victor 66106, matrix: B-26442-2

Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810-1849)

11. Prelude no 4 in E minor, Op. 28, No. 4 transc. Stokowski [2:15]

rec. November 6, 1922

Victor 1111, matrix: B-26408-7

Felix MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847)

12. A Midsummer Night's Dream - Scherzo [4:30]

rec. November 8, 1917

Victor 74560, matrix: Victor C-21056-4

Christoph Willibald von GLUCK (1714-1787)

13. Orfeo ed Euridice - Dance of the Blessed Spirits [4:43]

rec. November 8, 1917

Victor 74567, matrix: Victor C-21066-1

Emmanuel CHABRIER (1841-1894)

14. España Rhapsody [4:28]

rec. May 9, 1919

Victor 74621, matrix: Victor C-22809-7

Edgar Stillman KELLEY (1857-1944)

15. Alice in Wonderland - Suite: The Red Queen's Banquet [4:36]

rec. December 31, 1924*

Unissued, Matrix No. C-31625-1

Richard WAGNER (1813-1883)

16. Tannhäuser - Act II: Festmarsch (Entrance of the Guests) transc. Stokowski [3:08]

rec. April 30, 1923*

Unissued, Matrix No. C-27900-4

Pyotr Ilyich TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

17. Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 - Scherzo - Part 2 [4:27]

rec. December 4, 1917*

Unissued, Matrix No. C-21230-2

Recorded at Camden Church Studio (Victor Building no 22) Camden NJ, USA

except tracks 12, 13, 17:

Victor Office Building no 2, Eighteenth Floor Auditorium, Camden, NJ, USA

*Previously unissued

Leopold Stokowski, conductor

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Reviews: MusicWeb International & Fanfare

The metrical freedoms taken by the soloist-composer are a touch freer than in his remake, making this recording that much more uplifting and combustible ... a memorable achievement and it has been very well transferred here

This is the third of a projected four volumes in Pristine’s series devoted to acoustic recordings made for the Victor Company by Leopold Stokowski and members of the Philadelphia Orchestra between 1917 and 1924. I have long been skeptical about the value of orchestral recordings made with the acoustic process, prior to the introduction of the microphone in 1926. As anyone at all familiar with this primitive recording method would be aware, what is performing in these selections is not actually the Philadelphia Orchestra but rather a few of its members, clustered around a recording horn. Accordingly, a major issue in assessing this release is whether the sonic wizardry of Andrew Rose has been able to create the illusion of an actual orchestra playing in these recordings. The answer is “not entirely,” but the sound on this Pristine release is often substantially better than I would have expected, and there are portions where it is possible to overlook the absence of a full orchestra.

In the 1924 recording of the Rachmaninoff Concerto, the orchestral sound is acceptably full in tuttis, although opaque. Elsewhere, string tone is sometimes ample and sometimes thin or tubby, but the results remain thoroughly listenable. Surface noise from the source discs is audible but unobtrusive. What is truly remarkable, however, is the piano sound, which is full, rich, solid, and completely stable in pitch, although it is impossible to determine how closely this warm, rounded sound replicates the actual sound of Rachmaninoff’s playing. The sound of the Pristine remastering is in any case good enough to allow one to appreciate the performance, but the 1929 remake by the same performers remains preferable for full-orchestra sound and superior dynamic range. (I have that later recording on a 1994 RCA Gold Seal reissue, but there are other remasterings that are probably better.) Other than sound, the main difference between the two performances is the quicker main tempo for the slow movement in the earlier one. Both performances are distinguished by the composer’s effortless fluency at the piano, by a suppleness and elasticity that never strays into mannerism, and by pacing that is swifter than in most modern recordings.

Quality varies among the shorter pieces filling out the disc, but one area where Pristine’s treatment has unquestionably produced a substantial improvement is in freedom from the wow and flutter one would expect in material of this vintage. The four Bizet selections (recorded 1919–23) fare well sonically and interpretively. Bizet’s transparent orchestration is done comparatively little harm by the reduced complement of instruments, while Stokowski’s readings are lively but straightforward, without any fooling around with tempo. Liszt’s Second Hungarian Rhapsody (recorded 1920) is heavily cut, but the roughly half of it that remains is brilliantly played by the Philadelphians, and the menacing opening, with growling low strings, and the wild, headlong conclusion will impress the listener. The sharp staccato attacks at the very beginning were not employed by Stokowski in two later (complete) recordings of the piece, in 1936 and 1960–61. I don’t care much for the bloated arrangement of the Chopin Prélude or the equally soupy rendition of Gluck’s “Dance of the Blessed Spirits.” The sound in Ippolitov-Ivanov’s “Procession of the Sardar” (recorded 1922) is less good than in the Bizet and Liszt selections, and some of the wind playing seems not up to Philadelphia standards. The Midsummer Night’s Dream Scherzo (1917) suffers from a boomy, murky bass and a relatively high noise level. Chabrier’s España (1919) is heavily cut, and the sound does not much disguise the limitations of the acoustic recording process. The march from Tannhäuser (1924) is an excerpt and cuts off abruptly after three minutes. The sound is brassy and not much like a full orchestra. The excerpt from the third movement of Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique” (1917), in contrast, starts off in the middle of the movement. The balances initially seem way off, and there is some imperfect ensemble, but things improve. It is difficult to know how closely these early recordings actually represent Stokowski’s interpretations during this period and the extent to which they may have been influenced by the exigencies of the primitive recording process, but it is noteworthy that he slows the tempo at exactly the same point in this 1917 recording as in his 1945 live Hollywood Bowl performance (Memories), although tempo shifts in the earlier performance are somewhat less pronounced. The Wagner and Tchaikovsky selections and the one by the obscure American composer Edgar Stillman Kelley (1857–1944) are previously unissued.

This release demonstrates that some worthwhile listening can be drawn from the grooves of these early orchestral recordings. Rachmaninoff’s earlier recording of his Concerto No. 2 is, of course, the most valuable item on the program, in terms of historical significance and performance and sound quality, and its presence on the disc mandates a recommendation. The remaining selections will appeal primarily Stokowski completists but are worthwhile bonuses.

Daniel Morrison

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:2 (Nov/Dec 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.

Pristine Audio reminds me of a plate-spinner on the variety stage. It

has a large number of plates spinning at the moment, with multi-volume

series devoted to Beecham, Stokowski and Monteux just three that have

come my way in the past few weeks. The third volume of their series

devoted to Stokowski’s acoustic recordings (see reviews of Volume 1/a> and Volume 2)

has a major work, and then a raft of lighter material, several of which

pieces will be of considerable interest to Stokowski collectors as they

have never before been issued.

The major work is Rachmaninov’s

Second Piano Concerto with the composer as soloist. This 1924 recording

shouldn’t be confused with the later electric remake. The strange

history of its missing first movement – never issued at the time, thus

forcing purchasers to buy a torso of the work – can be explored

elsewhere, though suffice to say it first reappeared commercially in RCA

Red Seal’s Rachmaninov edition of his complete recordings. It’s known

that he played a Steinway Model B here, which was raised on a platform

to allow the horn better to pick up his sound – quite a common practice

at the time – and the results were exceptional. Given that Rachmaninov

never approved the first movement for release, listeners would have had

to start with the slow movement but for us no such impediment exists. It

is one of those little ironies of recording history that Victor was

recording a pretty complete complement of orchestral players back in

1917 but in succeeding years they actually cut back, so that by the end

of the acoustic era the Philadelphia often had around 38 or 40 players

in the studio. Any bass reinforcements in this Rachmaninov recording

have been utilised quite subtly. The metrical freedoms taken by the

soloist-composer are a touch freer than in his remake, making this

recording that much more uplifting and combustible. It is, in any case, a

memorable achievement and it has been very well transferred here.

The remainder of the programme is graced by a succession of

single-sided sweetmeats. The quartet of Bizet gives the brass and winds a

workout in particular – the March of the Smugglers is notably

well played – and whilst this is by no means the first recording of

Boccherini’s Minuet, it is assuredly one of the most suavely played.

Ippolitov-Ivanov’s Procession of the Sardar from the Caucasian Sketches Suite No.1

offers some exotic fair and Stokowski’s arrangement (and the

orchestra’s performance of Chopin’s Prelude in E minor) is persuasive:

other Stoky Chopin arrangements were not always so tasteful. The Gluck

is, alas, too bass heavy and lugubrious but the 1919 Chabrier España Rhapsody

makes up for it. The last three pieces have never before been released.

Like everything else, the sound is excellent for the 1917-24 time

period. We hear the second part of the Scherzo from Tchaikovsky’s Sixth

Symphony, and part one (only) of Tannhauser’s Festmarsch, which duly stops abruptly. But the gem here is the piece by the American composer Edgar Stillman Kelley whose The Red Queen’s Banquet, from his Alice in Wonderland

suite, offers some busy material. In fine sound, it brings Kelley to

the attention of contemporary listeners and one wonders what else is out

there by him.

Full documentation can be found on Pristine’s

website, as there isn’t much room in the disc for much beyond a brief

Producer’s Note and the running order.

Jonathan Woolf

MusicWeb International